|

Geological Survey 18th Annual Report (Part II)

Glaciers of Mount Rainier Rocks of Mount Rainier |

NARRATIVE.

The reconnaissance during which the notes for this essay were obtained began at Carbonado, a small coal-mining town about 20 miles southeast of Tacoma, with which it is connected by a branch of the Union Pacific Railroad. Carbonado is situated on the border of the unbroken forest. Eastward to beyond the crest of the Cascade Mountains is a primeval forest, the density and magnificence of which it is impossible adequately to describe to one who is not somewhat familiar with the Puget Sound region. From Carbonado a trail, cut through the forest under the direction of Willis in 1881, leads to Carbon River, a stream flowing from Mount Rainier, which it formerly crossed by a bridge that is now destroyed, and thence continues to the west of the mountain to Busywild. A branch of this trail leads eastward to the north side of the mountain, making accessible a beautiful region near the timber line, known as Spray Park. A portion of the main trail and the branch leading to Spray Park is shown on the accompanying map, Pl. LXVI.

|

| Pl. LXVI. MAP OF THE GLACIER SYSTEM, MOUNT RAINIER, WASHINGTON. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Our party consisted of Bailey Willis, geologist in charge, George Otis Smith and myself, assistants, and F. H. Ainsworth, Fred Koch, William B. Williams, and Michael Autier, camp hands.

IN THE FOREST.

From Carbonado we proceeded with pack animals along the Willis trail, already mentioned, to the crossing of Carbon River. We then left the main trail and went up the right bank of the river by a trail recently cut as far as the mouth of Chenuis Creek. At that locality our party was divided. Willis and myself, taking blankets, rations, etc., and crossing the river, proceeded up its bowlder-strewn left bank to the foot of Carbon Glacier. The remainder of the party cut a trail along the right bank, and in the course of a few days succeeded in making a depot of supplies near where the river emerges from beneath the extremity of the glacier. The pack train was then taken back to near Carbonado for pasture.

The tramp from Carbonado to the foot of the Carbon Glacier was full of interest, as it revealed the characteristics of a great region, covered within a dense forest, which is a part of the deeply dissected Tertiary peneplain surrounding Mount Rainier. The rocks from Carbonado to Carbon River crossing are coal bearing. Extensive mines are worked at Carbonado, and test shafts have been opened at a few localities near the trail which we followed. At Carbonado the river flows through a steep-sided canyon about 300 feet deep. Near where the Willis trail crosses the stream the canyon broadens, is deeply filled with bowlders, and is bordered by forest-covered mountains fully 3,000 feet in elevation. On account of the dense forests, the scenery throughout the region traversed is wild and picturesque. At a few localities glimpses were obtained of the great snow-clad dome of Mount Rainier, rising far over the intervening tree covered foothills.

The forests of the Puget Sound region are the most magnificent on the continent. The moist atmosphere and genial climate have led to a wonderfully luxuriant growth, especially of evergreens. Huge fir trees and cedars stand in close-set ranks and shoot upward straight and massive to heights which frequently exceed 250 feet, and sometimes are even in excess of 300 feet. The trees are frequently 10 to 12 feet or more in diameter at the height of one's head and rise in massive columns without a blemish to the first branches, which are in many instances 150 feet from the ground. The soil beneath the mighty trees is deeply covered with mosses of many harmonious tints, and decked with rank ferns, whose gracefully bending fronds attain a length of 6 to 8 feet. Lithe, slender maples, termed vine-maples from their habit of growth, are plentiful, especially along the small water courses. In many places the broad leaves of the devil's club (Patsia horrida) give an almost tropical luxuriance to the shadowy realm beneath the lofty canopies formed by the firs and cedars.

In writing of life in this forest while prospecting for coal in 1881, Willis1 states that one of the fir trees which was measured rose like a huge obelisk to a height of 180 feet without a limb and tapered to a point 40 feet above. "The more slender trees, curiously enough, are the taller, straight, clear shafts rise 100 to 150 feet, topped with foliage whose highest needles would look down on Trinity spire. Cedars, hemlocks, spruce, and white firs mingle with these giants, and not competing with them in height, they fill the spaces in the vast colonnade. * * * The silence of these forests is awesome, the solitude oppressive. The deer, the bear, the panther, are seldom met; they see and hear first and silently slip away, leaving only their tracks to prove their numbers. There are very few birds. * * * The wind plays in the tree tops far overhead, but seldom stirs the branches of the smaller growth. The great tree trunks stand immovable. The more awful is it when a gale roars through the timber, when the huge columns sway in unison and groan with voices strangely human."

1Bailey Willis, Canons and glaciers, a journey to the ice fields of Mount Tacoma The Northwest, April, 1883, Vol. I, p. 2.

The mighty forest through which we traveled from Carbonado to the crossing of Carbon River extends over the country all about Mount Rainier and clothes the sides of the mountain to a height of about 6,000 feet. From distant points of view it appears as all unbroken emerald setting for the gleaming, jewel-like summit of the snow-covered peak.

In spite of the many attractions of the forest, it was with a sense of relief that we entered the canyon of Carbon River and had space to see about us. The river presents features of geographical interest, especially in the fact that it is filling in its valley. The load of stone contributed by the glaciers, from which the stream comes as a roaring turbid flood, is greater than it can sweep along, and much of its freight is dropped by the way. The bottom of the canyon is a desolate, flood-swept area of rounded bowlders, from 100 to 200 yards broad. The stream channel is continually shifting, and is frequently divided by islands of bowlders, heaped high during some period of flood. Many of the stream channels leading away from Mount Rainier are known to have the characteristics of the one we ascended and show that the canyons were carved under different conditions from those now prevailing. The principal amount of canyon cutting must have been done before the streams were overloaded with débris contributed by glaciers—that is, the deep dissection of the lower slope of Mount Rainier and of the platform on which it stands must have preceded the Glacial epoch.

ON THE GLACIERS.

After a night's rest in the shelter of the forest, lulled to sleep by the roar of Carbon River in its tumultuous course after its escape from the ice caverns, we climbed the heavily moraine-covered extremity of Carbon Glacier. At night, weary with carrying heavy packs over the chaos of stones that cover the glaciers, we slept on a couch of moss beautified with lovely blossoms, almost within the spray of Philo Falls, a cataract of clear icy water that pours into the canyon of Carbon Glacier from snow fields high up on the western wall of the canyon.

I will ask the reader to defer the study of the glaciers until we have made a reconnaissance of the mountain and climbed to its summit, as he will then be better prepared to understand the relation of the glaciers, névés, and other features with which it will be necessary to deal. In this portion of our fireside explorations let us enjoy a summer outing, deferring until later the more serious task of questioning the glaciers.

From Philo Falls we ascended still higher, by following partially snow-filled lanes between the long lateral moraines that have been left by the shrinking of Carbon Glacier, and found three parallel, sharp crested ridges about a mile long and from 100 to 150 feet high, made of bowlders and stones of all shapes, which record the former positions of the glacier. Along the western border of the oldest and most westerly of these ridges there is a valley, perhaps 100 yards wide, intervening between the abandoned lateral moraine and the western side of the valley, which rises in precipices to forest-covered heights at least 1,000 feet above. Between the morainal ridges there are similar narrow valleys, each of which at the time of our visit, July 15, was deeply snow-covered. The ridges are clothed with spruce and cedar trees, together with a variety of shrubs and flowering annuals. The knolls rising through the snow are gorgeous with flowers. A wealth of purple Bryanthus, resembling purple heather, and of its constant companion, if not near relative, the Cassiope, with white, waxy bells, closely simulating the white heather, make glorious the mossy banks from which the lingering snow has but just departed. Acres of meadow land, still soft with snow water and musical with rills and brooks flowing in uncertain courses over the deep, rich turf, and beautiful with lilies, which seemed woven in a cloth of gold about the borders of the lingering snow banks. We are near the upper limit of timber growth, where parklike openings, with thickets of evergreens, give a special charm to the mountain side. The morainal ridge nearest the glacier is forest-covered on its outer slope, while the descent to the glacier is a rough, desolate bank of stones and dirt. The glacier has evidently but recently shrunk away from this ridge, which was formed along its border by stones brought from a bold cliff that rises sheer from the ice a mile upstream. Standing on the morainal ridge overlooking the glacier, one has to the eastward an unobstructed view of the desolate and mostly stone and dirt covered ice. Across the glacier another embankment can be seen, similar to the one on the west, and, like it, recording a recent lowering of the surface of the glacier of about 150 feet. Beyond the glacier are extremely bold and rugged mountains, scantily clothed with forests nearly to their summits. The position of the timber line shows that the bare peaks above are between 8,000 and 9,000 feet high. Looking southward, up the glacier, we have a glimpse into the wild amphitheater in which it has its source. The walls of the great hollow in the mountain side rise in seemingly vertical precipices about 4,000 feet high. Far above is a shining, snow-covered peak, which Willis named the Liberty Cap. It is one of the culminating points of Mount Rainier, but not the actual summit. Its elevation is about 14,300 feet above the sea. Toward the west the view is limited by the forest-covered morainal ridges near at hand and by the precipitous slopes beyond, which lead to a northward-projecting spur of Mount Rainier, known as the Mother Mountains. This, our first view of Mount Rainier near at hand, has shown that the valley down which Carbon Glacier flows, as well as the vast amphitheater in which it has its source, is sunk in the flanks of the mountain. To restore the northern slope of the ancient volcano as it existed when the mountain was young we should have to fill the depression in which the glacier lies at least to the height of its bordering ridges. On looking down the glacier we see it descending into a vast gulf bordered by steep mountains, which rise at least 3,000 feet above its bottom. This is the canyon through which the water formed by the melting of the glacier escapes. To restore the mountain this great gulf would also have to be filled. Clearly the traveler in this region is surrounded by the records of mighty changes. Not only does he inquire how the volcanic mountain was formed, but how it is being destroyed. The study of the glaciers will do much toward making clear the manner in which the once smooth slopes have been trenched by radiating valleys, leaving mountain-like ridges between.

Another line of inquiry which we shall find of interest as we advance is suggested by the recent shrinkage of Carbon Glacier. Are all of the glaciers that flow from the mountain wasting away? If we find this to be the case, what climatic changes does it indicate?

TO CRATER LAKE.

From our camp among the morainal ridges by the side of Carbon Glacier we made several side trips, each of which was crowded with observations of interest. One of these excursions, made by Mr. Smith and myself, was up the snow fields near camp; past the prominnent outstanding pinnacles known as the Guardian Rocks, one red and the other black; and through Spray Park, with its thousands of groves of spire-like evergreens, with flower-enameled glades between. On the bare, rocky shoulder of the mountain, where the trees now grow, we found the unmistakable grooves and striations left by former glaciers. The lines engraved in the rock lead away from the mountain, showing that even the boldest ridges were formerly ice covered. Our route took us around the head of the deep canyon through which flows Cataract Creek. In making this circuit we followed a rugged saw-tooth crest, and had some interesting rock climbing. Finally, the sharp divide between Cataract Creek and a small stream flowing westward to Crater Lake was reached, and a slide on a steep snow slope took us quickly down to where the flowers made a border of purple and gold about the margins of the snow. Soon we were in the forest, and gaining a rocky ledge among the trees, could look down on Crater Lake, deeply sunk in shaggy mountains which still preserve all of their primitive freshness and beauty. Snow lay in deep drifts beneath the shelter of the forest, and the lake was ice covered except for a few feet near the margin. This was on July 20. I have been informed that the lake is usually free of ice before this date, but the winter preceding our visit was of more than usual severity, the snowfall being heavy, and the coming of summer was therefore much delayed.

The name Crater Lake implies that its waters occupy a volcanic crater. Willis states that Nature has here placed an emerald seal on one of Pluto's sally ports; but that the great depression now water-filled is a volcanic crater is not so apparent as we might expect. The basin is in volcanic rock, but none of the characteristics of a crater due to volcanic explosions can be recognized. The rocks so far as I saw them, are massive lavas, and not fragmental scoriae or other products of explosive eruptions. On the bold, rounded rock hedges down which we climbed in order to reach the shore, there were deep glacial scorings, showing that the basin was once deeply filled with moving ice. My observations were not sufficiently extended to enable me to form an opinion as to the origin of the remarkable depression, but whatever may have been its earlier history, it has certainly been profoundly modified by ice erosion.

Following the lake shore southward, groping our way beneath the thick, drooping branches which dip in the lake, we reached the notch in the rim of the basin through which the waters escape and start on their journey to Mowich River and thence to the sea. We there found the branch of the Willis trail leading to Spray Park, and turned toward camp. Again we enjoyed the luxury of following a winding pathway through silent colonnades formed by the moss grown trunks of noble trees. On either side of the trail worn in the brown soil the ferns and flowering shrubs were bent over in graceful curves, and at times filled the little-used lane, first traversed fifteen years before.

The trail led us to Eagle Cliff, a bold, rocky promontory rising as does El Capitan from the Yosemite, 1,800 feet from the forest-lined canyon of Mowich River. From Eagle Cliff one beholds the most magnificent view that is to be had in all the wonderful region about Mount Rainier. The scene beheld on looking eastward toward the mighty mountain is remarkable alike for its magnificence and for the artistic grouping of the various features of the sublime picture. In the vast depths at one's feet the tree tops, through which the mists from neighboring cataracts are drifting, impart a somber tone and make the valley's bottom seem far more remote than it is. The sides of the canyon are formed by prominent serrate ridges, leading upward to the shining snow fields of the mighty dome that heads the valley. Nine thousand feet above our station rose the pure white Liberty Cap, the crowning glory of the mountain as seen from the northward. The snow descending the northwest side of the great central dome is gathered between the ridges forming the sides of the valley and forms a white névé from which flows Willis Glacier. Some idea of the grandeur of this scene may be gained from the illustration, Pl. LXVIII. In looking up the valley from Eagle Cliff the entire extent of the snow fields and of the river like stream of ice flowing from them is in full view. The ice ends in a dirt-covered and rock-strewn terminus, just above a huge rounded dome that rises in its path. In 1881 the ice reached nearly to the top of the dome and broke off in an ice cliff the detached blocks falling into the gulf below. Tine appearance of this cliff in 1885 is shown by Pl. LXXXI. The glacier has now withdrawn its terminus well above the precipice where it formerly fell as an ice cascade, and its surface has shrunk away from well-defined moraines in much the same manner as has already been noted in the case of Carbon Glacier. A more detailed account of the retreat of the extremity of Willis Glacier will be given later.

|

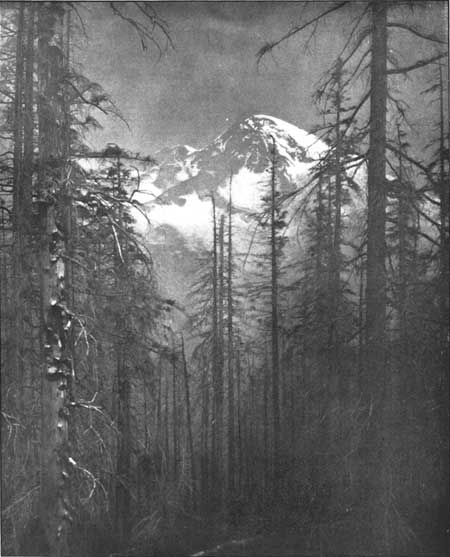

| Pl. LXVII. SCENE IN THE FOREST SOUTH OF MOUNT RAINIER. |

From Eagle Cliff we continued our tramp eastward along the trail leading to Spray Park, climbed the zigzag pathway up the face of a cliff in front of Spray Falls, and gained the picturesque and beautiful park-hike region above. An hour's tramp brought us again near the Guardian Rocks. A swift descent down the even snow fields enabled us to reach camp just as the shadows of evening were gathering in the deeper canyons, leaving the silent snow fields above all aglow with reflected sunset tints.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

rpt/18-2/sec1-5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Mar-2006