.gif)

MENU

Selected Constitutional Decisions

Existing National Historic Landmarks

NOMINATIONS

First Bank of the United States

Pittsylvania County Courthouse

Second Bank of the United States

|

The U.S. Constitution

First Bank of the United States |

|

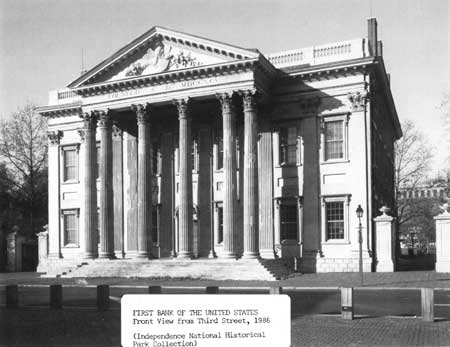

First Bank of the United States, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

(Independence National Historical Park Collection)

| Name: | First Bank of the United States |

| Location: | 116 South Third Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Owner: | Independence National Historical Park |

| Condition: | Excellent, altered, original site |

| Period: | 1700-1799 |

| Areas of Significance: | architecture, economics, law, politics/government, constitutional history |

| Builder/Date: | Samuel Blodgett, 1797 |

DESCRIPTION

The First Bank of the United States—originally called the Bank of the United States—operated from 1797-1811, on Third Street, midway between Chestnut and Walnut streets. Samuel Blodgett, Jr., merchant, author, publicist, promoter, architect, and "Superintendent of Buildings" for the new capital in Washington, DC, designed the building in 1794. 1 At its completion in 1797, the bank won wide acclaim as an architectural master piece. By today's standards the building remains a notable early example of Classical monumental design.

The bank is a three-story brick structure with a marble front and trim. It measures 90' 11" across the front by 81' 9". Its seven-bay marble facade, with the large 48' x 11' Corinthian hexastyle portico, is the work of Claudius F. LeGrand and Sons, stone workers, woodcarvers and guilders. The remarkably intact portico tympanum, restored in 1983, contains elaborate mahogany carvings of a fierce-eyed eagle grasping a shield of thirteen stripes and stars and standing on a globe festooned with an olive branch. The restored hipped roof is covered in copper—some of which, over the portico, is original—and has a balustrade along its four sides.

When the first charter of the Bank of the United States lapsed in 1811, Stephen Girard purchased the building and opened his own bank, Girard Bank, in 1812. Although at Girard's death in 1832 the building was left in trust to the City of Philadelphia, the Girard Bank continued in operation there until 1929, covering a 117-year occupancy. In 1902 the Girard Bank hired James Windrim, architect, to remodel the interior. Windrim removed the original barrel vaulted ceiling and introduced a large skylight over a glass-paned dome to furnish more light for the first floor tellers. He altered the original hipped roof further with the introduction of a shaft tower on the west side of the building for an elevator. Between 1912 and 1916 Girard Bank also constructed a two-story addition on the west facade of the building.

After being vacated in 1929, the bank building languished until the National Park Service purchased it in 1955 as part of Independence National Historical Park. Between 1974 and 1976 the Park restored the building's eighteenth century exterior appearance and retained its 1902 interior remodeling, leaving an 86' x 67' banking room on the first floor and numerous smaller rooms—used as park offices and library space—around its outer perimeter on the second and third floors. The central area is defined by a circular Corinthian columned rotunda on the first and second floors and an electrically lit glass dome at the third floor level. The cellar retains its 1795 stone-walled and brick-vaulted rooms, sane still having their original sheet iron vault doors.

The First Bank of the United States is significant because the institution provoked the first great debate over strict, as opposed to an expansive interpretation of the Constitution. In adopting Hamilton's proposal and chartering the bank both the Congress and the President took the necessary first steps toward implementing a sound fiscal policy that would eventually ensure the survival of the new federal government and the continued growth and prosperity of the United States.

BACKGROUND 2

Hamilton's proposal to charter a national bank was severely attacked in Congress on constitutional grounds. The opposition was led by James Madison, who was becoming increasingly hostile to Hamilton's program. Although the two men had supported strong national government in the convention and had worked together to secure ratification of the Constitution, neither their constitutional philosophies nor their economic interests were harmonious. Hamilton wished to push still further in the direction of a powerful central government, while Madison, now conscious of the economic implications of Hamilton's program and aware of the hostility which the drift toward nationalism had aroused in his own section of the country, favored a middle course between centralization and states' rights.

In the Constitutional Convention Madison had proposed that Congress be empowered to "grant charters of incorporation," but the delegates had rejected his suggestion. In view of this action, he now believed that to assume that the power to incorporate could rightfully be implied either from the power to borrow money or from the "necessary and proper" clause in Article I, Section 8, would be an unwarranted and dangerous precedent.

In February 1791, the bank bill was passed by Congress, but President George Washington, who still considered himself a sort of mediator between conflicting factions, wished to be certain of its constitutionality before signing it. Among others, Thomas Jefferson was asked for his view, which in turn was submitted to Hamilton for rebuttal.

In a strong argument Jefferson advocated the doctrine of strict construction and maintained that the bank bill was unconstitutional. Taking as his premise the Tenth Amendment (which had not yet become a part of the Constitution), he contended that the incorporation of a bank was neither an enumerated power of Congress nor a part of any granted power, and that implied powers were inadmissible.

He further denied that authority to establish a bank could be derived either from the "general welfare" or the "necessary and proper" clause. The constitutional clause granting Congress power to impose taxes for the "general welfare" was not of all-inclusive scope, he said, but was merely a general statement to indicate the sum of the enumerated powers of Congress. In short, the "general welfare" clause did not convey the power to appropriate for the general welfare but merely the right to appropriate pursuant to the enumerated powers of Congress.

With reference to the clause empowering Congress to make all laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution the enumerated powers, Jefferson emphasized the word "necessary," and argued that the means employed to carry out the delegated powers must be indispensable and not merely "convenient." Consequently, the Constitution, he said, restrained Congress "to those means without which the grant of power would be nugatory." In rebuttal, Hamilton presented what was to become the classic exposition of the doctrine of the broad construction of federal powers under the Constitution. He claimed for Congress, in addition to expressly enumerated powers, resultant and implied powers. Resultant powers were those resulting from the powers that had been granted to the government, such as the right of the United States to possess sovereign jurisdiction over conquered territory. Implied powers, upon which Hamilton placed his chief reliance, were those derived from the "necessary and proper" clause. He rejected the doctrine that the Constitution restricted Congress to those means that are absolutely indispensable. According to his interpretation, "necessary often means no more than needful, requisite, incidental, useful, or conducive to.... The degree in which a measure is necessary, can never be a test of the legal right to adopt; that must be a matter of opinion, and can only be a test of expediency."

Then followed Hamilton's famous test for determining the constitutionality of a pro posed act of Congress: "This criterion is the end, to which the measure relates as a mean. If the end be clearly comprehended within any of the specified powers, and if the measure have an obvious relation to that end, and is not forbidden by any particular provision of the Constitution, it may safely be deemed to come within the compass of the national authority." This conception of implied powers was later to be adopted by John Marshall and incorporated in the Supreme Court's opinion in McCulloch v. Maryland (1819) on the constitutionality of the second national bank.

ARCHITECTURAL SIGNIFICANCE 3

The First Bank of the United States is also architecturally significant. Designed by Samuel Blodgett with Joseph P. LeGrand as marble mason, the First Bank was probably the first important building with a classic facade of marble to be erected in the United States. Although somewhat changed by subsequent alterations, the exterior of the building is today essentially as it was in 1795, the date of the earliest drawing and description uncovered so far. Unfortunately, lack of documentation and extensive alterations perpetrated in 1901-02 leaves knowledge of the interior inadequate.

FOOTNOTES

1 Material for the Description was taken from the following source:

Anna Coxe Toogood, "Draft National Register Nomination Independence National Historical Park" (Unpublished Report, Independence National Historical Park, National Park Service, November 5, 1984), no page number.

2 Material for the Statement of Significance was taken from the following source:

Alfred H. Kelley, Winfred A. Harbison and Herman Belz, The American Constitution: Its Origins and Development (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1983), pp. 130-31.

3 Material for the Architectural Statement of Significance was taken from the following source:

John B. Dodd, "Classified Structure Field Inventory Report for the First Bank of the United States" (Unpublished Report, Mid-Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, April 27, 1976), no page number.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Corwin, Edward S. The Constitution And What It Means Today. 13th ed. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1973.

Dodd, John B. Classified Structure Field Inventory Report for the First Bank of the United States. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Mid-Atlantic Regional Office, National Park Service, Unpublished, April 27, 1976.

Fribourg, Majorie G. The Supreme Court in American History. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Macrae Smith Company, 1984.

Kelley, Alfred H.; Harbison, Winfred A.; Belz, Herman. The American Constitution: Its Origins and Development. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1983.

Toogood, Anna Coxe. Draft National Register Nomination Independence National Historical Park. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Independence National Historical Park, Unpublished, November 5, 1984.

Top

Top

Last Modified: Wed, Aug 30 2000 7:00:00 am PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/butowsky2/constitution5.htm

![]()