|

VICKSBURG National Military Park |

|

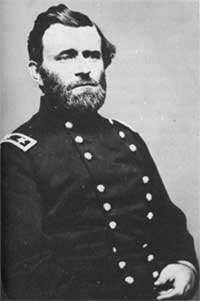

Maj. Gen. U. S. Grant, commanding the Union Army of the Tennessee. Courtesy National Archives. |

Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, commanding the Confederate Army of Vicksburg. Courtesy Flohr Studio, Vicksburg. |

The Bayou Expeditions:

Grant Moves Against Vicksburg— and Fails

By the end of January, Grant had arrived at the Union encampment at Milliken's Bend, 30 miles north of Vicksburg, and assumed leadership of the operations against Vicksburg. His army, numbering about 45,000, was divided into three corps under General Sherman, Maj. Gen. John McClernand, and Maj. Gen. James Birdseye McPherson. Cooperating with the army, and providing aid without which the bayou expeditions would not have been possible, was the Western Flotilla under Porter. This fleet consisted of 11 ironclads, 38 wooden gunboats, rams, and sundry auxiliary craft mounting over 300 guns and carrying a complement of 5,500. The war in the West now hinged upon the effectiveness of this combined land and naval force. Under Grant's direction it maneuvered over hundreds of miles of river and bayou seeking to outflank Vicksburg. The capture of the city would result not from great battles but from a war of movement.

THE GEOGRAPHICAL PROBLEM OF VICKSBURG. The capture of Vicksburg proved difficult partly because of the topography of the area, which so favored defense of the city as to render the fortress almost impregnable to attack. To move against the city it was necessary to reach the bluffs which extended north and south and on which Vicksburg had been built. Behind the bluffs, to the east, lay dry ground on which an army might maneuver; below the bluffs, on both sides of the river, flooded swamplands prevented ground movements. With his army behind the bluffs, either above or below, Grant might come to grips with Pemberton's Army of Vicksburg. Unless he reached the bluffs, capture of the city would be impossible; it could not be assaulted from the river.

The line of bluffs which marks the eastern boundary of the Mississippi Valley leaves the river at Memphis, curves in a great 250-mile arc away from the river, and then swings back to reach the river again at Vicksburg. Enclosed between the bluffs and the river is the "Delta"—a strip of land averaging some 60 miles in width, which is now a fertile, well-drained, cotton-growing region. In 1863, it was a swampy bottom land containing numerous rivers and bayous, subject to incessant floods. It was covered with thick forests and dense undergrowth, a condition, which, according to Grant's engineer officer, "renders the country almost impassable in summer, and entirely so, except by boats, in winter." This impenetrable swampland, lying before the bluffs, effectively guarded Vicksburg's right flank. Unless the waterways of the Delta might provide a passage to the bluffs, operations against Vicksburg to the north were hopeless.

Pivot-gun and crew of the Union warship

Wissahickon, which fought the Vicksburg batteries.

From Photographic History of the Civil War.

South of Vicksburg the prospect for the Union Army was equally dismal. After meeting the river at Vicksburg, the bluffs follow the river course closely to the south and were accessible, therefore, to troops from the Mississippi River. But the river batteries of the city prevented passage of transports to the river below; for troops to get below the city it was necessary to move through the Louisiana lowlands west of the river. This region was like the Delta north of Vicksburg—flooded bottom lands interspersed with bayous, rivers, and lakes. It would prove equally obstinate to land movements.

To increase Grant's difficulties, his campaign against Vicksburg was begun during the wet season when streams were overflowing and lowlands impassable. The winter of 1862—63 was a period of unusually high water, the Mississippi cresting higher than its natural banks from December until April. Had Grant reached Vicksburg during the dry season, his problem would have been less formidable.

Until the bottoms were dry enough to permit land movements, the Union commander felt himself compelled to keep the army active. Even if success along the water routes seemed unlikely, he reasoned that prolonged idleness would be injurious to the health and morale of his troops. Grant had come to believe that military success was won by the aggressive. To Grant's critics, who demanded that he open the Mississippi without delay or be replaced by someone who could, Lincoln replied, "I can't spare this man; he fights."

As Pemberton prepared to defend Vicksburg he was beset by difficulties rivaling those of his opponent, despite the topography which was friendly to his defensive purpose. Vicksburg would be secure only so long as the Confederate Army could prevent Grant from achieving a foothold on the high ground above or below the city. Yet, to prevent such a lodgment, it was necessary for Pemberton to defend a wide front extending 200 miles above and below Vicksburg, at any point along which Grant might strike. To cover this large area the Confederate commander would have to disperse his limited garrison dangerously and at the same time retain sufficient troops to protect the city—his primary responsibility. Under such conditions it was essential for Pemberton to receive information of Federal movements in order to concentrate his troops rapidly to meet the advance. Yet Pemberton was almost wholly lacking in cavalry and had no navy to interfere with and report Union progress through the rivers and bayous. Both Pemberton and Grant faced exacting problems in command during the Vicksburg operations.

|

| History | Links to the Past | National Park Service | Search | Contact |

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |