|

An Isolated Empire: A History of Northwest Colorado BLM Cultural Resource Series (Colorado: No. 12) |

|

Chapter V:

SETTLEMENT VERSUS THE UTE INDIANS

When the Ute nation was moved into the White River Valley, millions of acres of land were lost to white settlement. To most Americans during the nineteenth century, and especially to Coloradans, this loss of land was nearly sinful. To the mind of the 19th-century American, land was for one purpose: it was to be used to produce for profit. Whether by mineral exploitation, timber cutting or agriculture, each acre of land had to give a return, no matter how poor the quality of land involved. Most Americans had no conception of the marginal land that lay west of the Rockies; to them all acreage was fertile and could produce. This simply was not the case for the vast tracts of northwestern Colorado. Only the river valleys where water could be diverted were truly usable. Yet, the 19th century mind saw millions of acres of land going to waste, in the hands of indolent Indians who would rather hunt than farm.

To the average American, the Indian was a creature that was to be pitied. He was clearly a being that needed to be Christianized, as most religious leaders would so inform the public; he needed to be taught to read and write; but most of all he needed to be taught to become a self-sufficient farmer. The prevailing theory was that the Indian had to be made sedentary, taught skills, educated, and only then he could become a productive citizen. The public was told that the American Indian had to be civilized, meaning that he had to become a white man and adopt a value system entirely different from his own.

For the Indian, the task was nearly impossible. For hundreds of years most western American Indians have been nomadic - hunting in the summers, wintering in warm valleys. Now they were told to move into houses, live in one place year round, and farm the land. This concept was totally alien to the Indian. The Indian did not want to accept the demands of the white man. He was willing to make concessions such as wearing white man's clothes, eating his food, and even praying to his God, but to till the soil was asking too much. [1]

In this context, the Utes were forced to accept an Indian agency that was designed for their "conversion". The agents were religious men, ministers, who it was assumed knew what the Indian needed in terms of conversion. It was into this culture conflict that Nathan Meeker maneuvered himself. He was a typical 19th century American who believed in all the principles of Indian welfare and conversion. The Utes, at first, gracefully accepted and tolerated him, but he demanded too much too fast, and the cultural changes that were required by him proved overly demanding for the Ute people.

The first movements of whites across the mountains were small enough that the Utes did not worry about losing their hunting lands. But, by the late 1860's and the early 1870's, scattered settlers were coming into prime Ute lands. In addition, minerals had been discovered in the San Juan Mountains. Silver lodes were believed to be large and profitable. By 1870, many western settlers were demanding access to these rich lands. However, there was one major problem: the land in question belonged to the Ute Indians. The citizens of Denver, including leading businessmen, demanded that the natives be removed and that the San Juans be opened to settlement. Some of the more radical members of the community demanded extermination. [2]

In 1873, the Ute problem in southern Colorado was ameliorated when a treaty was negotiated by Felix Brunot in which the Utes gave up their claims to the San Juan Mountain region. In return, the Utes agreed to move to three agencies: one in New Mexico called Los Pinos, one along the White River in western Colorado, and one on the Uncompaghre River. The Brunot Treaty provided a temporary answer to a sticky problem and, thanks to the generous annuities, the promise of land, and an influential progressive chief, Ouray, the Utes were peacefully relocated. [3]

Luckily, the people of Colorado were able to deal with an intelligent and perceptive Ute chief who saw that resistance would do no good. Ouray, who spoke English and Spanish, and who was wise enough to realize that no one could stop the progress of the whites, used his power to persuade the Utes to accept their fate. In doing so, he prevented years of bloodshed that might otherwise have occurred.

While the Treaty of 1873 allowed white settlement in the San Juans many settlers who moved into Middle Park and North Park resented the use of the areas by the Utes for hunting. It was claimed that the Indians started forest fires, ran off livestock and wantonly killed animals. [4]

The Ute move into the White River Agency was peaceful and organized. Here the Utes could hunt, fish, and live as they always had. In addition, they were granted an annuity of some $10,000 which provided food, clothing, and other goods. The problem came when the agents tried to force the Utes to "learn white ways". [5] By the Brunot Treaty, the Utes had been granted all lands from the Continental Divide west into Utah and from the White River north to Wyoming. This meant that the Utes were given choice hunting grounds, in addition to excellent agricultural lands. However, the Ute saw no reason why they should not continue to use all the hunting lands in the old traditional manner. The United States government saw the question in a different light. Indian policy, under Carl Schurz, Secretary of the Interior, called for the "civilization" of the natives of America. This meant that the Indians should be taught English, that they should learn to read and write, that they should become agriculturally oriented, and that they should wear white men's clothing and live in houses. In short, they were to be transformed from nomads to a sedentary people, to become carbon-copy white men. That this policy was in force was in evidence no more strongly than at White River.

The White River Agency had a history of problems. Since its establishment in 1868, the agency had seen several agents come and go. Most left in total frustration. The next to last agent, the Reverend H. E. Danforth, quit because the government failed to deliver the promised annuities on schedule. The Indians deeply resented the fact that goods such as flour, blankets, and other supplies sat in the depot at Rawlins, Wyoming, and rotted. [6]

To succeed Danforth, Nathan Cook Meeker was chosen. In many ways, he was the worst possible choice, while in other respects he was perfect - a visionary altruist. Meeker was one of the founders of Greeley, Colorado (the Union Colony), and he was a minister, in addition to being a skilled agriculturalist. Meeker was sixty-seven years old and in deep financial trouble when he gained the appointment to the White River Agency. He was given the job, thanks to political pull on the part of the Secretary of the Interior, Carl Schurz. Meeker saw this position as an opportunity for testing out his theories on Indian re-civilization, while the job also would help pay off his debts in Greeley.

In 1878, Meeker moved to the White River Agency, which was then located just east of present-day Meeker. He quickly surveyed the region and decided to move the agency downriver to Powell Park, which he felt was perfect for agriculture. He planned to irrigate the valley from the White River, to build the Utes houses, to provide a school, to put up a commissary that would dole out the annuities, and to fence the land in the fashion of the white man. These concepts were totally new to the Ute, who while interested, failed to understand. [7]

Upon arriving at White River, Meeker met several Ute chiefs, including Douglas (so-called because he looked like Steven A. Douglas), Jack or Captain Jack, who had been raised by a Mormon family, the medicine man Johnson, and the fat Colorow. Douglas seems to have been the main spokesman for the Utes, and when Meeker explained his great plans, Douglas said that the Utes were not interested. When Meeker finally said that these plans were orders from Washington, D. C. the Utes, awed by "Washington" agreed to try the new system. [8]

With Douglas' and the other Utes' reluctant approval, Meeker began his great experiment. The agent began by moving the agency to Powell Park, where he erected several buildings, including a house for himself, a school, and a store. His daughter, Josephine, was on the government payroll as schoolmistress and doctor. His wife, Arvella, became the self-appointed religious teacher of the Indians. [9] Meeker found that his main problem was keeping the Utes on the reservation. They were constantly moving out to go hunting. To hunt they naturally needed guns and ammunition, for which they traded goods with merchants at Hayden and Lay, Colorado. Meeker found that this "impeded progress" and decided to keep the Indians on the reservation by using their rations as bait.

Meeker imported agency employees from Greeley, where he knew he could find "sober, upright men" to work with the Indians. He employed a Mr. Curtis from the Los Pinos Agency to supervise the work of ditch digging, which began under his and Captain Jack's auspices. Over 5,000 feet of irrigation ditches were dug; the Indians were paid; and everyone settled in peaceably for the winter of 1878. [10] Through the summer of 1879, Meeker worked with the Utes trying to get them interested in growing crops that could pay for the agency. Meeker found that the Indians became more and more disinterested; soon most of them left for the mountains to hunt. Meeker's letters progressed from optimistic in March, 1878, when he first arrived, to more and more gloomy. By September, 1879, his communications showed fear, not just gloom. [11]

During the summer of 1879, the Meeker plan seemed to go fairly well. However, there were several incidents that increased tensions. First, a series of forest fires swept the Parks and much of the Yampa Valley; it was an extremely dry summer and such fires were natural. However, many white settlers in the Parks, especially Egeria Park, blamed the Utes, claiming that they were trying to get rid of settlers by burning them out. Such an uproar was caused by the fires that numerous complaints poured into Denver, and the governor's office asked for troops. Indeed, some forty cavalry were sent to Middle Park from the 9th Cavalry Regiment. These were the "Buffalo Soldiers," an all-black regiment, much feared and hated by the Utes. [12] The other incident that summer was the reported burning of a home near Hayden in August, 1879. A "posse" from Hot Sulphur Springs was sent out to find the two Indians held responsible for the "outrage", "Bennett" and "Chinaman". They were found. Meeker, having been apprised of the situation, refused to go to Hayden to look at the home. Douglas said it had not been touched, which was true. Meeker said that if a white man had said that it had been burned, then Douglas was lying. [13]

As the summer progressed, Meeker was eager to get as much land as possible under cultivation. He decided that the racetrack the Indians had at the agency had to go, because the land should be put to use; racing was wasting the time of the natives; there were too many horses for the park, and there was continual gambling during the races. When Meeker suggested that the Indians should kill some of the animals to lessen the grazing burden on Powell Park, the Utes were outraged. [14]

On September 10, 1879, the tensions that had been growing came to a head. Chief Johnson went to Meeker's home to discuss the destruction of the horsetrack. Meeker refused to listen to Johnson's protestations and the chief, in anger, shoved Meeker against a hitching post. The old man fell and bruised himself. With this "assault" Meeker wired Rawlins, Wyoming, with the message that he had been seriously injured by Johnson, and that a plowman had been shot at on September 8th. [15] He then requested help from Governor Frederick Pitkin or General John Pope. Neither the War Department nor the Bureau of Indian Affairs felt it necessary to send in troops at that point.

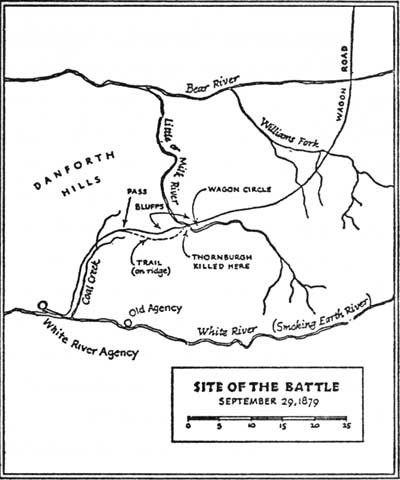

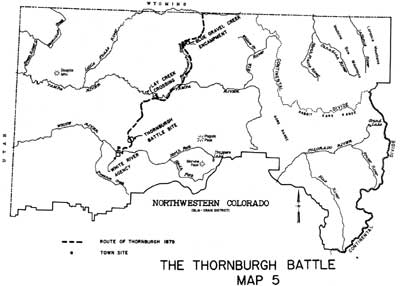

Finally, after much communication between Nathan Meeker, Fort Steel, Wyoming, General John Pope, and the War Department, it was decided to send troops to White River to arrest the troublemakers, and to restore order at the agency. In late September, Major Thomas T. Thornburgh was ordered to march to White River with a detachment of 190 men. He had with him two companies of cavalry under the commands of Captain J. S. Payne and Lieutenant B. D. Price, and a long supply train. [16] They camped along Fortification Creek at the mouth of Blue Gravel Creek, and then marched to the Yampa River where depot was established south of Lay, Colorado. Thornburgh, totally unaware of conditions at White River, was forced to rely on his scouts, including Joe Rankin, an avid Indian-hater.

On the second day out, the Thornburgh detachment camped along the Bear (Yampa) River, and then moved into Coal Creek Canyon not far from White River. Here they were met by Douglas and Colorow, along with Captain Jack. Major Thornburgh and the Indians talked about what the soldiers were doing in the area, and Thornburgh explained he had been ordered there by Washington. Rankin did his best to discredit the Ute's claims that they came in peace and would leave the soldiers alone if the troops did not come to White River. Thornburgh, much to his credit, ignored Rankin. Thornburgh promised that he would reconsider moving to White River and that he would tell Douglas what he decided before he moved.

Meeker, in the meantime, sent a message to Thornburgh. He asked that five men be sent to the agency to look over the situation, and that Thornburgh camp nearby. [17] Thornburgh replied that he would camp along the Milk River, and then send five men with E. H. Eskridge (an agency employee) to White River. [18] Meeker wrote to Thornburgh on September 29th that he expected the five men the next day, and that Douglas would fly the American Flag as a sign of peace; this letter never reached Thornburgh.

In order to reach White River on September 30, Thornburgh had to traverse a small canyon into the valley. Here, as Rankin pointed out, would be a perfect place for an ambush. This was where the Utes under Douglas were placed along the canyon rims, waiting to see what would happen. At this point, Douglas and Colorow lost control of the young warriors. Douglas and Thornburgh both expected to talk, but someone fired, and before Douglas could stop the firing, the Utes and the Army were engaged in a battle.

Thornburgh was killed almost immediately. The soldiers fled back toward the hills to the northwest. The wagons were circled, and fallen horses became breastwork. The firing continued all day, and when the day was over, fifty men had been killed or wounded, including nearly all the officers. [19]

Joe Rankin made a twenty-eight hour dash to Rawlins to report the battle. On October 1, 1879, the garrison at Fort Russell heard that the Utes had nearly wiped out the detachment at Milk River. The War Department ordered Colonel Wesley Merritt to move from Fort D. A. Russell (near Cheyenne) via the Union Pacific to Fort Steele. Merritt was ordered to take two hundred cavalry and 150 infantry to relieve Captain Payne at Milk River. [20] The confusion was compounded by the Denver newspapers which reported an uprising on the Southern Ute Reservation.

Captain F. S. Dodge, who was stationed in Middle Park with his Ninth Cavalry, the much-feared black troops, was ordered on October 1st to relieve Thornburgh. He arrived on October 2nd and reinforced the besieged troops. Meanwhile, Merritt, moving south, arrived on October 5th, only to discover that the fight was over. [21] The Utes withdrew in the face of his command.

|

| Site of the Thornburgh Battle, September 29, 1879. From Robert Emmitt, The Last War Trail, page 201. |

While the Thornburgh detachment was under attack, the White River Agency was also attacked by the Utes. On the night of September 30, 1879, the Indians at the agency rose up and killed all eleven white males at White River. Meeker was killed and his body pierced by a barrel stave. The Utes then took hostage Mrs. Meeker, her daughter, Josephine, Mrs. Shadrack Price, and her two children. [22]

It was not until October 13, 1879, that the newspapers got their first dispatches describing the agency massacre as portrayed by Merritt, second on the scene. The headline blazed, "A SCENE OF SLAUGHTER", and the citizens of Denver demanded immediate action. Governor Pitkin denounced the massacre in no uncertain terms, and also pointed out that 12,000,000 acres of land could be opened with the removal of the Utes. [23] Herein lay the perfect opportunity to remove the Indians for good.

The Ute uprising came to an end when Chief Ouray was able to send a message to the Northern Utes to lay down their arms. Douglas, Colorow, Johnson, and others fled into the hills where they awaited the outcome of negotiations with Ouray. Former Indian Agent, General Charles Adams, working with Ouray, managed to secure the release of the captives. None of the hostages were harmed, and Josephine actually praised the humane treatment they had received. [24]

The Utes had been initially provoked, but despite their fair treatment of the captives, and regardless of Douglas' attempts at peace, the citizens of Colorado were demanding "the Utes Must Go". The outcome of the Meeker Massacre was that a commission was established to find out what had happened, and to punish those who were guilty of the uprising. The commission had only the white women as eye-witnesses, and Ouray refused to let them testify (under Ute law their testimony was null and void). Ouray demanded a trial in Washington, D. C., where he felt the Indians would get a fair hearing. Since the commission did not have such authority, Douglas and several minor chiefs were put on a train for Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, on the pretext that they were going to Washington. They were held in jail at Leavenworth for several years; this was the extent of the punishment for the Utes who took part in the uprising. [25]

More importantly, the rebellion provided the reason for the final removal of the Utes. In 1880, a delegation of Utes left for Washington, headed by Ouray. A treaty was put together by which the Utes lost their western Colorado lands. The Indians were given two reservations. The Southern Utes were put on the La Plata Reservation, while the Northern Utes were moved to Utah to the Uintah Reservation. In addition, they were given $60,000 in back annuities, and $50,000 in new annuities. Three-fourths of the males of the Ute Tribe had to sign the treaty before it became effective. [26]

On August 20, 1880, Ouray died, and the Utes lost one of their best spokesmen. However, despite his influence among the whites, it is doubtful that he could have saved the Utes from being removed. In that same year, General R. S. Mackenzie with six companies of cavalry and nine companies of infantry from Fort Garland, began moving the Ute nation out of northern Colorado. There were only about 1,500 people total, and on September 7, 1881, the last of the Utes passed the Colorado and Gunnison River junction into Utah. The next year, 1882, Congress declared the vacated Ute lands open for filing, and what had been hunting grounds were available for agriculture and ranching. [27]

The causes for the Meeker Massacre were many and complex, but the basic problem was the total lack of understanding between two cultures. A series of preventable events transpired to create the atmosphere for trouble. The worst offenders in the Ute removal were the people of Colorado, who found the perfect excuse to get rid of the Utes and to take their land. Because of the uprising of 1879, the balance of northern Colorado was cleared of Indians, and the northwest corner was open to all comers. As Senator Nathaniel Hill of Colorado so ably stated, the injustice done to the Ute was inexcusable, but the year 1879 signaled a new era in western Colorado.

|

| Map 5. The Thornburgh Battle (click on map for an enlargement in a new window) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

co/2/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 31-Oct-2008