Historical Background

SINCE 1787 the Constitution has been considerably

modified to perfect, amplify, and keep it abreast of changing times. The

main mechanisms have been amendments and judicial interpretation. The

amending process is outlined in Article V of the Constitution.

Amendments may be proposed to the States either by Congress, based on a

two-thirds vote in both Houses; or by a convention called by Congress at

the request of the legislatures of two-thirds of the States.

Ratification requires the approval of three-fourths of the States,

either by their legislatures or special conventions as Congress may

direct. No national constitutional convention has ever been called, and

the only amendment ratified by special State convention was the

21st.

|

| All along the route, the populace paid tribute to George Washington as he traveled from Mount Vernon to his inauguration in New York City. Here is an artist's depiction of the salute he received in New York Harbor. (Oil (late 19th century) by L. M. Cooke. National Gallery of Art.) |

The number of amendments to date totals 26, the first 10 of which (Bill of Rights) were enacted shortly after ratification of the original document. When this volume went to press, another had been passed by Congress and was being actively considered by the States. Those that have been accepted have survived a grueling process. Thousands of proposals for amendments of all sorts—praiseworthy and frivolous, realistic and impractical, even including suggestions for a virtually new Constitution—have been recommended over the years by Congressmen, political scientists, and others. But these have either failed to win the favor of Congress or the States.

|

| Washington's inauguration on the balcony of Federal Hall, New York City, April 30, 1789. This is the only known contemporary rendition of the event. (Engraving (ca. 1790) by Amos Doolittle, after a drawing by Peter Lacour. J. N. Phelps Stokes Collection, New York Public Library) |

Of the successful amendments, some, reflecting changing national aspirations and mores as well as fundamental social transformations, have produced governmental reforms and social changes. Others have refined the constitutional structure for such purposes as democratizing the political system, improving its functioning, or relieving associated abuses. The first 10 amendments came into being because of fear of national governmental tyranny.

Except for the Bill of Rights, until the last half-century amendments have been relatively rare. For 122 years after 1791, when the Bill of Rights was adopted, only five (two in the early years of the Republic and three in the aftermath of the Civil War) were enacted—or an average of one about every 25 years. Since 1913, on the other hand, the Nation has approved 11, or one every 5-1/2 years or so. The increased frequency in recent times is doubtless to a considerable extent attributable to the rapidity of social and economic change.

From the beginning regarded as virtually a part of the original Constitution, the Bill of Rights was mainly designed to prevent the Federal Government from infringing on the basic rights of citizens and the States. Essentially a reassertion of the traditional rights of Englishmen as modified and strengthened by the American experience, these measures had already been delineated in various forms—in the Northwest Ordinance of 1787; the declarations, or bills, of rights that had been adopted by most States, either separately or as part of their constitutions; the Declaration of Independence (1776); the Declaration of Rights that the First Continental Congress had issued in 1774; and early colonial manifestoes.

During the Constitutional Convention and the ratification struggle in the States, many objections had been made to the exclusion from the Constitution of similar guarantees. When ratifying, many States expressed reservations and suggested numerous amendments, especially a bill of rights. North Carolina, decrying the absence of a declaration of rights in the Constitution, even refused to ratify in 1788 and did not do so until the following year, after the new Government had been established and by which time such provisions had been proposed for addition to the instrument.

Washington called attention to the lack of a bill of rights in his Inaugural Address, and the First Congress moved quickly to correct this fault. Madison, in a prodigious effort, synthesized most of the amendments the States had recommended into nine propositions. The House committee, on which he sat, expanded these to 17. The Senate, with House concurrence, later reduced the number to 12. Meantime, the decision had been made to append all amendments to the Constitution rather than to insert them in the text at appropriate spots, as Madison had originally desired.

By December 1791 the States had ratified the last 10 of the 12 amendments, which the Congress had submitted to them in September 1789. The first of the two that were not sanctioned proposed a future change in the numerical constituency of Representatives and in their number; the second would have deferred any changes in congressional salaries that might be made until the term of the succeeding Congress.

The first amendment, covering the free expression of opinion, prohibits congressional interference with the freedom of religion, speech, press, assembly, and petition. Amendments two through four guarantee the rights of citizens to bear arms for lawful purposes, disallow the quartering of troops in private homes without the consent of the owner, and bar unreasonable searches and seizures by the Government.

Amendments five, six, and eight essentially provide protection against arbitrary arrest, trial, and punishment, principally in Federal criminal cases though over the course of time the judiciary has held that many of the provisions also apply in State cases. Mainly to prevent harassment of the citizenry by governmental officials, these measures establish the right of civilian defendants to grand jury indictments for major crimes; prohibit "double jeopardy," or duplicate trial, for the same offense, as well as self-incrimination; deny deprivation of "life, liberty, or property without due process of law"; insure the right of the accused to have legal counsel, be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation, subpoena witnesses on his own behalf, confront the witnesses against him, and to receive an expeditious and public jury trial; and ban excessive bails and fines, as well as "cruel and unusual punishments." The fifth amendment also prohibits the Government seizure of private property under the doctrine of eminent domain without proper compensation.

The seventh amendment guarantees the right of a jury trial in virtually all civil cases.

Amendment nine states that the rights enumerated in the Constitution are not to be "construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The 10th amendment, somewhat different from the other nine because of its allusion to the States, reserves to them and the people all "powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States."

Contrary to a popular misconception, the main body of the Constitution also contains various safeguards similar to those in the Bill of Rights that protect citizens and the States against unreasonable actions. Article I prohibits the Government from suspending the writ of habeas corpus, which would otherwise allow arbitrary arrest; and both the national Government and the States from enacting bills of attainder (legislative punishment of crimes) and ex post facto laws (retroactively making acts criminal). Article III requires a jury trial for Federal crimes, and limits the definition of treason and penalties for the offense.

Article IV guarantees that the acts, records, and judicial proceedings of one State are valid in all the others; grants to citizens of every State the privileges and immunities of the others as defined by law; warrants the representative government and territorial integrity of the States; and promises them the protection of the national Government against foreign invasion and domestic insurrection. Article VI excludes religious tests for officeholding.

Nevertheless, it is the Bill of Rights that has become the main bulwark of the civil liberties of the American people. These measures, which make the Constitution a defender of liberty as well as an instrument of governmental power, represented another swing of the pendulum. The Articles of Confederation had created a weak league of semi-independent States. As a result, citizens looked primarily to the States for protection of their basic rights, which were defined in constitutions or separate declarations. Then, the Constitution provided a strong central Government. This was counterbalanced by the Bill of Rights, which allowed continuance of such a Government with full regard for the rights of the people.

In recent decades, the Bill of Rights has acquired increased significance to all citizens because the Supreme Court has ruled that many portions of it are applicable to the States as well as to the Federal Government.

|

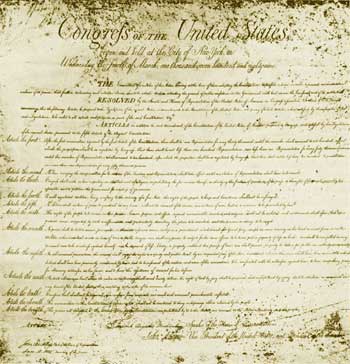

| The Bill of Rights. (National Archives.) |

The 11th amendment, which was passed by Congress in 1794 and ratified the next year, was engendered by State objections to the power of the Federal judiciary and represents the only occasion to date whereby an amendment has limited its authority. Curtailing Federal power in actions brought against individual States, the measure denies the Federal courts jurisdiction over private suits brought against one State by citizens of another or of a foreign country.

The 12th amendment, which won the approbation of Congress in 1803 and State approval the following year, is a constitutional accommodation to the formation of political parties. Many of the Founding Fathers, who had themselves not been immune to divisiveness, had feared their growth, which they believed would stimulate factional strife. But parties soon proved to be necessary vehicles for the Nation's political life.

As they grew, the method of electing the President and Vice President as originally set forth at Philadelphia became cumbersome and controversial, if not practically unworkable. The election of 1796 produced a President and Vice President of different parties. In 1800 a tied electoral vote occurred between members of the same party, and the House of Representatives was forced to choose a President. These two experiences created the necessary sentiment to modify the electoral process. The principal provision of the 12th amendment required future electors to cast separate ballots for the two executives.

For more than six decades after the ratification of the 12th, no further amendments were enacted. Then the Civil War crisis created three, the so-called "national supremacy" amendments, which congressional Radical Reconstructionists proposed. The 13th, sent out to the States in 1864 and ratified in 1865, was the first attempt to use the amending process to institute national social reform. It followed upon Lincoln's limited and preliminary action in the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) to free the slaves. Although the amendment declared slavery and involuntary servitude (except as punishment for crimes) to be unconstitution al,it did not provide blacks with civil-rights guarantees equal to those of whites.

During the Reconstruction Period, therefore, two more additions to the Constitution became the law of the land. Their main objectives were to insure the rights of black men to full citizenship. Ultimately, however, because of their broad phraseology, the two amendments have come to have significant repercussions for all citizens. The 14th, proposed in 1866 and ratified 2 years later, decrees that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are citizens of the Nation and of the State in which they live. The legislation also forbids the States from making any laws that abridge the "privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States," deprive them of "life, liberty, or property, without due process of law," or deny them the "equal protection of the laws."

The amendment also expanded representation in the House of Representatives from that contained in the original Constitution (the free, essentially white, population plus three-fifths of all slaves) to include all persons except untaxed Indians. Another provision stated that the representation of States arbitrarily denying the vote to adult men would be reduced. The measure also barred from Federal officeholding those Confederates who had held Federal or State offices before the Civil War, except when Congress chose to waive this disqualification; and ruled invalid all debts contracted to aid the Confederacy as well as claims for compensation covering the loss or emancipation of slaves.

The most important goal for which the amendment was added to the Constitution, the legal equality of blacks, was not fully realized until the 24th outlawed the poll tax in 1964. The attempt to limit the political participation of ex-Confederate leaders failed. In recent years, however, the Supreme Court has often used the amendment to achieve fuller State conformance with the Bill of Rights. Furthermore, judicial interpretations have broadened the meaning of such key phrases as "privileges or immunities", "due process," and "equal protection of the laws." Congress has also passed new enforcement legislation.

Despite the legislative efforts of the Radical Republicans, black men continued to be denied equal voting rights. In 1869, therefore, Congress passed and the next year the States ratified the 15th amendment. Attempting to protect the rights of ex-slaves it explicitly stated: "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

Not until 1913 was the Constitution again changed. Prior to that time, Congress had only enjoyed the power to levy direct taxes in proportion to the populations of the States. During the late 19th century, the need for a Federal income tax began to become apparent to many people in the country, but the Supreme Court on various occasions declared such a tax to be unconstitutional. By 1909 support for it was strong enough to warrant passage of the 16th amendment. Many Congressmen who voted affirmatively felt the States would never approve the action. Yet, 4 years later, they ratified it. The income tax quickly became a principal source of Federal revenue and facilitated governmental expansion.

|

| Women's suffrage parades, such as this one in Washington, helped pave the way for the 19th amendment (1919). (Library of Congress (Harris & Ewing).) |

Later in 1913 the States approved another amendment, which Congress had sanctioned the previous year. The 17th authorized the direct election of Senators by the voters rather than by State legislatures, as specified in the Constitution. The original method had long been a target of reformers. Numerous times between 1893 and 1911 the House of Representatives proposed amendments calling for popular selection of Senators. The Senate, however, apparently concerned among other things about the tenure of its Members and resenting the invasion of their prerogatives by the lower House, refused to give its stamp of approval to the legislation. But, by the latter year, pressure for change had become intense, particularly because the popular image of the Senate had become that of a millionaires' club divorced from the interests of the people. That same year, an Illinois election scandal helped turn the tide. Also, many States had by that time adopted senatorial preference primaries as an expression of popular sentiment to the legislators.

The highly controversial "prohibition" amendment, the 18th, cleared Congress in 1917 and was ratified 2 years hence. It prohibited the "manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes" and their importation into or exportation from the United States. This legislation was the result of nearly a century of temperance efforts to eliminate or limit use of alcoholic beverages. But unsuccessful enforcement and opposition by large elements of the public, particularly in urban areas soon doomed the "noble experiment." In the only instance when an amendment has been repealed by another, the 21st, which was both proposed and ratified in 1933, voided the 18th. It returned control of alcohol consumption to States and local jurisdictions, which could choose to remain "dry" if they so preferred.

|

| Public concern over the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, whose funeral cortege is shown leaving the Capitol, and the extended sicknesses of Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Dwight D. Eisenhower influenced passage of the 25th amendment (1967). (Library of Congress (Abbie Rowe).) |

The persistence of reformers likewise produced the 19th amendment, passed in 1919 and ratified the next year. Equal voting rights in Federal and State elections were granted to women. Especially after the Civil War, they had begun to improve their legal status, and some States in the West had granted them the right to vote. During the early years of the 20th century, more States extended the privilege. These and other factors, coupled with the efforts of suffragists, facilitated adoption of the amendment. It marked a major step toward fuller political equality for women.

Congress gave its imprimatur to the so-called "lame duck" amendment, the 20th, in 1932 and it became effective the next year. Designed mainly to hasten and smooth the post-election succession of the President and Congress, it specified that the terms of the President and Vice President would begin on January 20 following the fall elections instead of on March 4 and required Congress to convene on January 3, when the terms of all newly elected Congressmen were also to begin. Correcting another defect in the Constitution was the stipulation that the Vice President-elect would succeed to the highest office in the land in the event the President-elect died before his inauguration or no President-elect had qualified.

Proposed to the States by Congress in 1947, the 22d amendment was ratified in 1951. Aimed in large part at preventing the repetition of the unprecedented four terms to which Franklin D. Roosevelt had been elected as President, it limited the service of Chief Executives to a maximum of the traditional two full terms. Vice Presidents succeeding to the office were to be restricted to one term if the unexpired portion of that to which they succeeded was longer than 2 years. The incumbent, Harry S Truman, who was serving when this amendment was added to the Constitution, was exempted from it, though he did not choose to run for a second full term.

District of Columbia residents won the right to vote for Presidential electors in the 23d amendment, which gained congressional approval in 1960 and was ratified the following year. It was part of the endeavor to obtain for D.C. residents political rights equal to those of citizens of the States. Although this step fell short of the "home rule" sought for the District, it was a major step toward more extensive political participation by its citizens.

|

| Last page of General Services Administration proclamation declaring the 25th amendment to be in effect. (National Archives.) |

The civil-rights struggle of black people in the 1950's and early 1960's resulted in the 24th amendment, which was proposed in 1962 and ratified 2 years later. It outlawed poll taxes as a prerequisite for voting in Federal elections. This device had long been used in some places to limit political participation, especially by blacks.

The long illnesses of Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Dwight D. Eisenhower and the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, coupled with the enormous contemporary importance of the Presidency, gave rise to the 25th amendment. It was passed by Congress in 1965 and ratified in 1967. Steps to be followed in the event of Presidential disability were outlined, and a method was established for expeditiously filling vacancies in the office of Vice President. When there is no Vice President, the President will nominate a replacement, who needs only approval by a congressional majority. In the event of Presidential disability, the Vice President will temporarily hold the office of Acting President.

|

| The 100th anniversary of the Constitution occasioned celebrations across the land and such special tributes as a "Centennial March." (Library of Congress.) |

The 26th amendment, proposed and ratified in 1971, provided another extension of the franchise. In recognition of the increasing contributions of youth to American society, the minimum voting age in all elections was lowered to at least 18 years. Although a few States, in accordance with their discretionary rights at the time, had earlier reduced the voting age from 21, this constitutional addition made the national franchise uniform in terms of minimum age.

When this volume went to press, another amendment, which would ban discrimination based on sex (the "equal rights" amendment), had been proposed to the States, in 1972, but all the required 38 States had not yet ratified it.

DESPITE its numerous advantages, the amendment

process has proven to be less than perfect as a vehicle of change.

Although the rigorous procedure required to enact amendments has

prevented hasty and ill-advised action, it has on occasion delayed the

inauguration of badly needed reforms. The brief and sometimes imprecise

wording of the amendments, as well as of the Constitution itself, has

necessitated prolonged and complex interpretation by the Supreme Court.

The public and various governmental organs have on occasion failed to

heed or fully execute our highest national law.

|

| "We the People," theme painting and official poster of the Constitution Sesquicentennial Celebration, as rendered by Howard Chandler Christy. (National Archives.) |

Whatever the flaws in our constitutional system, it enunciates our democratic principles and provides a superlative formula and instrument of Government, which has established its primacy among the efforts of men to govern themselves. Yet the true guardian of our sacred charter of liberties is the vigilance of the people.

|

|

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/constitution/introj.htm

Last Updated: 29-Jul-2004