|

John Jarvie of Brown's Park BLM Cultural Resources Series (Utah: No. 7) |

|

CHAPTER II

BROWN"S PARK 1871-1913: THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE BEAUTIFUL

In his book The Great Salt Lake, Western historian Dale Morgan asked the question "Who shall say whether the thousand existences in quiet do not more nearly express the shape of human experience than the fiercely spotlighted existence that survives as history?" [46] As the Brown's Hole era of the mountain men and explorers gave way to the Brown's Park of cattle ranchers and settlers, the valley became a harbor for "existences in quiet." It became the home for a community of common people seeking their share of the American dream. While many of them were undeniably colorful characters, they were not "fiercely spotlighted" on a national or global scale. Their struggles were personal ones. Their victories and failures did not create noticeable waves beyond the mountains which walled in their world. Their activities, indeed, expressed "the shape of human experience." The few who have become household names, like Butch Cassidy, were not permanent settlers, but rather, temporary visitors who were able to take advantage of the unique harbor offered by Brown's Park; a harbor which was not only geographical but also cultural. It was the result of human nature reacting to physical nature on the frontier.

"Frontiers are not east or west, north or south," said Thoreau, "but wherever a man fronts a fact." [47] The facts fronted by early settlers in Brown's Park were nature, geography, and isolation. Their society was created by their response to those fronts. Isolation and geography had a leveling effect on society. Blacks, Mexicans, and whites interacted to a degree that would have been unthinkable in urban areas of the era. Likewise, wealth did not necessarily guarantee social standing. Rich and poor alike were subjected to the same laws of nature and, thus, competed for survival as equals. Cooperation and mutual interdependence were mandated by the Brown's Park stage. Certainly personality conflicts and rivalries existed but they were reduced to pettiness by the necessities of the physical setting. While the Hoys and the Crouses might maintain a verbal feud, they could always count on mutual assistance in cases of illness or serious crisis. Genteel Southerner Elizabeth Bassett befriended and depended on ex-slave Isom Dart while ferryman and storekeeper John Jarvie occasionally employed known outlaws without fear for life or property. Such seemingly incongruous situations were merely Brown's Park's way of dealing with its physical setting.

Response to its physical situation gave Brown's Park a particular set of mores. The Brown's Park mores, in turn, created a society with a unique outlook on the nature of law. Two major related themes dominated the area from 1871 until 1913: cattle rustling and outlaw sheltering. The permanent residents in Brown's Park, who were considered to be law abiding by their peers, were nearly all cattle rustlers to some degree. Those who were not rustlers were content to allow known law breakers to inhabit their valley periodically. Brown's Park had developed its own code of ethics.

The code of ethics applied equally to the permanent "law abiding rustlers" and the transient outlaws. Both groups developed ethics which fit their situations and rejected those of society which did not. Both had a Robin Hood orientation. The rustlers would acquire stock at the expense of the larger outfits (consequently, approval of rustling diminished as the size of the rustler's own herd grew) and the outlaws would take from the rich (banks and railroads) and give to the poor (themselves). [48] While Brown's Park tolerated thievery, it held life as sacred and would not condone murder. Jack Bennett paid with his life for his association with killers. John Jarvie's murderers, although they escaped, were pursued beyond the Park. Ann Bassett carried out a vendetta against a cattle baron suspected of ordering murder. While Brown's Park existed outside certain definitions of the law, it strictly adhered to its own code of ethics. [49]

Beneath the periodic outbursts of excitement, the "existences in quiet" which made up the majority of the Brown's Park citizenry, continued their unheralded day to day activities which, as Morgan wrote, "express the shape of human experience."

One of the first more or less permanent residents of Brown's Park was Juan Jose Herrera, a native of New Mexico nicknamed "Mexican Joe." Herrera had come to Brown's Park via South Pass, Wyoming, in 1870 with a small group of men intent on starting a cattle business by acquiring a few head from every big outfit that passed through the Park. Herrera and his men settled in the eastern end of the valley. [50]

The next year, 1871, Herrera sent for his attorney friend Asbury B. Conway of South Pass. Conway moved in with the Mexicans and managed to maintain an almost constant state of inebriation. Conway was one of the local boys who made good. He eventually left Brown's Park, entered into a political career in Wyoming and "in the election of state officers held on September 11, 1890, the one time horse thief and cattle rustler was named a justice of the Supreme Court. . .[He] became Chief Justice of the Wyoming Supreme Court in 1897...." [51]

Juan left Brown's Park temporarily in the late 1880s and returned to New Mexico where he organized a group of masked, native night riders known as the White Caps or las Gorras Blancas who resisted Anglo land encroachment in San Miguel county. The group eventually numbered 700 and operated in three counties. Juan and his brother, Pablo, were also active in the Knights of Labor organization in which Juan served as a district organizer. He was "capable of understanding the new ideas and attitudes regarding unions which being generated by the labor unrest of this period. His command of English was excellent. . .he once served as a translator for the New Mexico territorial legislature." [52] Following his days of activism, Juan returned to Brown's Park and lived out his life in relative obscurity.

While the Herrera gang were not outlaws in the traditional sense, another group which frequented Brown's Park during the period definitely was. They were the Tip Gault Gang. Among the gang's number were Tip Gault, Jack Leath, Joe Pease, a Mexican known only as Terresa, and an ex-slave, Ned Huddleston. Huddleston had been born in Arkansas in 1849. After the Civil War, he drifted into Mexico and Texas working as a rodeo clown and eventually arrived in Brown's Park with a cattle drive. One evening the Gault Gang was burying a member who had been kicked to death by a horse when they were ambushed by a group of cowboys seeking revenge for earlier Gault wrong-doings. All of the gang were killed except Huddleston who jumped into the grave and played dead. Ned eventually crawled out of the grave and stole a horse from a nearby ranch to make his getaway. The rancher spotted him and managed to shoot him in the leg as he rode away. Exhausted from the loss of blood, Ned fell off of his horse and passed out on the trail. Miraculously, Ned was discovered and nursed back to health by William "Billy Buck" Tittsworth who, as a youngster in Arkansas, had lived on a plantation neighboring Ned's. The two men had been close friends in their youth and had not seen each other for years before that fateful night on the trail. Huddleston managed to get to Green River City where he caught the first train out of town. He changed his name and determined to go straight. He would eventually return to Brown's Park as Isom Dart. [53]

In 1871, George Baggs wintered a herd of Texas cattle in Brown's Park. Though cattle elsewhere perished during the winter, Baggs did not loose a single one of his nine hundred head. Thus the fame of Brown's Park continued to spread. Baggs sold his herd to Crawford and Thompson in Wyoming and the same cattle were driven back to Brown's Park by Jesse S. Hoy the following winter. Arriving in Brown's Park, Hoy found it already occupied by nearly 4,000 cattle belonging to two Texas outfits run by Asa and Hugh Adair and a Mr. Keiser. The cattle were not as fortunate during the winter of 1872-1873 and at least 500 died before spring. [54]

Hoy, however, was so impressed by the potential of Brown's Park that he encouraged other members of his family to relocate there. His brother Valentine arrived in 1873 along with Sam and George Spicer and about 300 cattle. Adea Hoy and Benjamin Hoy arrived in 1875 and Harry Hoy arrived in 1880. "The Hoys, with family money to invest, had ambitions of setting up a range empire on the Iliff model, but found themselves so hedged in by other outfits and belligerent homesteaders that they had to content themselves with relatively modest spreads." [55]

|

| Photo 7. Parsons' Cabin, Brown's Park first post office. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

|

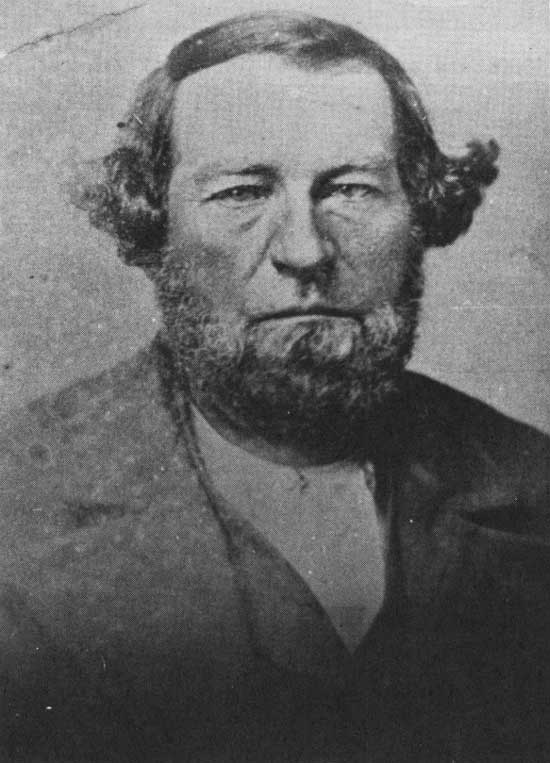

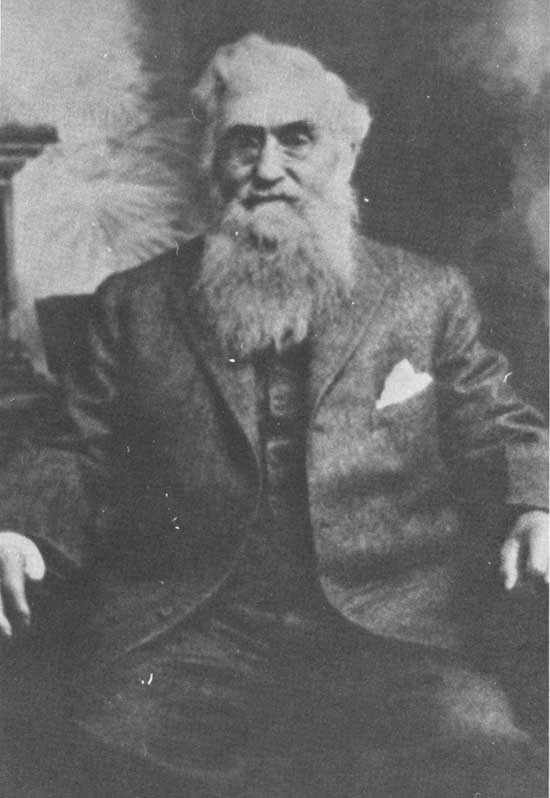

| Photo 8. Dr. John Parsons. (Photo Credit: Gladd Ross Collection). |

Dr. John Parsons (son of Warren Parsons and "Snappin' Annie", the first white woman to enter Brown's Park) brought his family to Brown's Park around 1874. He built a cabin near Sears Creek and a smelter and a forge on the north side of the Green River. He also started a ferry operation on the river and was appointed postmaster of the first Brown's Park post office in 1878 (John Jarvie became postmaster, ferry operator, and also owner of the Parsons property following the doctor's death in 1881.) The Parsons cabin was used by the outlaw Matt Warner and the Chew family. For years it was known as the oldest building in Brown's Park. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was certainly over 100 years old when it was burned to the ground by some careless hunters during the summer of 1978. [56]

The late 1870s and early 1880s saw a substantial influx of new settlers arriving in Brown's Park, most of whom settled in the Utah section. Jimmie Reed and his Indian wife, Margaret, built a cabin on the south side of the Green River on what was then known as Jimmie Reed Creek. Billy Buck Tittsworth, Isom Dart's boyhood friend and rescuer, built on the river opposite Dr. Parsons. [57] Other settlers included Frank Orr, Hank Ford, Jim Warren, Dr. Warren Parsons (John's son), Griff and Jack Edwards, George, James, and Walter Scrivner, Tom Davenport, Tommy Dowdle, Frank Goodman (one of John Wesley Powell's men), Harry Hindle, and John Jarvie. [58]

|

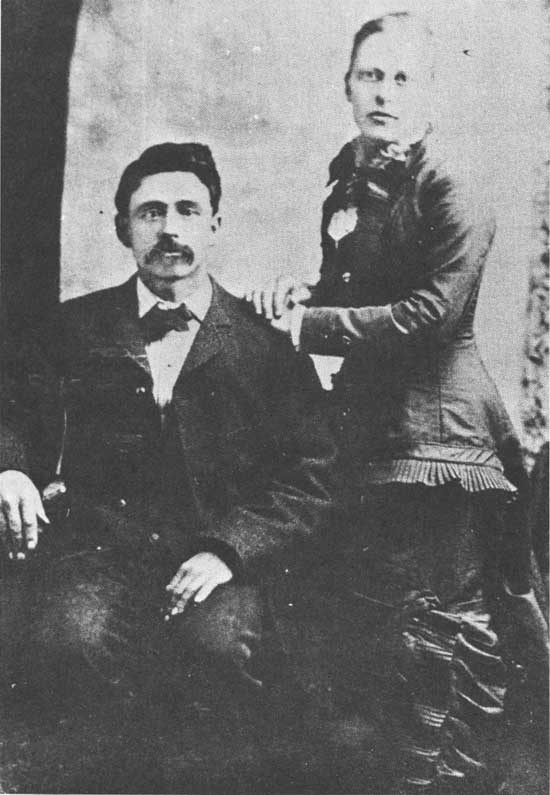

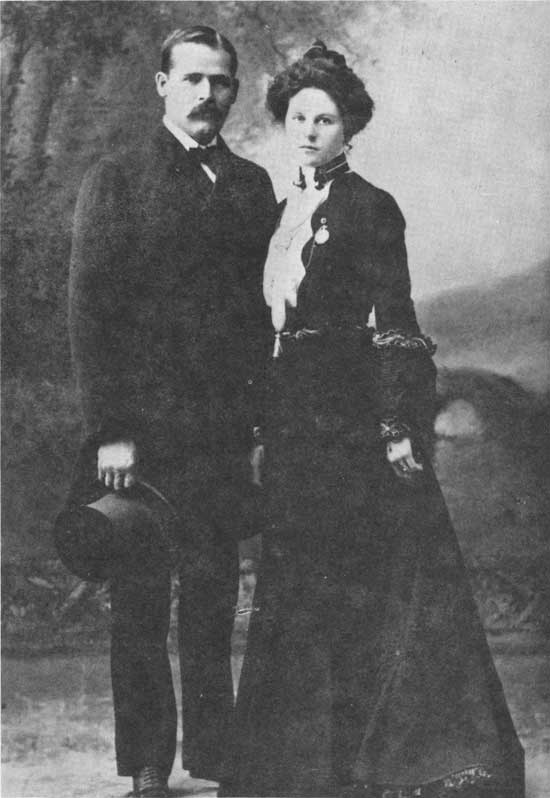

| Photo 9. Mr. and Mrs. Charlies Crouse. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

|

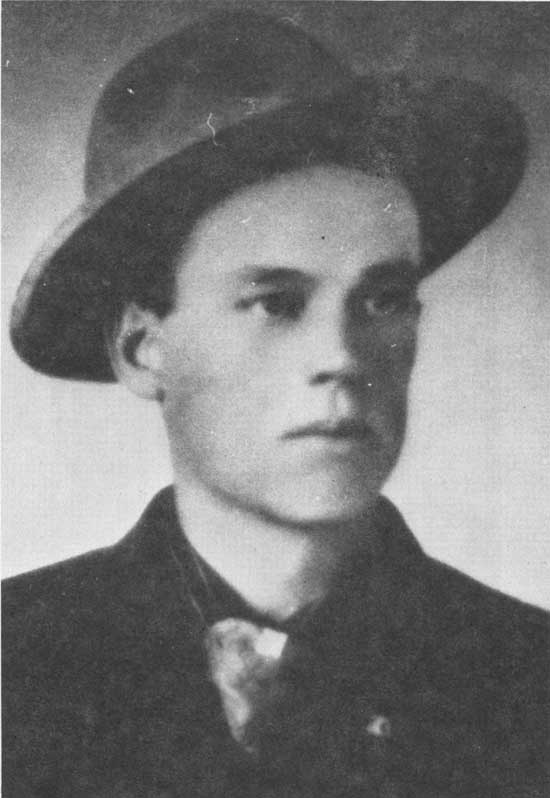

| Photo 10. Herbert Bassett. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

Charlie Crouse arrived in 1876 and along with Aaron Overholt set up a ranch near the head of Pot creek to breed and raise horses. Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1851, Charlie left home at the age of nine and wandered the West before settling first in Rock Springs and finally in Brown's Park. In 1879, he married Mary Law (the daughter of George Law, one of John Jarvie's early Rock Springs roommates) and in 1880, he bought out Jimmie Reed's claim and Jimmie Reed Creek became Crouse Creek. Crouse and Overholt opened a livery stable and saloon in Vernal, Utah, which gained a reputation as an outlaw hangout. [59]

Crouse became well known for his fine horses and often raced them. An article in the Uintah Papoose of Vernal, February 4, 1892, reads: "Charley Crouse and John Mantle are to have another horse race on the 14th of May. One horse against the other and 21 head of cattle on the side. . . .The winner is to get the two horses and 42 head of cattle. Forfeits are up and someone will certainly lose." [60] Charlie won the race but was accused of doping his opponent's horse. The issue raged for several weeks and a "Special Dope Issue" of the newspaper was devoted entirely to the subject on May 24. Crouse was eventually found innocent of the charges.

In the early 1900s, Crouse built a bridge and established the small town of Bridgeport a mile downstream from the Jarvie ferry and general store. Consequently, Jarvie's business suffered for two years until the bridge washed away and Bridgeport vanished.

Herbert Bassett, encouraged by his brother Sam who had come to Brown's Park years earlier with Kit Carson's son-in-law Louie Simmons, came to Brown's Park with his wife Mary Elizabeth and two small children, Josie and Sam, in 1877. In 1878, Ann was born, the first white child to be born in Brown's Park. Elizabeth could not nurse the baby so an Indian woman was found to serve as wet nurse. Consequently, Ann always claimed that she was part Indian. [61]

Herbert Bassett was a man out of place in the rugged Brown's Park frontier. He was intellectual and musical, a scholar in a place where hard labor, not mental ability, was necessary. Elizabeth, a gracious southern belle, decided "if she and her children were to survive, it was entirely up to her. She'd have to—figuratively and literally—rustle for their living. . .before long the Bassetts had a nice herd of Durham cattle. . . ." [62] Soon a group of Elizabeth's followers and admirers including Matt Rash, Isom Dart, Angus McDougal, and Jim McKnight became known as the Bassett Gang. "Technically, rustling cattle was a felony offense. It is not an exaggeration to say, however, that with very few exceptions, everybody. . .in Brown's Park engaged in it." [63]

Although the girls, Josie and Ann, were given proper educations (including Miss Porter's select Finishing School for Girls in Boston), they could ride and rope with the best cowhands and Ann, subsequently, earned the title "Queen of the Cattle Rustlers."

In the 1870s, a man named Clay, financed by Boston interests, set up the Middlesex Land and Cattle Company just north of Brown's Park. Having visions of a vast cattle empire, Clay threatened to "buy all the 'little fellows' out or drive them out of the country." [64] Only two outfits sold out to the Clay company.

Faced with this threat on their own cattle and land, the Brown's Park factions united, for once, to fight a common enemy. If there was nothing they could do to stop the Middlesex cattle from moving south, at least they could arrange it so that there would be nothing for the cattle to eat when they arrived. Thus the cattlemen of Brown's Park went into the sheep business. They fenced the gateway to Brown's Park with a barrier of sheep, and during the winter the Middlesex cattle starved for lack of food. [65] With the collapse of the cattle boom in 1884 and the hard winter of 1886-1887, Middlesex was finished. All that remains of the Middlesex empire today is the name Clay Basin north of the Park.

|

| Photo 11. Josie Bassett and Herbert Bassett at the Bassett Ranch. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

|

| Photo 12. The Bassett Ranch at Pablo Springs. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

Until the 1890s, the Brown's Park ethic allowed for horse thieves and cattle rustlers almost exclusively, "But with the arrival of Butch Cassidy. . . it was to enter upon a new era." [66] Ann Zwinger stated it nicely when she described Brown's Park as "a more or less permanent hideout for many who found total honesty a personal encumbrance." [67] Brown's Park became one of the three major hideouts along the Outlaw Trail (the others being Hole-in-the-Wall in Wyoming and Robbers' Roost in southern Utah).

Ann Bassett explained the situation to her friend Esther Campbell years later:

There was a reason why the people of Brown's Park were not interested in starting a row with the outlaws. In the first place, we did not know what their business really was. And we were pretty good at tending to our own affars. . . . They started no trouble with us and we let them alone. The young people of each group mingled and liked each other.

Ann hints at other interests, however, as she continues: "And let me say they had some cute boys with their outfit. It was a thrill to see Henry Rhudenbaugh [The Sundance Kid] tall, blond & handsome. ..." [68]

In Brown's Park, Butch Cassidy and his companions felt safe because

few law officers dared venture across the treacherous trails into the distant park, and those who did, whether from Colorado, Wyoming, or Utah, were faced with the frustration finding their quarry just out of reach across the state line. The outlaws who haunted the region knew their geography well in this unusual patchwork of state territories and easily managed to elude their pursuers. [69]

Pearl Baker writes that the Cassidy gang name is tied to Brown's Park:

. . .when they came to town to celebrate in Baggs, Vernal or other frontier towns. Saloon keepers called them 'that wild bunch from Brown's Park' and let them shoot up the place as much as they pleased, well knowing that they would come back and pay for all damage. It is said that bullet holes in the bar were worth $1 each, and the rest of the damage was always settled for generously. [70]

One of the outlaws' favorite hiding places was a cabin hidden among thick cedars not far from Charlie Crouse's ranch. There they would rest and play poker and if any lawmen approached, Crouse would send a rider to warn them. [71]

Butch divided his time between the hidden cabin and the Bassett ranch where he turned his attentions toward Josie Bassett. It was probably to Butch's advantage that Josie did not return his affections. "It would seem that Josie Bassett McKnight Ranney Williams Wells Morris had mighty poor luck at picking husbands and much better luck at getting rid of them." [72]

|

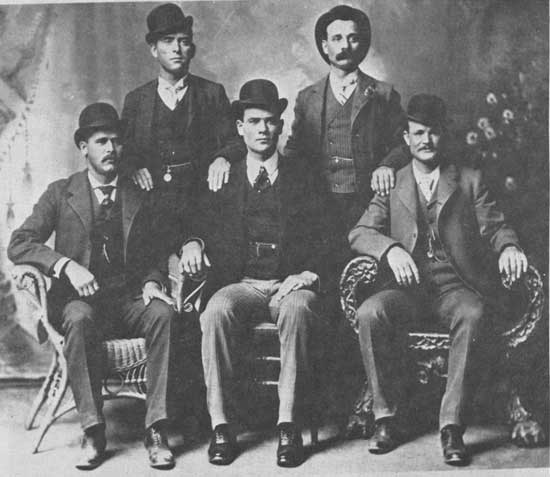

| Photo 13. Members of the Wild Bunch: Harry Longabaugh (Sundance Kid), Bill Carver, Ben Kilpatrick, Harvey Logan (Kid Curry), and Butch Cassidy. (Photo Credit: Utah State University Special Collections). |

Cassidy was held in high regard by the people of Brown's Park who were open to his friendliness and sense of humor. Lula Parker Betenson, Butch's sister, said "any of the local people would willingly harbor Bob [Butch] and other outlaws. Bob occupied a special place in their hearts. Wherever he worked, he did an honest day's labor for his pay. They trusted him." [73]

Matt Rash, a nephew of Davy Crockett, had come to the area as a trail boss for Middlesex. He fell in with the Bassett Gang and, along with Isom Dart, became one of Mrs. Bassett's strongest supporters and soon found himself engaged to Ann. He became the first president of the Brown's Park Cattle Association and helped to establish a dividing line separating the Brown's Park cattle from those of Ora Haley and the Two Bar cattle empire east of the Park. In spite of the line, Two Bar cattle continued to venture into Brown's Park and they continued to be absorbed by Brown's Park herds.

In April of 1900, a stranger arrived in Brown's Park giving his name as Tom Hicks and his occupation as a horse buyer. Ann Bassett, using female intuition, mistrusted Hicks from the start and soon came to the conclusion that he was not a cowboy. Shortly after his arrival, notices appeared on the cabin doors of the Park's more notorious cattle procurers advising them to leave the Park or else. The warnings were laughed at until one night Matt Rash received a visitor. "The ranchman did not even have time to stand up before three shots came in quick succession. After a few moments of silence. . .a fourth shot sounded. The party who had fired on Rash had paused long enough to kill his mare [which had been a gift from his friend Elizabeth Bassett]." [74] His body was discovered sometime later, in an advanced stage of decomposition, by young Felix Meyers.

|

| Photo 14. The Sundance Kid and his girlfriend, Etta Place. (Photo Credit: Utah State University Special Collections). |

|

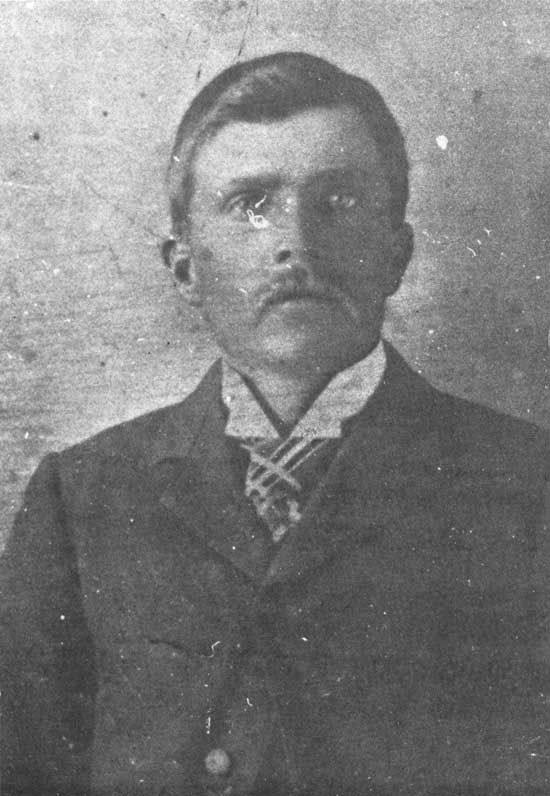

| Photo 15. Elza Lay, Butch Cassidy's right-hand man. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

Matt Rash was not the only one to die in such a fashion. Early one October morning, Isom Dart walked out of his cabin and two shots rang out. Isom fell dead, a bullet through his head. "Under a nearby tree, they found two empty thirty-thirty shells. . . . Everyone was now convinced—Ann Bassett had been right. Tom Hicks was the only man around who carried that caliber rifle." [75]

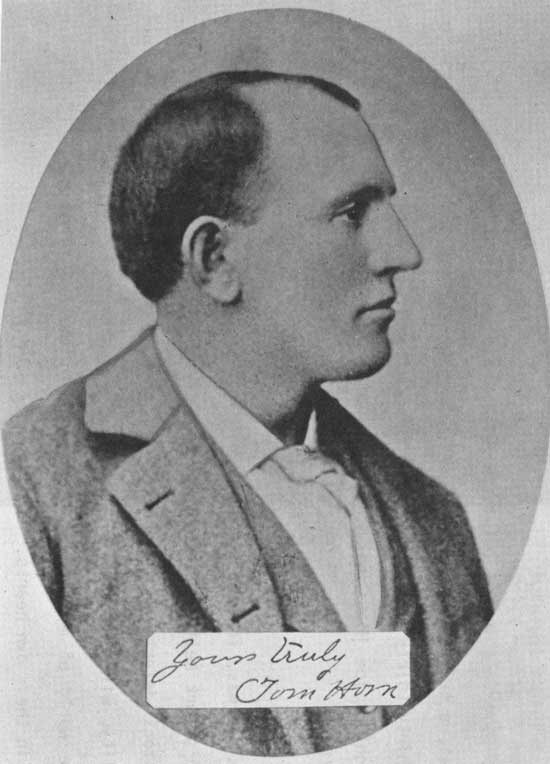

The stranger was, in reality, Tom Horn, infamous killer for hire. The people of Brown's Park believed that Ora Haley had been instrumental in hiring Horn as a "stock detective" to protect his cattle interests. "No one, in all probability, will ever know just who his employers were, for when Tom floated into the world of myth and legend, the men who had hired him locked their secrets in their own hearts." [76]

Ann Bassett, "Queen of the Cattle Rustlers," earned her sobriquet and declared a personal war on Ora Haley and the Two Bar empire due to what she considered was their insatiable lust for land of the small settler and out of revenge for the Tom Horn killings of her friend Isom Dart and her fiance Matt Rash. Her deeds included driving hundreds of Two Bar cattle over the cliffs into the Green River and have become Brown's Park legends. [77]

|

| Photo 16. Josie Bassett McKnight Ranney Williams Wells Morris at age eighty-five. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

|

| Photo 17. Josie at her cabin on Cub Creek near Jensen, Utah. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

She was eventually brought to trial in 1913 on charges of cattle rustling. The courtroom in Craig was packed with her supporters who saw the entire trial as a contest between the little people and the cattle barons. [78] They did not care if she was guilty or innocent. They simply wanted to see millionaire Ora Haley humbled and humbled he was. When he took the witness stand, he inadvertently admitted to having nearly twice as many cattle in Moffat County as he had filed with the county assessor. [79]

|

| Photo 18. Matt Rash, Ann Bassett's fiance and victim of Tom Horn. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

|

| Photo 19. Tom Horn, alias Tom Hicks, visited Brown's Park in 1900 as a stock detective. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

|

| Photo 20. "Queen Ann" Bassett in her seventies. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

In less than an hour, the jury acquitted the sweet, demure, little lady and the courtroom went wild. [80] A sign reading "HURRAH FOR VICTORY" was flashed on the screen at the Craig silent movie theater and the audience jumped to its feet cheering. Bonfires were lit in the main street and Queen Ann presided over an all night victory dance. [81]

Just as the demise of Fort Davy Crockett signaled the end of the mountain man era in Brown's Park, the flames from the bonfires in the streets of Craig marked the end of another era: the era of the cattle rustler and outlaw.

The bonfires marked the triumph of Morgan's "existences in quiet," for the commoner (if a female cattle rustler can be considered common) had defeated the empire builder and the people of Brown's Park could continue their day to day struggle with nature as victors. The people of Brown's Park had come for many reasons and when they arrived they were faced with the task of building a society that would be responsive to nature and geography. They discarded some institutions and modified others to fit their situation. Their outlook on law was not dictated by legislation, but rather, by common sense and necessity. Laws of nature became more important than the laws of men. Consequently, Brown's Park cattlemen did not terrorize local sheepmen, but became sheepmen themselves when sheepherding proved to be the more practical, economical response to the environment. And righteous young women saw no harm in smuggling homebaked pies to poker playing bandits hiding in the cedars on Diamond Mountain. Brown's Park society was a combination of the good, the bad, and the beautiful, and very often they were all one and the same.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

ut/7/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008