|

CRATERS OF THE MOON

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 6:

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

OVERVIEW OF NPS TRENDS IN RESOURCE MANAGEMENT

Resource management in the National Park Service has followed several distinct trends. For the agency's first several decades, Directors Stephen T. Mather and Horace M. Albright promoted the park system for its scenic beauty. The thrusts of their policies were protection-oriented and reflected efforts to accommodate the public and develop a political constituency. During this period, manipulation of wildlife constituted the most common management policy. Although recommendations by Park Service wildlife biologist George M. Wright in the early 1930s began to alter the agency's practice of predator control, ecological management was still viewed as conflicting with development needs. The development of sound scientific resource management policies lay dormant following Wright's death in 1936 and the nation's entrance into World War II. During the postwar years, the boom in Park System visitation and the Mission 66 program, begun in the mid-1950s, brought the poor conditions of the parks into sharp focus. Predating the environmental polices of the National Environmental Policy Act, Mission 66 emphasized new facilities with little consideration for their effects on the environment. To some observers, the program appeared to benefit only the visitor through the expansion of roads and the construction of new facilities, and ignore resource management issues and scientific research. [1] To others, it reflected great strides in resource management, particularly where, for example, some visitor accommodations were phased out of environmentally sensitive areas, and the areas allowed to return to their natural states. [2]

In the 1960s, resource management policies began to exhibit a shift from the Mission 66 emphasis on visitor accommodations to environmental protection. Credited with having the greatest effect on park management was the 1963 publication by a team of scientists titled Wildlife Management in the National Parks. Commonly referred to as the Leopold Report, the study stressed that the agency should consider the composite whole of park ecosystems and their processes in management decisions, with a primary qualification being the preservation of original conditions. A highlight of the environmental movement was the 1964 passage of the Wilderness Act, bringing to a close ten years of lobbying by conservation groups, and initiating studies and designations for wilderness within the National Park System.

The environmental movement was further strengthened in the 1960s and 1970s by the support of the general public, which was becoming increasingly aware of and sensitive to environmental issues, including human impacts and the importance of ecosystems. As one historian of the movement has observed, the "major national parks came to be valued both as important parts of the global ecosystem and as unique, distinct areas where nature-altering human activities must not be allowed to take place." [3] In other words, environmental awareness was assuming a global perspective. Parks were not only scenic wonders but also environmental barometers, capable of interpreting the state of our environment through scientific research. The 1978 Redwood Act reaffirmed the NPS responsibility for preservation and committed it to this new understanding.

Trends in the 1980s continued to reflect this emphasis on natural processes, with a greater emphasis on a holistic management approach. Other emphases concentrated on ongoing resource threats, especially from external pressures, such as residential developments, and commercial and industrial ventures. The 1980 "State of the Parks" report recommended new policies for baseline resource inventories and monitoring in order to understand and mitigate resource deterioration. Today, Park Service resource management thrusts continue to focus on scientific research and emphasize the preservation of park processes, looking beyond the park's artificial political boundaries to the greater ecosystem that determines whether the park will be preserved. [4]

|

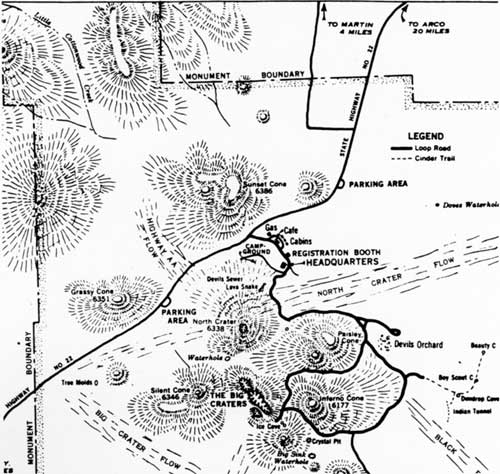

| The monument's principal features as presented in a tourist map from the late 1930s, one of the few maps identifying the "Devils Sewer" and "lava snake" just south of the campground. |

RESOURCE MANAGEMENT AT CRATERS OF THE MOON

At Craters of the Moon, resource management serves as a catchall phrase for management in general, for the protection of resources entails identifying threats and solutions. Generally speaking, resource management at the monument mirrors the phases of resource management that the park system experienced overall. Early resource management was that in name only, becoming more refined as the monument's administration evolved. Like most park units, the monument was virtually shut down during World War II, with resource management abiding by a "hold-the-fort" philosophy. The "formal" or organized era of resource management at Craters of the Moon commenced at mid-century with the Mission 66 program. Armed with a new physical plant and sufficient staffing in a time of escalating visitation and resource impacts, monument superintendents began producing resource management plans for the first time. In doing so, they developed the monument's resource management program.

MANAGEMENT PHILOSOPHY

Central to any program was a resource management philosophy; the monument's stems from its enabling legislation, the National Park Service's 1916 Organic Act, as well as other relevant federal laws and NPS policies and regulations. As outlined in President Calvin Coolidge's 1924 proclamation establishing the area, monument administrators have endeavored to manage the area's resources for their unusual scientific and educational values and general interest. The one statement that articulates best the monument's current management philosophy dates to the 1966 resource management plan, but is restated in similar form in the most recent plan:

It is important to recognize the deceptively fragile characteristics of the volcanic structures and their associated natural features found within the monument. Careful management of human use of the area is necessary to prevent permanent and irreversible damage to the resources and to ensure that the natural state of the monument will be perpetuated for future generations. [5]

The area's management philosophy was also influenced by its classification as a natural monument from 1964 to 1977. In this respect, Craters of the Moon has been managed to protect its primary feature, the basaltic volcanism of the Great Rift. Other natural resources recognized by management are the biological phenomena of the contorted landscape. By comparison, cultural resources play a minor role in the monument's resource management program. Yet the experiences of early and contemporary humans within and near the monument expands our understanding of the volcanic zone. Indians, explorers, and pioneers in the region during the 19th and early 20th centuries offer administrators physical, written and visual documentation of the area's resources. Interpretive programs present both natural and cultural aspects of the monument, and help protect the monument by educating the public in the two disciplines. A comprehensive research program concentrating upon the scientific and cultural resources of the monument has linked these diverse areas of resource management. Whether in natural or cultural history, these types of investigations allow managers to gain a broader context for the monument's resources, and achieve an understanding of changes to the area over time. Providing visitors with appropriate recreational experiences, while not adversely impacting the monument's resources, forms another management objective. Attention to all of these matters goes toward fulfilling the area's mission.

Overall, management of the monument's resources addresses issues relevant to early administrations, specifically in the categories of geology, wildlife, and vegetation. Collection, vandalism, and other forms of human erosion persistently impact the area's volcanic features. Similarly, illegal hunting of mule deer has been the most common threat to the monument's wildlife, as has been trespass grazing to the area's vegetation. This trend reflects a strong historical continuity in management. It also reflects the fact that past management was aware of only the most obvious threats. Advances in resource management demonstrate a growing awareness of more subtle threats, which, like changes in air quality, are difficult to detect, yet the impact of which could be profound.

MANAGEMENT ZONES

Resource management at Craters of the Moon falls into two general management zones, natural and developed. Most telling of the monument's zoning is that of the area's entire 53,545 acres 43,243 are designated wilderness. That leaves 10,302 acres to comprise the core of the monument's administration and use; the landscape includes the most dramatic features along the Great Rift, encompasses the foothills and flanks of the Pioneer Mountains to the northwest as well as park development, visitor services and facilities, and the major interpretive motor route through the monument. [6]

Since most of the monument lies within a designated wilderness, the majority of visitor activity and resource damage takes place in the frontcountry. The harsh and remote environment of the wilderness area attracts few visitors. The northern unit, considered a backcountry, but open to day hiking and biking, sees a small amount of activity--its use regulated to protect the monument's water supply and deer herd during hunting season. Moreover, the frontcountry is the region where the monument's outstanding natural features are located, easily reached by the scenic loop drive and its adjoining pullouts and trails, thus concentrating resource impairments. However, this neither minimizes the potential for nor exempts other sites from internal or external threats.

PROGRAM DEVELOPMENT

The formation of a resource management program can be seen, for the most part, in resource management planning and through the monument's various phases of administration, providing further context for specific issues discussed later.

THE EARLY YEARS AND THE SELF-MANAGING MONUMENT

Formal planning for a resource management program did not occur until Mission 66, yet the theme that the monument was self-sustaining pervades the development of the monument's resource management program. Horace Albright established this precedent in the fall of 1924. After visiting the lava region, he asserted that it was worthy of Park Service protection; however, he assumed that the reserve's remoteness and impenetrable landscape secured its resources from threats such as vandalism. Albright worried more about the quality of employee guarding the monument than he did about visitors stealing rocks. [7] Thus most management activity during this period centered primarily on the development of the physical plant. And while some improvements would help manage the resources, they were done with an eye toward visitor use.

The emergency work programs during the 1930s reflected resource management issues, even though they, too, were weighted on the side of developing tourist accommodations. Custodian Albert T. Bicknell, for instance, determined that the construction of better roads, trails, and visitor facilities would contribute to the alleviation or diminishment of resource management threats.

Because of the war, by the late 1940s planning efforts that addressed resource management in any form were static. Better public access and low visitation collectively caused little in the way of irreversible damage to resources, it was believed. Like Albright some twenty years before him, Region Four Director O. A. Tomlinson summed up the situation in 1943 by remarking that the very nature of the monument's primary resource protected it from significant impacts. The formidable barrier of lava prevented serious external threats from fire and humans. Since visitors circulated through the monument by way of the unpaved road system, little stress was inflicted on the resources. From Tomlinson's perspective, these factors, as with the monument's administration in general, caused the area's resource management program to continue its nearly self-operating manner. [8]

MISSION 66

With the 1950s came not only new physical development but also a definitive resource management program at Craters of the Moon. Contributing to this trend were improved national highway access to the monument, a postwar surge in tourism, and establishment of the Atomic Energy Commission's facility east of Arco. The subsequent exponential rise in visitation exposed the area's resources to increased impacts. Along with an emerging environmental ethic in American society and the Park Service's efforts to accommodate rising visitation, these catalysts led to concerted resource management planning efforts at the monument.

Mission 66 provided the necessary facilities and staffing for a resource management program. As part of the program, the monument outlined its resource management philosophy. Superintendent Everett Bright in his 1956 prospectus, for example, stated that management should protect the primary volcanic resource, and should also recognize the biological elements contained in the lava landscape as worthy of preservation and management because animals and plants were valuable for their adaptation to the harsh environment. Although a day-use principle would be employed to manage the resources, the installation of an interpretive program was essential so that formal education of the public could commence and be effective in the battle for resource protection.

Building upon the prospectus, the Mission 66 master plan, drafted in 1960 by Superintendent Floyd Henderson, followed up on the biological emphasis, calling out the importance of adding the Carey Kipuka because the site complemented the monument's scientific and educational mission. The plan also expanded the scope of resource management to include cultural resources, both prehistory and history, for what human activity revealed of the lava region. But natural resources received primary attention over the next several decades.

The watershed year in resource management proved to be 1966. As part of the Park Service's systemwide initiative, the monument prepared its first resource management plan, which was also the first of its kind in the Park Service's Western Region. Written by Superintendent Roger Contor and staff, the Resource Management Plan for Craters of the Moon National Monument formalized resource management at the monument. It addressed the resource itself instead of development, and thus represented a new direction in management. For the first time, one document defined the monument's resource management philosophy and guidelines, inventoried existing resources, attempted to gauge their original conditions, and analyzed appropriate management of those resources. [9]

In general, the principal objective of the monument was to preserve the remarkable and weird volcanic phenomena of scientific value and general interest, as first witnessed by European explorers and pioneers in the early 19th century, in addition to conserving the formations for the enjoyment of future visitors. As a result, Contor's plan mandated the control of human use and development so as not to degrade the original conditions, or, in other words, the "vignette of primitive America." All people, the document asserted, should have the opportunity to witness this landscape of suspended violence, for all its starkness and surprising forms of life.

Conceptually, these resource management principles expressed the main tenets of the 1963 Leopold Report. In this sense, management framed policies necessary to preserve and possibly restore the ecological scene as first viewed by Europeans. In keeping with the monument's designation as a natural area, the document concerned itself primarily with natural resources, and secondarily with cultural resources for what the latter illuminated about the "original" landscape of the previous century. The plan recorded four basic areas of resource management: geologic, wildlife (plant and animal), resource use (recreation and development), and research.

Overall, these resources were analyzed for change over time through historical and scientific methods. And it was determined that, save the extirpation of grizzly bears, wolves and bison, and the presence of the water system in the Little Cottonwood Creek drainage, no significant disturbance of original conditions existed, and thus there was no foreseeable reason why the scene from the early 1800s could not be perpetuated. Therefore, protection of existing rock, wildlife, plant, water, and human-related resources rather than environmental manipulation constituted resource management's major focus. Guidelines stressed that fragile geologic features were to be considered a "non renewable" resource and managed as such. Biological resources were to be considered "renewable," highlighting the fact that fire and wildlife restoration, for instance, could occur if they fit the original scene. Finally, comprehensive research was to form the backbone of the embryonic program.

POST-MISSION 66

In the 1980s two resource management plans (1982, 1987) succeeded the original plan. The reason for the hiatus between 1966 and 1982 stems from both monument and NPS activities during the period. Immediately following the publication of the 1966 plan, Superintendent Paul Fritz replaced Roger Contor. Fritz, busy with duties as--superintendent, state coordinator, and keyman for Idaho's Sawtooth Mountains study--lacked the time and energy, as well as staff to update the resource management plans. Replacing Fritz in 1974, Superintendent Robert Hentges determined that the monument was in need of a new direction in its resource management practices, yet his 1976 statement for management reveals little though in the way of any new issues, trends, or changes in resource management, except for its mention of external threats, such as the potential mining operations near the monument.

In fairness to both Fritz and Hentges, the 1966 plan served its purpose well, even though its emphasis on original conditions became outmoded as resource management moved toward "true ecology." Moreover, not until the early 1980s did NPS policy begin stressing the importance of updated resource management plans, the preservation of park processes, and comprehensive research. Research enabled managers to better understand the park ecosystem and address possible solutions to issues of resource deterioration while still allowing for visitor use. By far the most significant resource management thrust at Craters of the Moon has been placing resource knowledge as the cornerstone of resource management.

The project employed to meet basic research needs was the Baseline Resources Inventory (BRI), initiated in 1983. The goal of the BRI was to identify and document the monument's resources, both natural and cultural, and their existing conditions. The baseline study attempted to account for all the components comprising the monument's ecosystem in order to fulfill three objectives: to provide a standard of resource conditions; to enable managers to detect change to these resources through monitoring; and to provide information to both qualify and support management actions and plans.

In the late 1980s, Gerry Wright, of the University of Idaho's cooperative park studies unit, developed a comprehensive assessment of the monument's baseline information. The 1988 Review of of Scientific Literature at Craters of the Moon National Monument was a significant first not only for Craters but also for the Park Service. This was the first time a comprehensive look had been made at our state of scientific knowledge of a park area and an attempt to determine where the voids in knowledge existed. Craters of the Moon served as a pilot area for this project as well as the Natural Resources Data System. This marked a shift in the NPS approach to resource management in the form of baseline data collection and data management rather than the more typical crisis management. During this period the monument developed a Geographic Information System at the CPSU at the University of Idaho; it also developed baseline transects during this period as well, including those for vegetation and breeding birds; it also developed exclosures in its northern end on Bureau of Land Management land to monitor vegetation changes as the result of fire.

Although the BRI sought to be comprehensive, its benefits were not instantaneous, nor could it eliminate traditional problems. In the case of geologic features impacts grew, with management continuing to seek an uneasy balance between preservation and use. Other geologic management issues arose with the need for cave management planning and seismic monitoring. Developing a comprehensive fire management plan demanded attention, too, especially in the wake of the Yellowstone fires of the 1988. External threats mounted and were recognized as one of the most pressing issues. Pollution of the monument's Class I airshed, for instance, could lead to deterioration of an array of resources, leading to both vegetation studies and visibility monitoring.

FUTURE TRENDS

As documented in the 1992 resource management plan, by the early 1990s the monument possessed an adequate baseline inventory of its major resources, and building a monitoring program to measure resource change posed the greatest challenge for the future. [10] Furthermore, other work still needs to be done to complete the data base in the areas of cave management, air and water resources, specific plant species studies; deer winter range use and distribution, invertebrates, amphibians, and reptiles. With changing Park Service attitudes about cultural resources in natural areas and the growing compliance with federal preservation laws and NPS regulations, cultural resource management has received greater attention, yet still requires more research.

Untold numbers of external threats present another area of high concern. Potential pressures outside the monument that need to be addressed are renewed interests in mining and mineral exploration adjacent to the monument, the development of commercial recreational facilities near the boundaries, the encroachment of exotic vegetation within the northern unit, and noise intrusion from airplane overflight activity. Still dominating all external threats, however, is the degradation to the monument's Class I airshed from both particulate and gaseous pollutants. While visibility monitoring has been conducted since the late 1980s, gaseous pollutant monitoring is still needed, as is an air quality management plan.

To address resource management issues brought on by rising visitation, interpretive programs are incorporating resource management topics. On the other hand, the new general management plan suggests relieving present and future congestion through developments--new visitor facilities and reconstructed roads and trails. In addition, should the proposed expansion of the monument occur, new issues and concerns for resource management would come to the forefront.

Ultimately, resolving old problems retains a prominent place in the future of resource management. This is significant from a historical perspective because the same issues affecting past managers will, in all likelihood, influence future managers. Among these are: revising the northern boundary to end trespass grazing and illegal hunting, completing the long-awaited cultural resource inventory, maintaining an adequate water supply with increased use, and, as always, dealing with the inherent impacts to volcanic features.

One bright spot in the future of resource management promises to be the newly created resource management division in 1992. Formerly resource management was included with visitor protection, but the emphasis on personnel trained in resource management has grown. The first permanent resource management specialist position was created in 1989; it was followed by the new division, which consists of a chief, a permanent position, and a biological technician, a permanent, subject to funding position.

NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT: ISSUES AND HIGHLIGHTS

Natural resource management at Craters of the Moon National Monument constitutes the majority of management concerns. Historically, protection of the geologic resources has been the primary management focus because the volcanic formations were the basis for the area's creation and are its central theme. Protection of wildlife, vegetation, water, and air quality have formed a secondary but nonetheless important management emphasis. In all cases, custodians and superintendents have pursued policies of mitigation, education, and enforcement to strike the balance between preservation and use of the monument's varied natural resources.

GEOLOGIC RESOURCES

Attracting the majority of visitor activity and visitor related impacts, the lava formations are plagued with the chronic problems of illegal collection, vandalism, and other forms of human erosion. Unlike biological resources, the volcanic features are frozen in time. Where grass or trees can regenerate, only a new eruption can replenish the lavas. Until then, they will breakdown. While a natural process, erosion is accelerated by visitor contact. Federal laws and National Park Service regulations prohibit unauthorized collection and vandalism, yet both exist. [11]

To the untrained eye, the lavas seem indestructible, when in fact the opposite is true; they are deceptively fragile--realized all too starkly by the disappearance of known formations and the degradation of others. Thus efforts to protect the sensitive terrain have required vigilance from monument managers. Balancing preservation and use has led to changes ranging from modifications in the types of acceptable visitor behavior and activity to rehabilitation of popular features. Similar to other aspects of Craters of the Moon's management, the long term effects of depletion and damage from visitor use were not readily apparent nor rigorously managed until mid-century when visitation accelerated and the monument's administration grew in response to increasing pressures. Although the majority of damage occurs within the monument's developed interior, among the outstanding natural features, resource problems are not isolated to these sites alone. Finding a way to protect the geologic resources has meant combating the perception that the already broken, twisted, and contorted landscape is not susceptible to alteration, when it is even by the most incidental human contact.

Impacts to the lava terrain, many of them through benign actions, predated the establishment of the monument. At the turn of the century, scientific groups entered the lava flows of Craters of the Moon and by the early 1920s unrestrained sightseers roamed the formations by foot, horse, or auto. As promotion of the area accelerated, so did visitation and souvenir hunting. Lava bombs, tree molds, squeeze tubes, and loose fragments of aa and pahoehoe lava were among the volcanic specimens attractive to scientists for research and to individuals for souvenirs. Commercial interests, to a degree, also threatened the reserve's "great scientific and scenic wonders." Before the monument was established, at least one entrepreneur had "had sold several hundred dollars' worth of curiously formed lava bombs" taken from "the slopes of the volcanoes." [12]

Even after the Park Service placed Custodian Samuel Paisley in charge in 1925, it was evident that fascination with volcanic rocks would persist. In January, the Arco Advertiser reported what was then and is now a common reason for impacts to geologic features: "There is the general desire on the part of visitors to take home specimens of the different kinds of lava to show friends." Similarly, universities were conducting scientific outings at an increasing rate. [13] Perhaps the most famous rock collector was Park Service Director Horace Albright himself. Demonstrating the attractive qualities of the monument's lava rocks, Albright "tried to carry an armful of `lava bombs' for half a mile or so" during his 1924 inspection, "in order to make them available for photographing." Sensing his mistake, however, he concluded: "I finally got them to the car, but resolved that I would never again gather specimens at Craters of the Moon National Monument." [14]

|

| The crowded conditions of Opening Day, 1939, give some indication of growing pressures on monument resources. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

Taking Action

Protective measures at this early stage were employed out of necessity and were mostly informal. Impacts like collection do not appear as issues in early Park Service reports. With low-level tourist use, custodians were better able to monitor visitor activity, or at least contact visitors as they entered the area. Moreover, Custodian Paisley's creation of an outdoor display of lava samples in 1926 may have alleviated some rock removal, allowing visitors to touch but not take volcanic specimens. [15] Even so, impacts to geologic resources present at the monument's inception evolved into an ongoing issue that area managers eventually needed to address.

The Posse Dash

A variety of visitor activities jeopardized volcanic features. During the monument's formative years, for instance, damage to geologic formations occurred through a seemingly innocent activity--the annual Opening Day celebration conducted at the monument every spring since the area's creation. The fanfare included picnics, speeches, music, and the famed Sheriff's Posse Dash, all of which was sponsored by the Butte County Chamber of Commerce. The event attracted several thousand spectators. Overflow parking covered both sides of the entrance road and filled the campground. Over all, the festivities formed an important public relations activity and constituted considerable work for the small monument staff preparing for and controlling the crowds.

As a public relations activity the event was a success, but in terms of resource management, the celebration proved destructive. Beginning in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Superintendent Aubrey Houston reported that Opening Day vandalism and collection were on the increase. Houston's experience in May 1952 is as amusing as it is enlightening:

Sometime during the late evening rush of visitors leaving the monument on Opening Day, the 25th, one of our less law-abiding [sic] citizens made off with our prize specimen of breadcrust bomb, which makes me [sic] very unhappy and jars my faith in human nature to its very foundation. I even dreamed that I awoke one morning and found that the whole collection had been carted away. [16]

By 1963 change was in order, and Superintendent Daniel Davis toned down the celebration. It was not only labor intensive for his staff but also damaging to monument's resources. The Sheriff's Posse Dash, an opening ceremony where flag-bearing riders raced horses through the monument's sensitive cinders, "tore the place up," Davis recalled. Vegetation as well as cinders and hardened lava suffered. For these reasons, he eliminated the posse dash altogether. Davis realized that this was a delicate issue. The local groups used the area as a personal playground (as they had for years), and he was an outsider expounding new ecological perspectives on resource management. His decision did not win him new friends within the Arco community and alienated him from some of its members. Given the decades of serious impacts to the geologic resource, Davis felt justified in his decision. Even though he formally eliminated the Posse Dash, Arco community members have broached the subject with more recent superintendents. Robert Hentges, approached regarding the horseback event in the mid-1970s, decided against reinstating the festivity, for the same reasons as Davis. At present, the Sheriff's Posse Dash remains a part of the monument's colorful past. [17]

|

| Lining up for the Posse Dash, a popular yet destructive event at Opening Day, 1961. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

Buried Treasure

Another colorful element stems from a rather humorous anecdote with potentially serious consequences. Local legend, as recorded in the 1937 Idaho: A Guide in Word and Picture, has it that outlaws headquartered in the cinder and spatter cones of Craters of the Moon, and there hid their gold. [18] It was only a matter of time before a request came in to excavate the monument's "hidden treasure."

In November 1949, several individuals from Boise, Idaho, aware of the legend, asked permission to dig for the secret cache supposedly in or near the formation known as the "Old Man of the Craters" on the southern slope of Paisley Cone. Believing they had located the site through suspect means, Superintendent Aubrey Houston denied their request until he gained confirmation from his superiors. For the Park Service, the situation caused a policy dilemma. At first, the Service "reluctantly recommended" that an excavation permit might granted, because this was consistent with agency policy and there appeared to be no valid reasons to deny the request. However, the proposed excavation was to occur in an area of monument's highest "value and use" and would leave an irreparable landscape scar. Stating that the excavation was inconsistent with the monument's purpose and the Park Service's mission, Western Region Director Lawrence C. Merriam denied the treasure hunting permit in April 1951. Nevertheless, the story resurfaces periodically, exciting more interest and eliciting more agency denials. [19]

"Hot Rods" and Cinder Cones: Off-Road Driving

A more destructive form of human erosion originated in the monument's early years as well. Driving across the cinders and fragile geologic features at the monument occurred prior to and after the monument's establishment. Both explorers and sightseers left the primitive road system and ventured unrestrained (as did pedestrians) across the delicate cinders creating troughs and tracking footprints in the process. Compaction of the sand-like cinders left an indelible image for years, altering the color of the surface in places and leading to the growth of vegetation in the depressions. In addition to these "cosmetic" scars, early auto travelers frequently sunk into the cinders, spinning deep ruts and breaking limbs off of limber pines for traction. [20] Brittle, hard-surfaced lava formations also suffered permanent damage. This situation was perhaps inherent to Craters of the Moon because of its enticing rolling terrain and informal road system. At first developments played an important role in mitigating this destructive activity. Custodian Albert T. Bicknell--with the help of the emergency conservation work programs in the early 1930s--tried to resolve the issue through the erection of rock barriers along the monument roads and the establishment of more formal trails to prevent cars and their drivers from wandering off onto cinder slopes.

However promising these developments appeared, they were not enough of a deterrent some thirty years later. Even after Mission 66 modernized the monument's loop drive and adjacent roads, rising visitation increased number of incidents, suggesting that the problem was here to stay. Confronted with a rash of off road-driving by local youths from Arco in March 1961, Superintendent Henderson increased protection by initiating night patrols. He exhorted that such actions were contemptible, should be actively opposed, and viewed as "an act of vandalism." [21]

Two years later, Superintendent Daniel Davis acted on this directive and recorded what is probably the first enforcement against off-road driving at the monument, writing that the Butte County Sheriff returned four California youths to Craters of the Moon for driving across cinder cone slopes with their "hot rods." Davis punished the youths by making them rake out their tracks, a policy incorporated into the first resource management plan. [22] Active enforcement and public contact, as practiced by Davis, helped to alleviate but not cure the problem. In a small measure, the problem persists; the wide trail up Inferno Cone, for instance, occasionally attracts four wheel drive vehicles. [23]

Cinder Hauling and Vandalism

Off-road driving was indicative of rising damage overall to geologic features in the 1950s with expanded protection forming the management response. For example, in October of 1952, Superintendent Houston discovered that cinder hauling was taking place since the cinders were attractive for landscaping, an occurrence likely attributable to the region's construction boom. After discovering the activity, Houston increased patrols, two to three times a day, and resolved the problem. [24]

Outright vandalism during this period, however, underscored the obstacles a small staff encountered protecting the resources. In August 1953, Ranger Robert Zink discovered that some hikers had ventured four miles south of the Tree Molds parking area to Trench Mortar Flat where they "attempted to dig up one of the lava trees," vertical tree molds believed to be the only type in existence. Zink lamented that a lack of personnel to patrol the closed area (now wilderness) or funds for protective fencing found the administration unable "to control the activities of such visitors." [25]

Reflecting the expanded administrative capacity set in motion by Mission 66, Superintendent Henderson took steps to offset vandalism in other areas of the monument, initiating the construction and installation of the gate at Arco Tunnel in May 1961. The gate also provided for visitor safety. And in August, the superintendent increased ranger patrols "in an effort to discourage the removal of rock samples and vandalism to some of the more heavily visited features." [26] As part of this protection and public information program, two months later Henderson erected five signs warning "visitors that specimen collection is prohibited." [27]

Devil's Sewer: The Lost Feature

Increased patrols, warnings, and signs, however, failed to completely prevent the destruction of volcanic features. The impacts represented a process that transpired over a long period of time, and by 1962 their effects appeared in the Devil's Sewer formation situated in the North Crater Flow. [28] The lava section contained a variety of interesting features including aa and pahoehoe lava flows, a pressure ridge, squeeze-outs, monoliths, common plant life of the pahoehoe habitat, and the famous 1,350-year-old Triple Twist Tree. The central element of the area was a long lava tube known commonly as the "Lava Snake." Accessible from the first turnout along the loop drive and by a 300-yard trail, the site received a great deal of use. In the late 1940s and early 1950s Superintendent Aubrey Houston called attention to its impairment intensified by the Opening Day celebration, whereby "Vandalism is a constant threat to some of the most interesting features. As an example, the Lava Snake has been so badly damaged by souvenir hunters or destructive vandals as to be unrecognizable." [29]

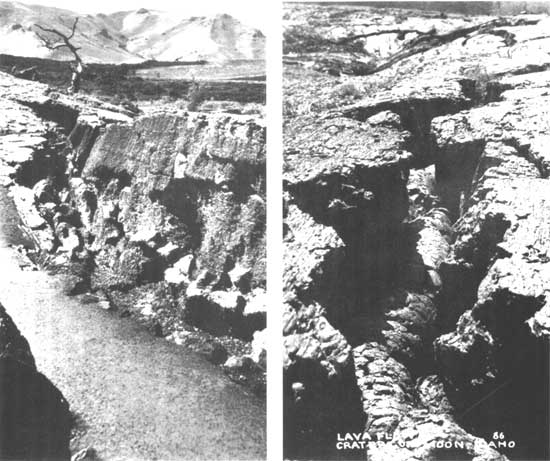

Almost forty years of this activity and off-trail hiking across the brittle rock eroded the feature until it had virtually disappeared. In September 1962, Superintendent Merle Stitt pronounced its destruction: "once a 35-foot squeezed-out tube of geological importance, [it] has been completely destroyed by thoughtless visitors. Approximately 2-1/2 feet of this formation remained at the beginning of the 1962 travel season." [30] Afterwards the area was still interpreted but the feature's diminishment redirected interpretive efforts to other features within the North Crater Lava Flow. [31]

|

| The photo at right reveals an intact portion of the "lava snake", ca. 1940s or 1950s; the photo at left feature's destruction, ca. 1962. Note the proximity of the trail to the feature. (Left photo, CRMO Museum Collection; right photo, courtesy Glenn Hinsdale) |

SETTING DOWN GUIDELINES: THE 1966 RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN

Impacts to the geologic resources eventually found their way into monument resource management policy. The destruction of the Devil's Sewer lava tube exemplified the deceptive fragility of lava formations and the long-term effects of unauthorized collection and uncontrolled human use. Other features were equally susceptible to loss. The 1966 resource management plan documented the gravity of the situation and set down guidelines to mitigate destruction of the monument's "non-renewable" volcanic resources.

Speaking of collection, Superintendent Roger Contor stated in the report that "Craters of the Moon has passed the point of diminishing returns regarding collection of geologic specimens." From now on, monument policy would consider the collection of cinders and lava samples within the monument no longer necessary or appropriate because plenty of similar examples could be found outside the area's boundaries. Volcanic phenomena such as tree molds and lava bombs were believed to be unique to the monument; considering their past collection and depletion, "those remaining are now invaluable." [32]

Therefore, given the sparsity of volcanic phenomena in the monument's core, Contor noted that only bone fide scientific collection should be allowed throughout the monument as a general rule, and that the administration should carefully screen each request. A college or university's interest in building a "representative collection" of the monument's geology "is no longer adequate justification." Groups of geologists and students from across the country visited the monument annually in search of lava bombs, for example, an activity referred to in "local universities as a 'bomb raid on the Craters.'" [33] This was no longer an acceptable activity.

Mitigation of collection would best occur through the adherence of strict guidelines for specimen removal for scientific research, the expansion of a public awareness campaign to reduce specimen collection and collateral vandalism, the continuance of roving patrols with additional rangers making visitor contacts, as well as the establishment of state laws that would prosecute rock collectors and vandals in Idaho judicial courts. [34] In the case of the latter, Contor announced that in March 1966:

The Butte County Commissioners passed an ordinance...(No. 198) prohibiting any act that "disfigures, defaces, destroys or removes any object or thing of archaeological, historical or geological interest or value on private land or within any public park in Butte County." This ordinance will enable Monument personnel to utilize the Butte County Justice of the Peace for the above violations. [35]

Damage to the monument's volcanic features caused by regular visitor activity received equal attention in the plan. The Devil's Sewer was but one example of unrestrained visitor exploration. Deterioration was often subtle, detected not necessarily from the ground but rather from the air. As Superintendent Contor observed, from "an airplane one can easily spot areas of human use by the red-brown coloring of the broken surface, as contrasted with the oxidized grey of the undisturbed surroundings. Even casual walks into the roadless areas create minor but cumulative damage." [36]

Contor believed that vandalism or social trails created by visitors bored with a certain trail or site could be avoided by the construction of loop trail systems. He thought of Devil's Orchard Trail as a good example, and mandated in the plan that where possible present and future trails should follow this precedent--specifically, North Crater Flow interpretive trail, Indian Tunnel trail, and if feasible, the route between Beauty and Surprise Caves. [37]

Visitor protection also played a role in resource protection. Echoing earlier concerns over destruction to fragile features and increased use, Contor recommended that the installation of "protective walks, ladders, enclosures or barriers in the tree mold and Spatter Cone area" along with other sites should be built commensurate with "public use demands." As for visitation, control of people was key to the success of the resource management program. [38]

Rising visitation exposed design flaws and resource threats. The campground, for instance, was too small for current use and thus projected increases in visitation, and more importantly, it was located in a sensitive area, the North Crater Flow. Therefore, Contor proposed closing the campground and possibly relocating it in the Little Cottonwood Creek basin to further protect geologic formations. [39] Similarly, anticipated growth in visitation required an expanded circulation network to avoid congestion and resource impairment. Contor thus offered the expansion of the loop drive around Big Cinder Butte as a possible solution. [40]

Although neither proposal was implemented, [41] protection of the volcanic resources showed significant improvements with the drafting of the 1966 plan. It established policy guidelines adhered to over the next several decades that to this day remain largely unchanged. Managers, however, would always be faced with a "winless" situation. As Superintendent Robert Hentges noted in 1980, for instance, the "removal of volcanic phenomena still plagues the park and probably always will, regardless of the information we attempt to provide the park visitor concerning this problem." [42] Today, collection continues to be a problem along with other forms of human erosion. All are managed through aggressive interpretation and enforcement, including "on-site interpretive programs, articles and regulations in handout material, signing, personal contacts and law enforcement actions." These methods, while not stopping injury to lava features, have struck, in most cases, a workable balance. [43]

SITE-SPECIFIC DISCUSSION: FRONTCOUNTRY GEOLOGICAL FEATURES

While general policies to protect the lava terrain were in place by the mid-1960s, the most dynamic resource management efforts have taken place within the past twenty years, focusing primarily on the frontcountry sites. These areas--the North Crater Flow, the Devil's Orchard, Inferno Cone, Big Craters and Spatter Cones, Tree Molds, and the Caves Area--are located along the loop drive. Together, they characterize the monument's intrinsic value, uniqueness, and inherently "weird and scenic" qualities mentioned in the enabling legislation. In a larger sense, this collection of outstanding features exemplifies all the major features found within the reserve, as well as the problems associated with their management. Because the various sites are close together, connected by the seven-mile road system, visitors can experience the essence of Craters of the Moon up close and in a short period of time (2-3 hours). Yet this attribute also contributes to site deterioration since the frontcountry receives the most concentrated visitation, an average of 200,000 annual visitors, the majority of whom visit during the summer months. [44] Consequently, monument administrators, faced with increased impacts, have implemented programs to better protect and rehabilitate the frontcountry lava features while still allowing for visitor use, making the region a continuing resource management concern.

North Crater Flow

The North Crater Flow presents fine examples of ropey pahoehoe and aa lava flows, along with the remnants of crater walls transported by the same flows. The closest site to visitor facilities, the area received heavy use as the disappearance of the Devil's Sewer lava tube in the early 1960s attests. Although the short nature trail at the North Crater Flow introduces visitors to the monument, the interpreted area lies adjacent to the campground located in the same flow, but separated by a low ridge. Over time, social trails have radiated from the campground as visitors explore the lavas or short-cut over the hill to reach the site rather than walking the loop drive. Considering the North Crater Flow as sensitive terrain, Superintendent Contor suggested removing overnight camping facilities from the area altogether in the mid-1960s. Subsequent management plans failed to see the necessity, deeming the relocation of the campground to the northern unit as administratively unfeasible. Furthermore, by 1980 the value of the north end as a high desert ecosystem was recognized precluding any development.

By 1991, the geologic resources of the ridge separating the campground and North Crater Flow parking area had sustained serious impairment, and managers were compelled to seek corrective action. Unable to move the campground, they instead concentrated on the poor circulation design. Campers were more inclined to traverse the ridge since the alternative was the loop drive, which makes for neither safe nor pleasant walk. For these reasons, Superintendent Robert Scott undertook a trail construction and rehabilitation project in the summer of 1991, establishing "a designated trail from the campground to the North Crater Flow area." By obliterating informal trails, developing a regular trail maintenance and rehabilitation schedule for social trails, and continuing enforcement of regulations to prohibit off trail use in the North Crater Flow, he believed, will result in "long-term rehabilitation/protection of a sensitive and heavily used area." [45]

Devil's Orchard

Here rafts of lava fragments stand like islands in a sea of cinders, possibly marking the vent of an ancient cinder cone. Lava bombs lie scattered about the cinder slopes, and springtime flora displays are glorious in the cinder gardens when dwarf monkey-flowers mat the ground with a magenta cast. One of the oldest sites visited in the monument, Devil's Orchard attracts a large number of visitors who tour the "weird" features along the short interpretive trail.

Built in 1963, the third of a mile, self-guided interpretive loop trail was part of the monument's developing interpretive program, the first area to concentrate on the lava landscape's natural history. Although superintendents such as Roger Contor favored the loop trail design for its protective qualities (circulating visitors in order to hold their interest and keep them on the trail), the design was not effective enough. Social trails braid the area; vandalism is frequent, and rock collectors have scoured the vicinity of its lava bombs. Because of its role in interpretation, Superintendent Scott approved a pilot program in the summer of 1991 to interpret both the site's and the monument's natural resource management problems at Devil's Orchard, thus involving visitors and making them more aware of resource impacts. The experiment was considered successful and on the "cutting edge" of interpreting natural resource management; a formal trail rehabilitation program and revised interpretive approach were underway in 1992. [46]

Big Craters-Spatter Cones

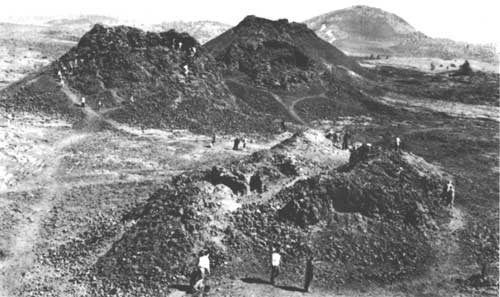

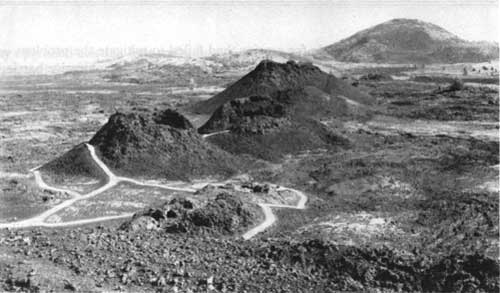

One of the most distinctive and popular sites at Craters of the Moon is the Crystal Fissure Spatter Cones. They formed along the Great Rift when clots of pasty lava stuck together during an eruption, building steep-sided, chimney-like vents in the process that look like miniature volcanoes. The spatter-cone chain at Craters of the Moon is considered one of the most perfect chains of its kind in the world. The chain is composed of three main vents and a fourth and smaller vent in the foreground, called Snow Cone. [47]

Because of their popularity, the Spatter Cones have been the focal point of the most intensive management and rehabilitation ever undertaken at the monument, most of it within the last decade. The vents, in a sense, epitomize the management of volcanic formations at the monument; they are both beautiful and fragile and open to public viewing and contact. Over the years, unchecked exploration wore a lacework of trails into the sides of the cones, sloughing off the delicate cinders on their slopes, caving in sections of one crater's wall, and eroding more than two feet of material from the rim in the process. Visitors throwing rocks and garbage into the vents altered the insulating properties of the features, raising the bases, and causing the possible disappearance of perennial ice. At risk as well was visitor safety, not only from climbing the cones but also from falling inside. Unrestrained activity altered the appearance and integrity of the spatter cones by the 1960s, making imperative rehabilitation efforts for their preservation and use.

Site History and Management

Human erosion of the spatter cones was evident early in the monument's history. Photographs from the early 1920s compared with those of late 1930s, for example, display the conical vents with social trails worn into their sides. [48] At the same time, resource management efforts consisted of cleaning the cones of trash, often with the assistance of local Boy Scouts in the absence of enough personnel. [49] In the fall of 1954 a formal trail was laid around the Spatter Cones, but most visitors still roamed the cones at will. Not until the early 1960s does any discussion of corrective measures surface in monument records. [50]

In the wake of Mission 66's improvements to the monument's resource management, Superintendent Merle Stitt, as he had at Devil's Sewer, identified the Spatter Cones as a high priority for protection, stating that "Collective damage to spatter cone formations over the period prior to and subsequent to the establishment of the Monument has reached serious proportions." To remedy the situation, Stitt embarked on a study to address corrective action, and in January the following year, the monument submitted its first report on human erosion of the Spatter Cones to the director of Western Region. Yet the record is quiet as to any response by the regional office.

Without any formal program in place, management efforts remained sporadic. For safety, Superintendent Davis installed a grate over Crystal Fissure in 1963, and the following May, the monument once again enlisted the assistance of a Boy Scout troop to obliterate social trails from the slopes of the cones. [51] In September 1965, Superintendent Roger Contor initiated another study to protect the Spatter Cones. Contor, making no mention of the previous report, and implying that the problem had not been resolved, noted that the "present trail system and visitor flow pattern is causing adverse use...." [52] In his 1966 resource management plan, he urged a program to control visitor use and restore the features to a more pristine state. Rehabilitation of social trails, largely responsible for erosion, had failed to mitigate the problem. Hence, Contor decided that a "series of paved, fenced trails and unobtrusive barriers appears to be the only solution." [53]

When Superintendent Paul Fritz arrived only metal handrails enclosed the cones and served as protective devices. Although Fritz planned to complete the improvements recommended by Contor, only "stop-gap" measures resulted--the erection of more handrails and chain-link fencing for safety reasons, and the reconstruction of shoulder material on social trails to combat erosion, in addition to general enforcement and interpretive programs. [54] Yet these were not enough. Upon his arrival at the monument in 1974, Superintendent Robert Hentges underscored the deteriorating condition of the Spatter Cones in his reports and like his predecessors emphasized the cones as a primary target for resource management. The trail networks on the precipitous slopes tainted the aesthetic experience, and contributed to the cones' deterioration. Rocks thrown in the throats of the vents had decreased the depth of the volcanic wells so much that winter snows and ice were melting at a faster pace--all because certain park visitors get enjoyment out of "chucking things down into holes in the ground." [55]

Once more delays emerged to stall any action. Unsure about funding, Hentges did not submit a Development Study Package Proposal (10-238) to rehabilitate the spatter cones site until 1979. The project was intended to balance preservation and use; it would "provide a safe trail system" in order to "insure minimal impact and still allow the visitor to safely experience the spatter cones." [56] As the monument awaited funding, the site nearly reached "the point of irreversible resource destruction." [57] In the meantime, the monument depended on existing procedures and an extensive public information campaign to inform visitors and solicit their support in mitigating impacts. [58]

Rehabilitation began in 1982. The project's major objective, ringing of suggestions voiced over the past three decades, was to improve the aesthetic and natural qualities of the features. Using historic photographs monument managers determined the cones' pristine state with their present state, and determined what an appropriate rehabilitation of the landscape should seek to achieve. Overall, rehabilitation the program rehabilitated all cones, yet only Snow Cone and the second cone were left open to public use, making them the exemplary features of the chain--a decision, Hentges believed, which best met the monument's and agency's mission. [59] Both monument staff and a five-member Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) crew engaged in the labor-intensive program. Workers reshaped the Spatter Cones, hauling cinders and lava rocks from the base of the cones back up to their rims and sides. They upgraded existing foot trails, two of which were obliterated along with more than a thousand feet of social trails. Similarly, they rehabilitated around two thousand square feet of compacted land at the base of cones. About two hundred feet of asphalt trail was improved by the addition of a concrete retaining wall, and steps up to the mouth of the main vent were constructed. The metal handrails, considered unsightly around the first two cones, were replaced with wood railing.

By end of this phase of the project, paved and unpaved trails led up to and around the two open cones. On the second cone the main trail had been rerouted to run along the eastern face of the vent, and trails running the length of the chain had been closed, restricting visitors to designated and signed trails. A new wayside explained the resource management problem and fragility of the Spatter Cones, and the park newspaper and other pamphlets carried a similar message. [60] In August 1985, Superintendent Robert Scott pronounced the spatter cones project "an unqualified success." He noted that "Not only were the geological features rehabilitated, but visual impact in the area was significantly reduced and the visitor can visit the area safely." [61]

Smaller rehabilitation projects were completed in 1987. These involved hard-surfacing approximately 120 feet of trail leading into the second spatter cone, replacing the handrails at the Snow Cone with a sturdier railing designed in an environmentally sensitive manner, and transplanting native vegetation near the parking lot's southern edge as a method to channel foot traffic into the trail system. [62] At present the standard operating procedures at the site include monitoring trails, educating the public through interpretation and signs, and maintaining the trails. All of this helps to protect the cones and ensure visitor enjoyment and safety. Even so, the spatter cones, in spite of the rehabilitation efforts to date, still receive noticeable impacts due to their immense popularity, fragility, and accessibility. [63]

|

| The Spatter Cones as they appeared in 1924. (Haynes Foundation Collection, Montana State Historical Society) |

|

| The Spatter Cones receiving heavy visitation in the 1950s. Note the braided trails on the slopes. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

|

| The Spatter Cones after undergoing trail maintenance in the early 1970s. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

|

|

The Spatter Cones after intensive remediation, mid-1980s.

(CRMO Museum Collection) |

Inferno Cone

Situated near the Crystal Fissure Spatter Cones, Inferno Cone is a cinder cone, a conical mound formed by the accumulation of volcanic cinders around a vent erupting along the Great Rift. Although Inferno Cone is one of twenty-five cinder cones within the monument, its major significance lies in its use as a viewing platform: the panorama of geologic diversity seen from its crest is impressive. The landscape one scans embraces a series of mountain ranges northeast and west of the monument, the surrounding Snake River Plain, and the chain of volcanic features lining the Great Rift. In addition, the clarity of the monument's Class I airshed can be experienced here as well, a common sight being Big Southern Butte, a national natural landmark lying some twenty-five miles southeast of the monument. [64]

Inferno Cone also represents another example of preservation and use at the monument. As visitors trample up the cone's slope to view the feature and the surrounding region, they cause the trail leading up the cone's southwest face to suffer from compaction, widening, and discoloration. One of the most vexing questions for administrators has been the origin of the trail itself. More than likely, the trail formed out of social or casual use in the early 1920s when the loop drive was first bladed through the area. Subsequent management plans of the 1960s and 1970s call out the feature's use as a vista, but do not stress any type of resource management problem. One management plan even expressed that the cone was not the optimum choice for an overlook and proposed Sunset Cone in the northern unit as an alternative. On the other hand, the interpretive program contributed to Inferno Cone's increased use by including it in nature walks in the 1970s. [65]

The problems with the Inferno Cone trail, in this respect, represent a more recent issue for management. In the early 1980s, the monument initiated a program to control the trail widening process occurring with visitor use and to minimize the extent of the compaction and discoloration. At that time, the unmarked trail could accommodate several hikers walking abreast and was wide enough to entice operators of four-wheel drive vehicles to forego the formality of the short hike and drive to the summit.

Robert Hentges and his staff thus undertook two mitigation programs: break-up the trail edges, and better define the trail route. During 1983, the monument employed YCC labor to manually spade and dig up the existing trail. The crew decreased the trail to about ten feet in width. As Hentges recalled, this worked out "beautifully, but of course, by the end of the year it hedged back out three more feet." The next step involved a tractor and a harrow driven up and down the trail to tear up the compacted tread. Visual disturbance formed an early drawback of this method. In contrast to the black cinder surface, the lava is "a nice bright color when you go under," Hentges noted, "but one day its matches out perfect. So [we] just harrowed, you know, with the old spikes, and ripped it up. And that did it." [66] The compaction was diminished, the trail narrowed, and the discoloration alleviated. Apparently, the trail marking program was never implemented, due to the fact that hikers would continue to walk around the lava rocks demarcating the edges.

Although somewhat successful, one management solution led to another problem. Inferno Cone, for example, received greater use as a result of restrictions imposed on the Spatter Cones during their rehabilitation and their restricted access following the project. Having tilled the trail for several years, the monument discontinued that approach in 1985--at the insistence of regional office staff during an operations evaluation. Responding to the evaluation team's recommendations, Superintendent Robert Scott launched a five-year monitoring program to document the trail's compaction, erosion, and widening. [67] Data collected would be used to determine the nature of the problem and whether or not surface erosion would continue after compaction had occurred. The program also called for measuring the trail each fall and for comparing those findings with stakes marking previous widths. [68]

The program turned out to be a failure. During the first year, wooden stakes were either destroyed or lost; new stakes were planted and read the next year, but were stolen by visitors the following season. By the fourth year, managers used buried metal stakes and lost half of them, and in the fifth year, using a metal detector, came up with the same results. In 1989, the monument terminated the monitoring program. Managers felt that the impacts were obvious and explored management options, but these are somewhat controversial, raising the question of aesthetics and resource protection. The point is whether use of the trail should continue, and with it the growing scar visible throughout the monument, or whether some alternative be sought. [69]

As the most recent resource management plan states, one proposal would close Inferno Cone trail altogether and construct another to the top of Big Craters to allow visitors a similar vantage point of the landscape. This would eliminate further erosion of the existing trail, but it is doubtful whether an intensive and possibly expensive rehabilitation program could fully eradicate the trail, or for that matter keep visitors off the closed trail. Furthermore, creating another trail, it is thought, would only multiply resource damage. The proposed trail to the rim of Big Craters, for example, had been tried before in the late 1960s and early 1970s as an interpretive vista, but was later closed due to erosion problems--visitors often climbed down the crater wall to reach the parking lot instead of returning by the trail. Similarly, another proposal suggests relocating the Inferno Cone trail, constructed as a switchback, to the cinder cone's leeward side, which would also require development of a new parking area. Whatever conclusions are reached, any solution places the fragile lava terrain in some kind of jeopardy, and places monument managers in the position of determining an acceptable balance between preservation and use. [70]

Tree Molds

Tree molds are generally found in the monument's remote wilderness backcountry, yet from the end of the spur road south of Inferno Cone, a short trail provides easy access to some of these features. Formed when molten lava flows encased trees and then hardened, tree molds are the cylindrical casts of trees that have burned and rotted away. Vertical and horizontal, the features are delicate, as made clear by Robert Zink's report in the early 1950s, when he discovered the damage to one of the molds at the hands of irresponsible collectors. At one point, Superintendent Roger Contor thought of using plexiglass domes to protect those features exposed to visitor contact. [71] After 1970, wilderness status ensured restricted development and use. While the percentage of visitors who hike into the wilderness is substantially smaller than those who venture into easily accessible sites, the fragile tree molds remain highly susceptible to impairment. Even though only one sign marks their presence, the most vulnerable are those representative tree molds located a mere one mile hike from the road and confined to a small area. [72]

Caves Area

Caves, in the form of pahoehoe lava tubes, spatter cone vents, and fissure caves, are found throughout the monument. They are a significant feature of Craters of the Moon, and are specifically identified in the unit's enabling legislation as being important for their "scientific value and general interest." However, no formal management plan for the caves exists. Reasons for this stem from the usual lack of funding and personnel to patrol these extensive features; management requirements vary from cave to cave, because of their differences in origin, length, size, and accessibility. And until recently, it was thought that unlike many of the other features in the monument, the caves possess "no truly unique or fragile resources that dictate special management needs." [73] Except for the popular developed caves site, most caves are remote and this factor governs their management as wilderness, in or outside the wilderness area's boundary, in that they are generally left alone and unadvertised.

Furthermore, management policies emphasize visitor safety in the caves through interpretive programs, visitor contacts, and, in some instances, facility developments. Over the years, the issue of cave safety has sustained considerable concern in the subterranean environment where visitors encounter unstable rock formations, ice, total darkness, uneven surface areas, and low heights, and, in most cases, require some type of technical assistance for cave exploration, such as flashlights or ropes. Minor injuries and the administration of first aid to visitors are common occurrences associated with the caves.

With the appearance of the 1982 resource management plan, though, the monument identified for the first time, the need for a cave management plan. This grew out of the belief that the monument had fallen short of its enabling mandate to protect its caves, coupled with the recent Park Service initiative to develop a comprehensive resource inventory. Thus the plan noted that the monument needed to detail "specific management programs for individual cave sites. These management programs will vary according to the resource needs and use classifications of each cave." [74]

While such a plan has yet to be drafted, the monument has established some formal policies for the caves. Generally speaking, managers consider caves in the same realm as archaeological resources, and except for certain representative sites, discourage entry. Except for some sites in the frontcountry, managers strive to preserve and protect the caves in their natural state, especially their water sources and wildlife.

Conversely, the "developed" caves region along the loop drive is one of the most popular areas of the monument. Paved and marked trails extend from the parking area to easily accessible caves (Dewdrop, Surprise, Beauty, Boy Scout, and Indian Tunnel) that require neither special equipment nor training to enter and explore. Only the longest tube, Indian Tunnel, has received any significant development, however, through interpretive signs, a marked walking route, and a metal stairway for access; natural light enables visitors to explore its inner reaches without artificial light. The other caves, while open to visitation, have been left undeveloped and they require a light source. Management of the area requires more time and energy, accomplished through interpretive programs (daily guided walks and self-guiding tours throughout the summer), and daily ranger and cleanup patrols.

As exhibited by the management of Indian Tunnel, cave developments were implemented with visitor use and safety in mind. For example, both Arco Tunnel and Great Owl Cavern were outfitted with various types of ladders, and stairs made from rope, chain, wood and metal; [75] the progression toward more stable structures was made for safety reasons after 1934. Access to Arco Tunnel degraded resources, mostly through vandalism, and led to the installation of a wire gate in May 1961. From that period forward the lava tube was accessible only by registration and special-use permit, and was a site for occasional research. [76]

While the gate continues to work well at controlling entry, damage through vandalism has resurfaced periodically over the past twenty years, requiring gate repair and the volunteer efforts still persists at the site. To care for the site, the monument has relied on members of the Gem State Grotto, a local spelunking club, who in 1983 volunteered their time to clean the florescent-orange graffiti arrows from the tunnel's walls and install a new security gate at its mouth. Unfortunately, no solution compatible with the resource has been found to remove the glowing arrows. [77] In contrast to the high-use site, Great Owl Cavern's stairway was removed in 1972, in compliance with wilderness regulations, and is now accessible only by rope or ladder. As with other remote caves, managers discourage exploration of the site since it requires technical climbing, and the repelling equipment can damage the cave itself. Not signed, it has in a sense faded from existence.

Whereas the remoteness of many caves lends itself well to ensuring their preservation, pressures on cave resources have become more acute in recent years. Managers, although discouraging cave exploration, were obligated to divulge the location of caves through the Freedom of Information Act. Maps also documented their location, exposing caves to more threats. One significant example has arisen over the exploration of Crystal Pit. Because the crystals are extremely fragile and the pit is extremely deep, requiring technical climbing, the cave has been closed to public access since August 1963. But it appears from damage to the grate that Crystal Pit has been entered over the years, and within the last few years, a group of cave enthusiasts has filed an official protest to explore the site. Furthermore, research has documented at least two rare species living in the monument's caves, the Blind Cave Beetle and the Townsend Bat.

With the passage of the Federal Caves Resources Act Protection Act in 1988, which mandates the study of cave resources and the identification of significant caves, managers received further impetus to complete a cave inventory and management plan. By doing so, they can address these and other issues. The legislation itself provides management assistance. It officially places caves in the category of archaeological sites, for instance, enabling managers to withhold information from the public except under specific conditions. For this reason especially, the monument proceeded with an inventory and management plan. [78] Relying on volunteer labor over a period of several years, since there was neither funding nor personnel to conduct such an extensive study, the monument hoped to have its plan drafted by 1992. [79]

VEGETATION

Although the volcanic landscape of Craters of the Moon appears to be a trackless waste, it supports a wide array of plant life. The monument's lava flows contain twenty-six vegetation types and over three hundred plant species. Cinder cones, the Carey Kipuka, and the northern unit, for example, sustain various plant communities of lichens, grassses, herbs, shrubs, and trees. Management issues have revolved largely around the control of trespass grazing in the north end, to a lesser extent, control of exotic species, fire ecology, and protection and study of the Carey Kipuka.

GRAZING

By far the most protracted issue, trespass grazing, mostly by sheep, has plagued monument managers nearly from the area's inception. The place of contention lies in the foothills of the Pioneer Mountains in the north unit; this environment possesses Little Cottonwood Creek drainage (source of the monument's administrative water supply), traditional grazing lands, and lush vegetation: native grasses, Douglas fir, aspen, and other riparian plant life. The monument did not inherit the grazing problem upon its establishment. The original legislation included only what might be termed "worthless" grazing lands south of the foothill country. But with the enlargement of the monument in July 1928, Craters of the Moon acquired more than two thousand acres of hill country for its administrative water supply and with this lands grazed by livestock. And so began a long history of mitigation policies for trespass grazing.

Roots of Controversy

Expansion, among other things, incorporated the Little Cottonwood Creek drainage to secure an administrative water supply. The grazing issue was connected generally with this expansion and specifically with the water system land exchange. The monument's enlargement and the resolution of private holdings incited protests from some livestock interests who questioned the intentions of the Park Service and its encroachment on the "public domain," and more important, its policy regarding grazing in the new area. Throughout the settlement of private claims in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the controversy boiled down to clarifying the Park Service's grazing policy at Craters of the Moon, specifically in the northern unit.

A major source for the controversy has been the boundary. As the management of the mule deer herd and poaching demonstrates, the northern boundary was not drawn to conform to topography but rather the grid pattern of township and range. Instead of following the hydrographic divide--or ridgelines--and therefore being readily apparent, the border runs a seemingly arbitrary course up and down the northern slopes. This poses a particular problem for the prevention of livestock grazing, since sheep and cattle unless restrained by attentive herders or sturdy fences will roam at will in search of greener pastures. Due to the boundary and the fact that federally administered and privately owned grazing lands abut the monument, trespass occurs. The Park Service boundary invited this type of controversy because the lands involved were at one time part of the open range and also part of a seasonal sheep migration route.

The First Grazing Policy: The Stock Drive Path

On October 5, 1929, Custodian Robert Moore notified the Washington office that stockmen had used the grass on Sunset and Grassy Cones prior to the monument's 1928 expansion, and had "trailed through that way" for years driving their sheep from winter to summer range and points of shipment in the Wood and Lost River regions. Because of this precedent, Moore recommended that the Park Service designate a driveway to accommodate this activity, covering virtually the entire northern unit. [80]

Amenable to Moore's suggestion, the Park Service responded on October 24 stating that it was willing to make an exception to its general policy of grazing prohibition in national monuments and parks "in view of the conditions at Craters of the Moon there would appear to be no objection to permitting sheep men to drive their flocks through the monument area, though it would be unwise to permit them to graze on Grassy and Sunset Cones and other areas while en route." [81] The one requirement was that all stockmen receive prior permission and that the stock move through "uninterrupted."