|

El Malpais

In the Land of Frozen Fires: A History of Occupation in El Malpais Country |

|

Chapter V:

A GARRISON IN THE MALPAIS: THE FORT WINGATE STORY (continued)

The post's new commander, Lt. Col. José Francisco Chávez, assumed command of four companies of the lst New Mexico Volunteers, Companies B, C. E. and F. [17] The majority of the officers and enlisted personnel were of Hispanic origin. With an obvious ethnocentric viewpoint, General Canby had issued orders to keep the companies in his department segregated with the exception of the New Mexico units. In the New Mexico companies, Canby required at least one officer and a quarter of the non-commissioned staff to be bilingual. [18] The appointment of Chavez to command at Wingate was indeed fortuitous. He ranked as one of New Mexico's favorite sons and was stepson to Governor Henry Connelly. Born in Bernallilo County in 1833, Chavez attended schools at St. Louis University and later spent two years at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City. Prior to the Civil War he engaged in expanding the sheep industry. A staunch Unionist, he joined the 1st New Mexico Volunteers with the rank of major. When Ceran St. Vrain resigned as colonel of the 1st New Mexico, Christopher Carson became the regiment's colonel and Chavez elevated to the lieutenant colonelcy slot. [19]

In constructing the perimeter of the post, approved designs dictated the fort's dissection at right angles and along the cardinal points for added protection against attacks. A large open space was reserved between officer's quarters and company quarters forming an imposing parade ground. Sycamore trees were planted around the edge of the parade ground offering a shaded and symmetrically pleasing atmosphere to the company street. [20]

Chavez's first order of business at Fort Wingate, per instructions from General Carleton was the preparation of shelter for the sick followed in priority order by the construction of buildings to house stores, animals, and then the men. [21] Although construction progressed at a furious pace, the post would never be fully completed due to incessant demands for scouting missions against Navajos and the fort's poor site. Built on top of a swampy plain with groundwater only two feet below the surface, the fort had major structural problems. The alkaline water extracted a heavy toll on the adobe walls reducing them in short order to a spongy, decaying mess. Officers complained that they spent more time repairing the structures than they did building them. [22] Because of the urgency for shelter, most of the buildings were built in quick and shoddy fashion. Many structures were substandard or never finished. As late as 1864 the post hospital, officers quarters, and guardhouse were incomplete. The quartermaster storehouse had a dirt floor. Enlisted men were still being sheltered in tents, which habitually fell down in heavy winds. [23]

The indefatigable Col. Chavez devoted energy and time to constructing shelter, a task made difficult with the onset of winter only weeks away. On November 7, he wrote Capt. Ben Cutler, Assistant Adjutant General in Santa Fe, that a garrison work detail had nearly completed a 2,000-yard irrigation ditch connecting Fort Wingate to the springs at Ojo del Gallo. Other soldiers, Chavez wrote, were dispatched to the nearby Zuni Mountains to fell timber for use in erecting storehouses and corrals. As a footnote Chavez added, "but I am afraid that we will not be able to have everything under shelter before cold weather on account of the small amount of transportation now at this post." [24]

Chavez's fears were no exaggeration. Capt. Julius C. Shaw described Wingate in a letter of December 1862 that was printed in the March 13, 1863, San Francisco Alta California: "The fort looks vastly fine on paper, but as yet it has no other existence. The garrison consists of four companies of my regiment--The Fourth New Mexico Mounted Rifles--and we live on, or rather exist, in holes or excavations, made in the earth, over which our cloth tents are pitched. We are supplied also with fire places, chimneys, etc., and on the whole, during the beautiful pleasant weather of the past few weeks, have enjoyed ourselves quite well. Our camp presents more appearance of a gypsy encampment than anything else I can compare it to." [25]

To expedite construction, Chavez sent fatigue parties to cannibalize razed Fort Lyon and retrieve all salvageable materials. Unlike most western frontier military forts, which never built wooden stockades to surround the post, Fort Wingate did. Plans called for a stockade 4,340 feet long and 8 feet high. [26] More than one million feet of lumber went into its construction. In addition to the timber, 9, 317 feet of adobe walls, one foot thick and eight feet high were required. [27] Lieutenant Allen L. Anderson, 5th Infantry and Acting Engineer Officer, commented that $45,000 in appropriations would be required to construct the post, a cost figure approved by Washington. [28] While Col. Chavez hastened to build the post, he did not ignore his objective--the Navajos. In an effort to differentiate friendly Navajos from those disposed to be unfriendly to the government, Chavez sent notices inviting the Indians to Fort Wingate. It came to no one's surprise that few accepted his invitation. [29]

Meanwhile, General Carleton set into motion his Indian relocation plan for the Navajos and Mescalero Apaches. The Bosque Redondo at Fort Sumner became the designated collecting point and permanent home for both tribes. "The purpose I have in view," wrote Carleton, "is to send all captured Navajos and Apaches to that point [Bosque Redondo], and there to feed and take care of them until they have opened farms and became able to support themselves, as the Pueblo Indians of New Mexico are doing. Removal should be the "sine qua non" of peace." [30]

By the fall of 1862, Navajos began to reflect concern with the military buildup at Fort Wingate. A Navajo delegation journeyed to Santa Fe in December to discuss a peace proposal. A stern Carleton informed the 18 assembled Indians, including war chiefs Delgadito and Barboncito, that "they could have no peace until they would give other guarantees than their word that the peace should be kept." [31] Unless the Navajos accepted peace on unconditional terms of the U.S. Government, a war of attrition was eminent. The Navajos were noncommittal but not intimidated by white man's talk.

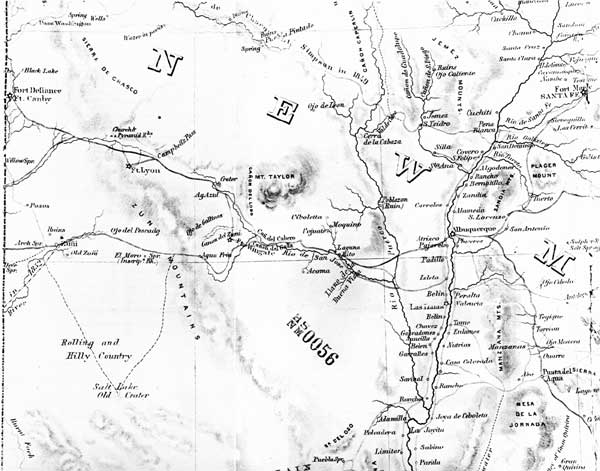

Figure 1. Fort Wingate Environs taken from territorial map of New Mexico, 1867.

Courtesy Museum of New Mexico, Neg. No. 142599.

(click on map for a larger image)

While Carleton warned the Navajos of their impending fate, Col. Chavez stockpiled mountains of supplied at Fort Wingate for a spring campaign. In February 1863, Chavez and the New Mexico Volunteers underwent their baptism of fire against the Navajos. An undetermined number of Navajos disrupted mundane post routines when they breached the corral and stole four horses. A punitive expedition sent after the perpetrators failed to apprehend the horse thieves. [32] Occurring at the same time as the horse raid, Indians ambushed and killed four Mexicans and one friendly Navajo on the Cebolleta and Cubero road east of Fort Wingate. The assailants escaped.

The ill-tempered Carleton fumed at Chavez's report that outlined the horse stealing sortie. Carleton fired a stinging reprimand to Chavez ordering him to seize 20 men and their families, and hold them for hostages until the horses were returned. He finished his missive with, "what Col Chavez does he must with a strong firm hand. Child's play with the Navajo must stop henceforth." [33]

In April General Carleton inspected Fort Wingate. He divulged to Chavez his plans for the ultimate fate of the Navajos. Peaceful factions would be transferred to Bosque Redondo. Truculent parties would be hunted down and killed if they resisted removal. About May 1 at the village of Cubero, Carleton and Lt. Col. Chavez again conferred with Navajo statesmen willing to listen to the white men. Indian dignitaries included Degadito and Barboncito. Carleton explained the options to the attentive warriors. It was not what they wanted to hear. Barboncito denounced the proposal, declaring he would neither go to eastern New Mexico nor fight. Writing on the episode, Col. Chavez quipped, "When it comes to the pinch he will fight run or go to Bosque Redondo." [34]

To combat the Navajos, Chavez mustered less than 300 soldiers with only one mounted company. [35] As spring turned to summer, Indian harassments near the malpais post escalated. On June 24, Navajos repeated their penetration of the horse corral, this time absconding with three head of oxen and driving off some horses. Chavez directed Capt. Chacón to recover the stolen stock and punish the marauders. Chacón with twenty-two men tracked the offenders up the old Fort Defiance Road. On the 28th he overtook the rear of the Navajos. Mounting a charge, the New Mexico Volunteers scattered the surprised warriors and recaptured four horses and a mule. [36]

While Fort Wingate troops parried with the Navajos, General Carleton declared himself ready to take the fight to the Navajos. And the General meant business. Messages were transmitted to Fort Wingate, informing Col. Chavez to reopen communications with the Navajos. Carleton admonished his subordinate to instruct the chiefs they had until July 20 to surrender or face dire military consequences. [37] On July 7, Barboncito, Delgadito, and Sarracino conferred with Chavez. The colonel acquainted the chiefs with the ultimatum. Barboncito, the spokesperson, appealed to Chavez that the chiefs desired peace but did not wish to move to Bosque Redondo. The meeting expired with the chiefs remaining non-committal concerning surrender or removal.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

elma/history/hist5a.htm

Last Updated: 10-Apr-2001