|

Denali

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER 4:

THE KANTISHNA AND NEARBY MINING DISTRICTS

When Karstens and the others came down from the mountain, they headed for Eureka, the mining camp at the junction of Eureka and Moose creeks, now known as Kantishna. There a miner named Hamilton fed them "like a Prince." Next day, they reached Joe and Fanny Quigley's place, where they enjoyed a "big feed." And the next day they had another big feed at Glacier City. [1]

|

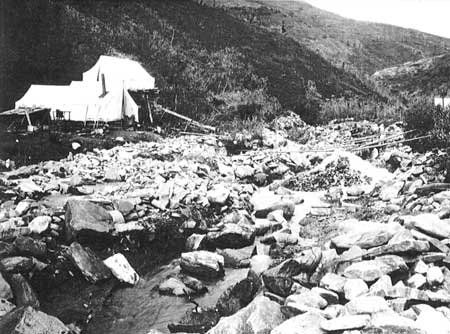

| Claim No. 2a on Eureka, Kanishna area, 1906. L.M. Prindle Collection, USGS |

Who were these miners, these dwellers of the far places for whom hospitality was code and communion? All the early travelers remarked of the miners that they were a special breed, men and women of everlasting hope. Failure they knew well. For gold was elusive: scattered in the gravels of rushing streams, clinched in rocky crevices, hidden under deep, sometimes hundreds-of-feet deep, sediments that overlay ancient watercourses. These were all variations of placer gold—gold already eroded from the country rock and concentrated here and there (but where?) by Nature's running waters. This kind of gold, when discovered, ran out fast in those early days, for much of the gold escaped the ingenious but crude traps set by the pioneer miners. All of them then used flows and charges of water—as Nature had already done, to a point—to move lighter rock and gravel, allowing the heavy gold to settle in the riffles of sluice boxes.

|

| Sluice boxes, Spruce Creek, Kantishna area, 1906. L.M. Prindle Collection, USGS |

Stampedes brought mixed company, in waves. And the mining proceeded in stages. Some prospectors following, in Robert Dunn's phrase, "the old, relentless dream-trail," [2] found paying colors. The word got out. First to the new Eldorado were prospectors and miners already in the country. Expert and efficient, they found and staked the better claims. The second wave of stampeders, often delayed until the next season, staked what was left or found work as laborers at the operating mines. Many of these latecomers lacked experience. Theirs, typically, was a life of leavings, pittance-pay hard labor (given mining-camp prices), and eventual return to more civilized precincts.

As surface-stream gold gave out, and if the geology were right, placer operations shifted to bench claims and deep-hole mining—probing old creek terraces or the ancestral streambeds far below. In the first primitive efforts, the miners melted through the frozen dirt with hot rocks or wood fires; later they used steam, generated by small, wood-fired boilers. They dug their shafts to bedrock where the old streams had concentrated the gold. By this time only hard-core miners remained, for intensive development work, often taking years, preceded any hope of pay, once the "sunburnt" gold was gone.

|

| Bench mining on Glacier Creek, 1906. L.M. Prindle Collection, USGS |

If the arduous bench and deep-hole efforts failed to fill their pokes, the miners began looking up the steep creeks toward the domes and ridges where the lode gold—the uneroded gold of creation—lay hidden in the solid rock. Then hard-rock mining began with dynamite and pick and pry-bar—into the very heart of the mountain, where veins of gold-bearing quartzite meandered through the fissures and fractures of geologic history. Kantishna went fairly quickly from placer mining to lode prospecting. As improved placer techniques allowed, miners made their pay from placer benches and deep holes (and from reworking previously sifted surface-stream gravels) while they prospected and developed the lode claims.

|

| Placer miners in the Kantishna area, 1919. L.M. Prindle Collection, USGS |

Because all the Denali-region districts were remote and their pay locations spotty—without the vast extent of the Klondike, Fairbanks, and Nome fields—there was little corporate takeover and agglomeration of the mines as compared to the climax stage in those larger fields. Thus, continuity of people and ownership persisted clear into the Thirties in some places. This was particularly true in the Kantishna. The mining camps scattered on the streams and ridges comprised a loose-knit community. Rugged topography—deep valleys and tortuous ridges—hindered casual visiting. But when someone did drop by on the way out to town, or back in, it was a special occasion. And being far from town, helpfulness—really going out of one's way—was not marked up as a debt owed, for tomorrow or next year, it might be yourself who needed the gathering-round of neighbors.

The principal gold fields of the Denali region include:

The Kantishna district with most of the mining concentrated in the southwest part of the Kantishna Hills, just north of Wonder Lake.

The Bonnifield district to the northeast, tapping tributaries of the Tanana flowing north from the Alaska range.

And the fields to the south of the range in the Susitna drainage—the hand-work and dredge placers on Cache and Peters creeks, draining the Dutch and Peters Hills; the upper Chulitna River lode mines; and the surface and deep-hole placers of the Valdez Creek area on the upper Susitna, east of Cantwell.

All of these were remote fields, far removed from the big rivers that permitted easy steamboat transport of supplies and equipment to landings near mine sites. The Valdez Creek miners relied at first on overland transport from the military wagon road between Valdez and Eagle. (Later, when the Alaska Railroad reached Cantwell, they shifted their base of supply to that town.) The other districts used a combination of river and overland transport. Small steamers chugged up the tributaries as far as they could go. At the heads of navigation of these shoaling streams a "last chance" trading station might be established. From such stations goods went farther upstream in launches, poling boats, and horse-drawn scows. Finally, overland travel with dogsleds or horse-drawn sledges brought the goods to the mines. Each link in the transportation system cost money. Barring very rich diggings, the big financiers showed only passing interest in such fields. There was no profit after a big investment, as the era of company mining (1917-21) at Valdez Creek showed. [3] Thus the small-scale, labor-intensive mining of the pioneer field tended to persist in such places. Where stripped-down hydraulic and dredging and hard-rock operations did occur on the upper creeks, they were plagued by water shortages and equipment-maintenance problems. Improvisation and creative salvage and adaptation of any machined metal helped the miners to limp along. [4]

With construction of the Alaska Railroad (1915-23)—up the Susitna Valley through Broad Pass, and south from Fairbanks along the Nenana—leading to spur roads and trails from the rail line, transportation improved. But by then exhaustion of surface placers, and less-than-Bonanza prospects for more expensive mining, had reduced many of the camps to subsistence levels. With few exceptions up through the Thirties, large-scale mining enterprises in these districts could not be made to pay. Typically, after two or three seasons of expense and labor to develop and put into operation such enterprises, they folded and the engineers left. Then the durable old timers with modest expectations salvaged machinery, pipes, and other useful items from the abandoned company camps.

All of these districts started up about the same time, in the years 1903 to 1907. [5] Through the Thirties they had similar sequences of boom and bust, then revival with modest investments of outside money, usually followed by disappointment. They all responded with flurries when the railroad came near and when, in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt raised the price of gold to $35 an ounce.

Mines in these districts produced by-products (or in a few instances were primary producers) of other metals: silver, zinc, lead, antimony, or copper. But gold would always be the main lure and bring in all but a small fraction of the pay.

In the early days, coal—which would soon become Alaska's second most valuable mineral—was only of local consequence in the Denali region. Small outcrops and shallow beds occurred in many places, and if one of them was near a mining camp it could be exploited as fuel for domestic and forge and machinery operations. For example, the Dunkle Mine on the south side supplied the nearby Golden Zone mine overlooking the Chulitna's West Fork, until the miners shifted to hydropower. Vast coal deposits—untappable without bulk transport—occupied the Matanuska and Nenana fields. This latent wealth and energy helped determine the route of the Alaska Railroad. The railroad would use the higher grade coals of the Matanuska field to fuel its locomotives while hauling the lower grade coal to Anchorage and Seward for domestic use. After the last spike was driven in 1923 the Nenana field—next door to the new National Park—supplied Fairbanks, and also local consumers, including the park. Many small coal mines flourished briefly along the railroad, e.g., the mine at Railroad Mile 341, now within the enlarged park. Another small mine, in the original Mount McKinley National Park, near the East Fork of the Toklat River, was operated by the Alaska Road Commission to supply its camps during construction of the park road for the National Park Service. [6]

The mining story in the Denali region began coincidentally with the mountaineering saga. A kind of symbiosis evolved between the two very differently engaged groups of people: The miners provided hospitality and knowledge of the country; the visitors (not just mountaineers, but also USGS parties and ramblers of assorted kinds) brought news of the outside world and, because most of them were genteel sorts, provided polite new sounding boards for old arguments and opinions long since dismissed by the host miner's steady company. It was, after all, a fair deal.

A by-product of these exchanges were the writings of the visitors, which give us a contemporary view of the progress of the country and the people in it.

In the flurry of stampedes to the Denali region that began in 1903, prospectors came from north and south. Overflow from the earlier Fairbanks strike populated the Bonnifield and Kantishna districts. Prospectors from the entry port of Valdez crossed glaciers and mountains to open the Valdez Creek district east of Denali. And latecomers to the Cook Inlet strikes headed up the Susitna and Chulitna to the fields on Denali's south side. Trading stations and roadhouses sprang up overnight. Primitive packhorse and winter trails to the mining camps were blazed and brushed from the boat landings at heads of navigation. At these off-loading sites stores, saloons, and boarding houses appeared as if by magic. For Alaska's goldrush population included a large contingent of gypsy caterers to miners' needs and appetites. The toll gates at these places worked both ways: stampeders going to the fields spent their grubstakes for supplies and necessities; on the way back out, if their pokes held gold, they satisfied their appetites for booze, gambling, and women. Many hopefuls never made it to the gold fields. They lingered too long in the saloons, blew their grubstakes, and returned crestfallen to the towns. Serious prospectors and miners worked first, and, among those so inclined, binged second.

The Kantishna district exhibited all of these sequences and stages and shall be the main focus of the narrative that follows.

|

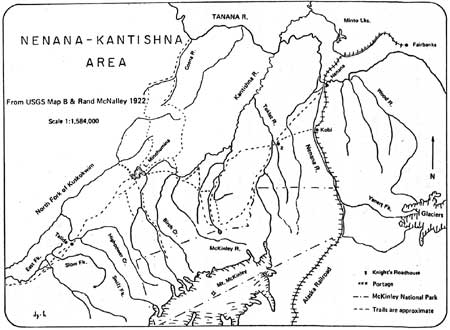

| Trails in the Nenana Kantishna Area, 1922. Dianne Gudgel-Holmes, Ethnohistory of Four Interior Waterbodies, 68. |

Though Judge Wickersham's claims on Chitsia Creek never paid a dime, his recording of them in 1903 attracted experienced prospectors to the Kantishna Hills. Joe Dalton found colors on the Toklat in 1904. Joe Quigley and Jack Horn staked Glacier Creek early the next summer. Their filing of claims on a quick trip to Fairbanks caused excitement and the rush began. Meanwhile, Joe Dalton and his partner had shifted southwest from Crooked Creek of the Toklat drainage to Friday and Eureka creeks which flowed into Moose Creek. Their staking of these rich diggings coincided with the arrival of the first stampeders in mid-July. Within weeks the 2,000 to 3,000 argonauts had staked every drainage in the Kantishna from mouth to head, and some prospectors were already probing the benches and ridges. A small fleet of steamers and launches carried people, gear, and supplies up the Kantishna and Bearpaw rivers as far as they could go. Instant boom towns sprang up: Diamond and Glacier City on Bearpaw River; Roosevelt and Square Deal on the Kantishna. The tent metropolis of Eureka, at the Eureka-Moose Creek junction, was the last stop before the miners clambered and hauled themselves and gear up the creeks and over tundra ridges to the scattered claims. [7]

|

| Glacier City, 1906. L.M. Prindle Collection, USGS |

|

| Roosevelt, on Kantishna River, ca. 1917. Stephen Foster Collection, UAF |

Within 6 months the rush was over. The real miners quickly scooped up the shallow, rich diggings, which were localized in a few streams. By February 1906, disappointment began driving the frustrated thousands out. Winter trails—around the north side of the Kantishna Hills via Glacier City and Diamond, or the pack trail up Myrtle Creek and across a low pass to Clearwater Fork of Toklat River—carried contrasting traffic: backtrail losers going out, and more supplies and equipment for the winners, going in. [8]

For all but a few the summer season of 1906 proved disappointing, and the gradual exodus became a rout. U.S. Geological Survey geologist L.M. Prindle visited the district late that summer. He saw many abandoned diggings. On September 1, after trekking down Glacier Creek where a few men were working, he noted in his trip diary, "town of Glacier, a long line of abandoned cabins & 2 stores." [9] Diamond inspired a similar entry. The town of Roosevelt, isolated by 18 miles of swampy tundra from the creeks, was practically deserted. The few hangers-on and the many empty cabins in these places ". . . testified with depressing emphasis to the decadence from the activities of the previous year." [10]

Thus ended the brief glory days and began the hard mining. About 50 people remained. Over the next 15 years or so the Kantishna district remained stable. Each year some 30 to 50 miners worked their claims. They all continued their placer work, at decreasing levels of pay, and some of them actively prospected and staked hard-rock claims on the ridges. When USGS geologist Stephen Capps visited the region in 1916 he found 35 persons, most of them holdovers from the first stampede. At that time all pay still came from placer mines, but preliminary development of the hard-rock claims was underway. Capps forecast that eventually the lodes—containing gold, silver, and the sulphides of lead, zinc, and antimony—would probably outstrip the placers in value. [11] He noted that several miners wintered in the cabins at Glacier City, down in the timbered flats. It was better than hauling wood to their high summer camps in the barren hills, [12] and wintering game and furbearers could be taken in the woods.

|

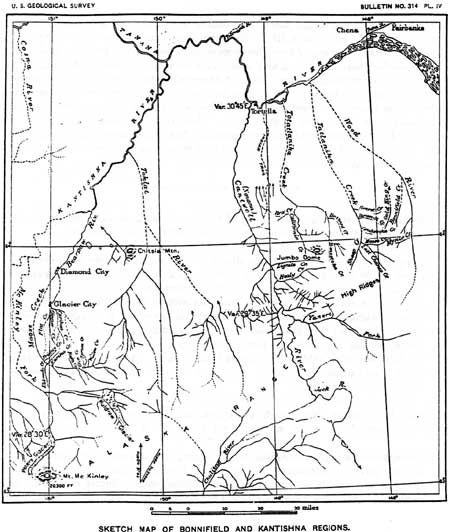

| Map of the Bonnifield and Kantishna Regions, 1906. Prindle, USGS Bulletin 314, Pt. IV. |

This was the distilled Kantishna community, this small group of durable people, whose hospitality became legend, whose daily anecdotes, as transmuted by literate visitors became the stuff of myths. They all hoped for better times. If they could get good transportation, thus reducing mining costs, many of the marginal creeks could be made to pay. If an all-weather wagon road came their way, maybe from the rumored railroad that some said would go through Broad Pass, then they could get in heavy equipment and go for the lode deposits. Always there were these hopes—and petitions and letters to the authorities that stated them and asked for transportation relief. Meanwhile, they exploited the shallow bench claims. From local materials they built automatic dams—boomer dams—which filled with water, then dumped themselves and filled again. The "splashes" from these dams washed away the heavy overburden so the miners could get to pay gravel under the deeper creek deposits. They hauled in some pipe and big nozzles and diverted water behind header dams so they could carve away the benches hydraulically. They subsisted on a combination of placer mining, hunting, trapping, and gardening. And they kept hoping.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

dena/hrs/hrs4.htm

Last Updated: 04-Jan-2004