|

The Valley of Opportunity: A History of West-Central Colorado BLM Cultural Resource Series (Colorado: No. 12) |

|

Chapter V:

THE TRANSPORTATION FRONTIER IN WEST-CENTRAL COLORADO

"Like Aladdin's magical carpet, the railroad crossed wide rivers, spanned barren deserts, climbed towering mountains, almost in a breath."

—Unknown

Adequate transportation, water, road, or rail, caused growth in nineteenth century America more than any other single factor. West-central Coloradans realized this, and over the years, worked hard to build and also encouraged the development of systems to move goods and people. Often construction capital came from outside the area, however by 1900, most roads in west-central Colorado led into Grand Junction. The river and stream valleys provided relatively easy paths and for that reason, builders prized those routes. The Continental Divide's rugged passes formed the greatest barrier for these transportation pioneers.

Road building dated to 1830-1831, in west-central Colorado when James Yount and his associates laid out what was called the Old Spanish Trail. One routing of the trail, known as the Northern Branch, followed the Gunnison River north to the Grand River and then west along that waterway into Utah. The trail was lightly used until the 1850s, during the Mormon Migration to Utah. The "Saints" sought new routes into Zion for future settlers and to connect their southwestern settlements with Salt Lake City. Mormons scouted the Grand River Valley and felt it could be used. Immigrants favored the Platte River-Wyoming route and the trail through western Colorado never saw heavy use. [1]

Large numbers of travellers did not use the Gunnison River trail until the 1880s, with the opening of the Ute Reservation for settlement. Many people followed the "Old Ute Trail" via Cochetopa Pass and the Gunnison River because that was the route used by Native Americans as a trade passageway to New Mexico. [2] Fremont and other explorers used that trail and popularized it; by 1880, it was well known, as were the dangers it presented.

Grand Junction's earliest settlers followed this pathway and successively overcame many inherent problems. Travelling in a Conestoga wagon with a team of two, four, or six oxen these families hauled all their worldly possessions hundreds of miles over roads full of tree stumps, rocks, steep grades and they used fords or ferry boats to cross rivers. Leaving their homes in late spring these future Coloradans traveled an entire summer to reach their new farms. Broken wheels, axles, and other problems plagued the travellers. Often family heirlooms, such as furniture, were discarded on the route to assure safe conquest of the mountains. Potable water was in short supply.

Highwaymen posed a constant threat. So too did the death of a oxen. Wagon trains were not widely used in this type of migration, but often two or three families would meet on the trail and travel together. Despite all the hardships, intrepid souls did reach Grand Junction ready to build their fortunes in the valley of the Grand River. [3]

The Grand River itself was a favored route for transportation planners since the 1860s. In 1867 a group of Denver business leaders felt a wagon route between the "Queen City" and California could stimulate trade and help assure Denver a position as the commercial leader of Colorado. These Denverites hired surveyors, and that year they laid out the Colorado and California Wagon Road which crossed the Continental Divide near the head of Clear Creek and proceeded west until it bisected the Grand River, it then followed that watercourse west through the Grand Valley and DeBeque and Ruby Canyons into Utah. The backers ran into financial difficulties and the project never got beyond the planning stages. [4] However, it did help draw further attention to the Grand River as a practical route for east-west communications.

The 1870s witnessed the first actual road building in the region. After the Brunot Treaty of 1873, and with the establishment of Ute Agencies on the White and Los Pinos Rivers, federal authorities recognized a need for roads to connect these far flung outposts. One such line was built by the U. S. Army via Rifle Creek and it became known as the "Government Road." While never heavily used by troops, it did provide access into the area once other Anglo-Americans arrived and it encouraged settlement around Rifle. Local legend maintained that Rifle Creek got its name because one of the soldiers who surveyed the road left his gun along the stream and it was found by ranchers in the 1880s, thereby giving them something to call the creek. [5]

The silver discoveries at Red Cliff and Aspen during the late 1870s, led to frenzied road building activity. Aspen, in particular, felt the impact of highway construction. The original conveyance between Red Cliff and Leadville was the mule train. [6] These "Rocky Mountain Canaries" were used also between Aspen and Leadville (or Buena Vista) during the camp's earlier years. [7] A lack of adequate transportation led to high prices for supplies such as flour and liquor. In addition, it was financially profitable for only the best grades of ore to be shipped out for refining. The trip itself was costly and arduous especially in the spring or fall travel season. [8]

Such problems were partially solved by building toll roads over mountain passes. From the early days, Red Cliff and Aspen promoters called for highways to aid in economic growth. As early as 1866, Denver planners envisioned crossing the Continental Divide and using the Eagle Valley as a route west that would eventually reach into old Mexico. [9]

However, it was not until the late 1870s and the silver discoveries, that roads penetrated the Valley. Kelly's Toll Road was opened in 1879, from Leadville via Tennessee Pass to Eagle City and Red Cliff. That year two companies, Wheaton and Wall & Whitter, started stage service from Leadville to Red Cliff. Henry Farnum then introduced daily stage service between those two points. [10]

Aspen's development as a transportation center followed Red Cliff's and was closely tied to development of the silver industry. The first route into town crossed Taylor Pass and connected Buena Vista on the Denver, South Park, and Pacific Railroad. H. P. Gillespie was the driving force behind this project which was finished in 1880. [11] Stevens and Company operated the original stage service along that road. [12] Taylor Pass was not the shortest way to Leadville and other Aspen promoters soon turned their attention to Independence Pass, a rough but shorter route.

B. Clark Wheeler, during 1880, started surveying Independence Pass as a possible wagon road and the next January he, along with H. P. Cowenhoven and Andrew MacFarlane, incorporated the Aspen, Hunter Creek, and Leadville Toll Road Company to build and operate a tollway. [13] The route was opened the next year and business boomed. The road aided Aspen's prosperity by shortening the haul and thereby decreasing freight rates. [14] However, descriptions by travellers between Aspen and Leadville were quick to point out hazards along the pathway and weather conditions, especially winter snows, made the road impassable much of the year. [15]

Further to the west, roadbuilding took place in 1881, when the first settlers arrived. During that year and into 1882, a toll road was constructed from Gunnison to Grand Junction. This first thoroughfare was described as an impediment to commerce and totally inadequate for local needs. [16] Early stage service was a buckboard wagon run by H. R. Hammond. [17] William Hunter operated a freight line between Montrose and the Grand River over this road at the same time. [18] Seeking other routes to Grand Junction, toll operators such as W. P. Poff undertook construction of pathways, such as the Unaweep Road, from Ouray and Telluride or other San Juan locations. [19]

The largest single road building effort of the 1880s was the Roan Creek Toll Road that was to follow the Grand River from Grand Junction to Glenwood Springs, thereby giving Grand Junction traders a more direct and easy access to Aspen and Red Cliff. DeBeque Canyon blocked such a route and had to be breached. In the past, the canyon's old trails from Parachute (Grand Valley) to Grand Junction had taken two weeks and considerable extra distance to traverse. [20] In 1885, Edwin Price, H. R. Rhone, D. P. Kingsley, and W. A. E. Debeque formed the Grand River Toll Road Company, also known as the Roan Creek Toll Road. [21] The idea for this project began in 1884, when the Grand Junction Board of Trade called for an extensive program of road building, particularly along the Grand River. [22] This boosterism continued into the next year when Rhone and his associates made public their plans. [23]

The Roan Creek Road itself took about a year to build. Cost estimates varied from $12,000 to $18,000. [24] Wagons used the road for $2.50, while the George Barton and Johnny Hynes' stage line offered passenger service on a two day schedule between the termini with an overnight stop at Parachute, Colorado. [25] The road remained in operation from 1885 to 1889, when the Denver and Rio Grande purchased it for roadbed for its proposed standard gauge railroad line to Grand Junction. [26] Success of the Roan Creek Toll Company encouraged others to build roads throughout west-central Colorado during late 1880s and 1890s.

The Roaring Fork Valley experienced the first road building craze in west-central Colorado during the early 1880s. However, the first major road, between Aspen and Glenwood Springs, was laid out by B. Clark Wheeler in 1882. [27] Charles H. Harris soon became the man responsible for the Roaring Fork's trails. He projected and built many tollways in the Valley during the decade. [28] Barlow and Sanderson offered stagecoach service to various points in the region, with competition between Aspen and Glenwood from the Kit Carson Stageline and the Western Stage and Express Company. That trip took twelve hours one way. [29] Many of these roads were crude at best and travel remained uncertain. [30] However, as time progressed the region's road system was improved and expanded. In 1883, Pitkin County built a trail from Aspen to Emma, [31] and two years later, Jerome B. Wheeler constructed a tollway from Carbondale to Aspen in order to haul coal. [32] The last major pathway to be opened in the Roaring Fork Valley was completed in 1891, along the Crystal River between Carbondale and Marble so as to serve as a feeder for the railroad at the former location. [33]

Equally important in allowing Aspen to maintain contact with the outside world was the telegraph. Much of western Colorado received telegraph service only in conjunction with the railroads but Aspenites were impatient for "talking wires" and in 1883, Gillespie convinced Western Union to build a line from Granite to Aspen making it among the first west-central Colorado cities to have such communications. [34]

Red Cliff, the area's other mining district, was as anxious as Aspen to be the center of a road system. Arrival of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad in 1882 allowed Red Cliff to become the headquarters of large wagon freighting operations. Roads were built to Glenwood Springs and on to Rifle as well as to Gilman. [35] In 1880, plans were put forth to build across Vail Pass but such a route was not completed for 60 years. [36]

West of Glenwood Springs progress was somewhat slower because fewer settlers filled the area. Stage lines were built to connect various towns within and from outside the region such as from New Castle to Meeker or the Government Road from Rifle to Meeker. Not until 1887 did the citizens of Garfield County pressure the local government into building road. The county allowed its residents to pay their taxes by road crew work. Even so, much of the area's transportation was via trails well into the twentieth century. [37]

Stock trails offered pathways that travellers used in west-central Colorado. The first established was the JQS in 1885. This was the first of six stock trails that led from the Grand Valley to the top of the Cliffs by 1920. Stock trails offered pathways that travellers used in west-central Colorado. The JQS trail ran from near Rifle to the top of the Roan Cliffs. H. W. Hallett and William (Billy) Chadwick proposed and built the JQS in 1885. [38] This was the first of six stock trails that led from the Grand Valley to the top of the cliffs by 1920, however, there were no wagon roads. [39]

In the vicinity of Grand Junction, road building during this period directed itself to connecting outlying settlements with the Grand River and the Denver and Rio Grande Railway. In 1884, the Hogback Road was mapped and built from Grand Junction into the Plateau Valley. [40] At approximately the same time, Gordon's Toll Road from the Grand River to Glade Park opened for business, [41] as did a similar road to Little Park. [42] Other roads into the Glade Park area were little more than stock trails and often were used by stockmen to drive cattle from summer to winter range in the Grand Valley. [43] The first road to Grand Mesa was built in 1891 from DeBeque up the northwestern rim of the mountain. [44]

These and other roads throughout west-central Colorado saw continued use because many settlers preferred to use wagons, not railroads, to reach their new homes. This trend continued into the twentieth century. [45]

Further settlement provided state Senator Edward T. Taylor with the argument he needed to convince Colorado's legislature the next year. The law provided for an allocation of $40,000. [46] The senator received support for this idea for two reasons. Promotion of settlement attracted many backers but moreover the idea of uniting the eastern and western slopes with a road especially appealed to merchants in Denver who saw possibilities for increased trade. [47]

Construction of the turnpike started in 1899, and was finished four years later. The roadway eventually became the basis of modern U.S. Highway 6. Over the years the road has been Colorado's main east-west trade and developmental axis. [48]

At the same time that Taylor's State Road was being built, the Good Roads Movement swept the nation. In many ways Taylor's highway was part of this phenomenon. [49] Much of the clamor to upgrade the nation's roads came as part of the automobile craze that touched west-central Colorado in the early years of the twentieth century.

The first motorcar visited Glenwood Springs in 1902, driven by Colorado Springs stockbroker W. W. Price. A year later Grand Junction had the same experience as "Old Pacific," a two cylinder Packard, passed through town on an overland trip from San Francisco to Denver. [50] The auto's popularity led to new pleas with Colorado's state legislature for money to build roads and from 1906 to 1920, towns throughout the region hotly competed for highways. [51]

By 1910, the Federal government also became interested in these projects by announcing plans for a transcontinental highway. The cities of west-central Colorado, especially Fruita, Grand Junction, and Glenwood Springs, campaigned for inclusion on the path. Drives were sponsored, endorsements gathered, and arguments marshalled as to why west-central Colorado had the best route available. Foremost, the Taylor State Road could be used thereby cutting construction expenses. The boosters prevailed and by 1916, when the first paved transcontinental highway was laid out, it bisected west-central Colorado. [52]

During these same years, the road system around Grand Junction grew, thanks mainly to the efforts of John Otto. In addition to being the father of Colorado National Monument, he built many roads in the area. Among these were the Land's End Road, on the side of Grand Mesa, [as] well as trails on that Mesa and the Serpent's Tail from Fruita to Glade Park. These paths furnished easier access for two remote and inaccessible areas thereby encouraging grazing and recreation. [53]

Access was just one problem early transportation faced. Another possibly greater one was the Grand River. While it provided water for irrigation, it served as a barrier to through routes. People wishing to cross the river had to depend on finding shallow fords to wade or drive their wagons through or they used ferries. The second alternative was more practical, and towns along the waterway relied on those for many years. [54]

Occassionally, enterprising individuals built toll bridges, but most towns sought state aid to bridge the Grand River. In 1886, a state bridge was built at Grand Junction and from then until the early twentieth century, Colorado financed many such projects up and down the river. While spring floods constantly threatened these structures they proved much more satisfactory than the earlier ferries. [55]

Wolcott, Colorado, offered a good example of the economic impact of a river ford to bridge site as well as the interdependence of road travel and railroad transportation. When the Denver and Rio Grande Railway reached the area in the early 1880s and created Russell's Siding, a new route was opened north to Steamboat Springs because the Eagle River could be more safely forded. A small settlement grew up at the ford and became known as Wolcott. By 1890, a road between Wolcott and McCoy was built and state funds were secured to build a bridge over the Grand River at "State Bridge" near McCoy.

|

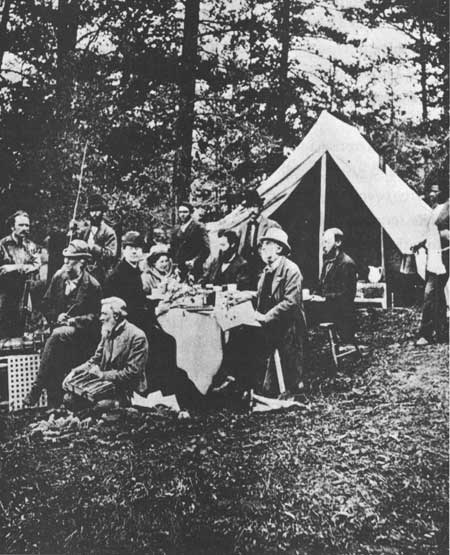

| Roads were important as seen in this view of the Grand River Canyon where the Rio Grande railroad takes up one side and a wagon road from Glenwood Springs uses the other side. Photo by Colorado Historical Society |

|

| Surveyors were important to establish roads, boundaries, and to describe the "New West". Photo by Colorado Division of State Archives |

Construction and opening of the bridge led to more intense use of the Wolcott-Steamboat Springs route. It became the gateway to northwestern Colorado until 1908, when the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific Railway reached Steamboat Springs. Wolcott served as a terminal point where teams changed, wagons loaded and unloaded, and passengers stayed over at the local hotel. The 85-mile trip took 12 hours by stage coach or 4 days by freight wagon. There was no stage station per se at Wolcott; rather a livery stable and roominghouse served traveller's needs. [56] This type of multi-mode transportation system became prevalent throughout west-central Colorado in the late nineteenth century as railroads reached the region.

Iron horse fever touched the western reaches of the territory well before initial settlement occurred. In 1862, Congress passed the first in a series of Pacific Railroad Acts to subsidize construction of a line from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to California with the route to be determined later. This opening gave Colorado promoters, most notably Governor John Evans, the opportunity to try and attract the railroad to Colorado. Boosters hired surveyors to seek a route west from Denver. Reports indicated that the Grand Valley offered a possible solution, however, crossing of the Continental Divide presented an insurmountable problem. In 1866, the Union Pacific line was finalized through Wyoming, much to the disappointment of Evans and his associates. [57]

The railroad situation in west-central Colorado remained static for the next 15 years. Developments on the eastern slope took place that would impact transportation throughout the state and region. In 1870, William Jackson Palmer, a Union Civil War General, arrived in the territory as an engineer for the Kansas Pacific Railroad and immediately was taken by the wealth of railroading possibilities that Colorado offered. In that year he chartered the Denver and Rio Grande Railway with plans to run from Denver to Mexico City along the front range. To save money he decided to use a gauge of three feet rather than the standard four feet eight and one-half inches because the "narrow gauge" was cheaper to build and more adaptable to mountainous construction than was standard gauge. [58]

Competitive pressures and the Santa Fe Railroad's capture of Raton Pass blocked Palmer's way to the south but he was determined to build west, tap the mountain trade, and possibly build on to Salt Lake City. Throughout the seventies, Palmer fought to keep the road solvent while expanding his railroad. Toward the decade's end, many financial problems were settled and the Denver and Rio Grande was ready to set forth on a new, and more extensive program. [59]

Part of the plan called for construction of a line west from the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River to Salida and then on westward via Marshall Pass to Gunnison, Colorado. From that town the road would follow the Gunnison River to the future site of Grand Junction and thence west along the Grand River into Utah. [60] While Palmer's crews were busy laying lines, other rail promoters also cast an envious eye on the Grand Valley. John Evans, denied the Union Pacific in Colorado set out during the late seventies to build his own transcontinental line, the Denver, South Park and Pacific (DSP&P). DSP&P surveyors paralleled Denver and Rio Grande crews through the Grand Valley during 1880 and 1881, but financial problems kept the company from ever building such a railway. [61] Another company, the Greeley, Salt Lake and Pacific, a Union Pacific subsidiary, also surveyed routes along the Grand River at the same time. Again the reports came to naught, [62] and it was Palmer's Denver and Rio Grande that eventually penetrated the region with its twin ribbons of steel.

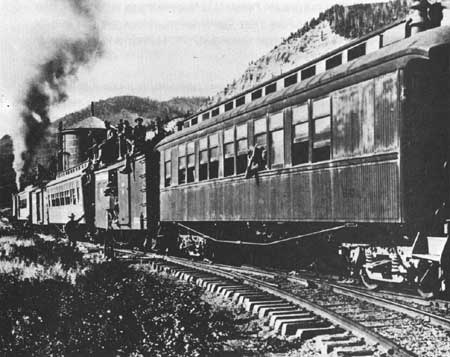

In 1881, the first link in Palmer's plan was completed, when the narrow gauge was built into Gunnison by way of Marshall Pass. Over the winter, supplies and men gathered at the end of track preparing for the 1882 season and the push to Grand Junction. The line, known as the Utah Extension, followed the 1853 Gunnison route almost exactly. [63] During the height of the 1882 season, more than 1,000 men worked on Denver and Rio Grande construction crews, facing all variety of dangers and hardships. [64] By September of that year, Kannah Creek was reached. [65] On November 21, 1882, the first train chugged proudly into Grand Junction amid wild cheers, great speeches, fireworks, and a generally riotous atmosphere. [66]

While construction progressed so did corporate events. On July 21, 1881, Denver and Rio Grande management incorporated the Denver and Rio Grande Western, commonly referred to as the Rio Grande Western or just the Western, under the laws of Utah territory. The new company was to build and operate a railroad from Salt Lake City to the Colorado state line west of Grand Junction and there connect with the Denver and Rio Grande. Before rails reached Grand Junction, the Denver and Rio Grande leased the Denver and Rio Grande Western so as to finish construction and commence operations. [67]

Wasting little time on celebrations, Denver and Rio Grande management turned its attention to Utah after arrival at the confluence of the Gunnison and Grand Rivers. On December 19, 1882, rails reached the state line, [68] while crews continued to build west. By the end of March 1883, track laying was completed and Grand Junction, a community in its infancy, enjoyed what many towns sought and never achieved: a transcontinental railroad. [69]

Grand Junction benefited from these rail connections, but the town also advanced because Denver and Rio Grande management chose it as the location for major shops and engine servicing facilities. The company built a roundhouse, repair shop, and other services at Grand Junction. In 1883, the western terminus of the Denver and Rio Grande was specified as Grand Junction as was the eastern terminus of the Rio Grande Western. While the history of Grand Junction is much more than just the railroad, there can be no doubt that it contributed to the city's prosperity. [70] However, if the iron horse brought new wealth it also brought problems. When the railroad reached town the crews went wild drinking, celebrating, and carousing. Grand Junction experienced many of the same problems of lawless behavior normally associated with a Kansas cow town or the "Hell on Wheels" tent towns that followed Union Pacific construction crews across Nebraska and Wyoming. Grand Junction town fathers were upset but little could be done to stop the revelry. [71] Eventually the problem cured itself as the end of track moved westward into Utah. [72]

1881 and 1881 proved to be two big years for construction on the Denver and Rio Grande while towns nearby on the western side of the Continental Divide also received rail service in those years. The Rio Grande decided earlier to build north along the Upper Arkansas River from Salida to Leadville to capture the mine trade. The "Cloud City" market proved lucrative [73] and after the Eagle Valley discoveries, a narrow gauge line was built over Tennessee Pass and into the Valley. Rails reached Red Cliff in 1881, and then Eagle the next year. [74] There the railroad stopped for nearly five years.

The great amount of construction during the early 1880s sapped Palmer's railroad as well as his own wealth and he lost control of the Denver and Rio Grande, which went into receivership. The General did retain ownership of the Rio Grande Western. To survive, both companies needed each other's good will. However, both sides were hostile to each other. In 1884, relations deteriorated to the point of open warfare that centered itself in Grand Junction because of the termini. Neither company would interchange traffic with the other and the yards soon filled with freight cars. The town found itself cut off from the outside world for over two weeks during this "Summer War." [75] Peace was restored by late summer, but lost revenues could not be made up and D&RG receiver William S. Jackson found he could not afford any new projects until old debts were cleared.

If the Rio Grande was unable to undertake any improvements, another Colorado company nevertheless had started building toward west-central Colorado—the Colorado Midland Railway Company. Founded in 1883 by H. D. Fisher and other Colorado Springs businessmen, the corporation stalled until 1885 when James J. Hagerman, a Milwaukee ironmaster, joined the group as did Aspen's famed Jerome B. Wheeler. [76] The Midland was designed and built as a standard gauge line to more easily interchange with the major railroads of Colorado Springs and as such it was the first standard gauge line to penetrate Colorado's Rockies. The route entered the high country via Ute Pass west of Colorado Springs and proceeded on to Leadville via Trout Creek Pass. [77]

After serving notice on the D&RG that its mountain monopoly had ended, Midland management focused on Aspen and the mines of the Roaring Fork Valley. Hagerman and Wheeler no doubt supported this idea because of their extensive investments in the region. Original plans called for a line to be built south and west through the Saguache Range, approaching Aspen from the north. Workers bored a tunnel, the Hagerman Tunnel, through the Saguache Range beneath the pass of the same name. [78]

As the Midland's tracklayers moved toward Aspen in 1886, William S. Jackson sought and obtained permission from his stockholders and Receiver Moses Hallett for the Denver and Rio Grande to survey and begin construction on a line to Aspen. Work got underway immediately and an intense race for the silver traffic ensued. [79]

The narrow gauge company chose to follow the Eagle Valley to the Grand River, along that watercourse through Glenwood Canyon to Glenwood Springs and then up the Roaring Fork Valley into Aspen. Actual construction did not commence until January 1887, when Denver banker and mining magnate, David H. Moffat, Jr., took over as president of the D&RG. Over 600 tracklayers worked on the project. On October 4, 1887, section hands spiked down the last rails into Glenwood Springs and the next day a twenty car special arrived as the first train into town. Governor Alva Adams, Moffat, Walter Cheeseman, and other dignitaries were greeted by fireworks displays, electric lights, brass bands, shouting crowds, and Glenwood Springs Mayor P. Y. Thomas. At Hotel Glenwood, owner William Geilder, spread a banquet for the company. With dinner completed, a round of speech-making occurred, all in praise of Moffat, Jackson, the workers, the railroad, and whomever else could be congratulated. The festivities drew to a close in the small hours of the morning as the special returned to Denver. [80]

Not wasting time, D&RG crews started for Aspen soon after the Glenwood Springs festivities ended. Proceeding down the Roaring Fork Valley, tracklayers found their job easy compared to Glenwood Canyon. Buying parts of an old toll road near Carbondale to speed their efforts, Rio Grande management succeeded in reaching Aspen by the end of October, 1887. On November 1, the town held a celebration for the victors. Colorado Midland's effort stalled at Hagerman Tunnel, giving the race to the Denver and Rio Grande. [81] Aspen feelings about rail service were eloquently summarized at the celebration dinner in the following toast:

Then here's to our Aspen, her youth and her age, We welcome the railroad, say farewell to the stage, And whatever her lot and wherever we be; Here's forever God bless the D&RG. [82]

The railroad did not prove the blessing its Aspen supporters believed it would be. The company charged from $50 to $100 a ton for freight between Denver and Aspen. [83] After the Colorado Midland arrived in February 1888, competition forced rates down [84] and as CM tracklayers worked their way through Glenwood Springs and on to New Castle, a rate war ensued. The battle for passengers became so intense that one company offered free passage between Aspen and Glenwood Springs and to retaliate the other line not only offered a no-fare ticket but also paid one's admission to the hot springs pool at Glenwood Springs. [85]

Competitive pressures caused both railroads to look at the Grand Valley and again began a building race west toward Grand Junction. During 1889, a D&RG subsidiary, the Rio Grande and Pacific, extended narrow gauge trackage from Glenwood Springs west to Rifle, Colorado, so as to block the Colorado Midland from further westward construction. [86] Moffat, as president of the narrow gauge, purchased the Roan Creek Toll Road that same year for use as a right-of-way for a railway. [87]

The eighties construction race exhausted both companies' finances and in order to reach Grand Junction they entered into a joint agreement in December 1886, to build only one line. Colorado law would not allow competitors to rent trackage from one another so the Rio Grande Junction Railway was founded with the D&RG and CM as co-equal partners. [88] The Rifle-Grand Junction line was laid down as narrow gauge on standard gauge ties in preparation for conversion of the Denver and Rio Grande from three-foot gauge to standard gauge. [89]

During 1888, Moffat undertook to standard gauge the D&RG's mainline from Denver to Pueblo and then from Pueblo west via Leadville to Rifle. Many factors caused this. CM competition played a part as did the need to easily interchange traffic with railroads that ran east and south out of Denver. [90] Other improvements to the line included a tunnel below Tennessee Pass and the purchase of new equipment. [91] 1890 witnessed the extension of standard gauging west from Rifle to Grand Junction; arriving at the latter community on November 14. [92] Later that year, widening of the rails was completed to Utah and in a joint agreement with the Rio Grande Western the same process occurred to Salt Lake City. [93]

Moffat's tenure as president of the D&RG brought many changes for the railroad. His greatest vision went unfulfilled. During the late 1880s he had surveys made for a line to go directly west from Denver across the Continental Divide near Silver Plume, and then connect with the Grand River line thus shortening the Denver-Salt Lake City route by 150 miles. When Moffat laid his proposal before the Board of Directors in 1891, it was rejected as too expensive. The President then resigned and Edward T. Jeffrey replaced him as the D&RG's chief officer. Jeffrey believed in a policy of minimum expenditure. [94] The year before Hagerman had sold his control of the CM to the Santa Fe Railway because his funds were running dry during the great expansion race of the late 1880s. [95] Fortunately for west-central Colorado, the mainline railroads were finished before these changes in management occurred.

Throughout the 1880s, other companies examined the area looking for routes from Denver westward. Foremost among these was the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy (CB&Q) Railroad. In 1885, three years after reaching Denver, the Burlington announced plans to build a line from South Boulder Canyon into Middle park using a tunnel under James Peak and then go westward, possibly along the Grand River. The next year brought renewed talk of such a line with Burlington placing engineers in the Grand Valley looking at possible routes. However, little else came of this project. [96] Some evidence indicated that the company actually graded part of a route from Elk Creek to Glenwood Springs, but there are limited references to such an effort. [97]

Promoters of the Denver, Utah and Pacific also cast envious eyes on the Grand Valley during the eighties. Denver businessmen organized this road to build a system from Denver west via Rollins Pass to the Grand River or Yampa River and then west to Salt Lake City. Organizers included Horace Tabor and David H. Moffat, Jr. Some grading was done along the front range and near Rollins Pass but by 1887, the DU&P had passed into railroad history. [98]

The mines of the Roaring Fork attracted railroads like flies to sugar. In 1885, David Moffat organized the Denver, Aspen and Grand River Railroad Company to construct a line from the "Queen City" to the new silver camp and beyond to rich coal fields near Carbondale and the Huntsman Hills south of Glenwood Springs and then from there west along the Grand River to Grand Junction. Survey instructions included orders to locate the line near coal seams and mines; the promoters no doubt felt this was a good source of traffic. Surveys were conducted but no rail was ever laid. [99]

In 1899, another syndicate announced plans to build a railroad from Grand Junction west along the Grand River to its juncture with the Green River in Utah and then southwest down the Colorado River Valley to Southern California with a proposed terminus at San Diego. Plans called for a branch line to be built from Grand Junction to New Castle so that Colorado coal could be marketed in Southern California. That summer survey crews pushed west from Grand Junction, planning a route for the Denver, Colorado Canon and Pacific as the company was named. Problems during the survey, as well as lack of enthusiasm, resulted in the suspension of all operations. [100]

While these grandiose schemes were being hatched, other individuals worked hard building short lines to act as feeders for the D&RG and CM. W. T. Carpenter, an early settler of Grand Junction, filed claims on coal lands north and east of town near the Book Cliffs. He built the Little Book Cliffs Railway in 1890, a line of some 11 miles, to haul coal from his mines to the D&RG at Grand Junction. Throughout the 1890s, Carpenter fought a running battle with the Denver railroad over rate discrimination and lack of cooperation in handling interchange traffic. [101]

The Grand Junction mine operator and railroader was not immune to visions of grandeur so in 1895, he organized the Colorado, Wyoming and Great Northern Railway to connect Grand Junction with the Union Pacific Railroad at Rawlins, Wyoming. Throughout that summer Carpenter tried to raise funds, with some success, but disagreements with investors dissolved the corporation in August 1895, after only small amounts of grading were finished. [102] Four years later, Carpenter sold the Little Book Cliffs Railroad to the Book Cliffs Railway Company that operated the line until 1920. After five years of standing idle, the tracks were torn up in 1925. [103]

Many other builders used the connection of mines with major railroads as the rationale for their dream. Aspen, in particular, enjoyed a multitude of such lines. During the closing years of the 1880s, years noted for the silver mining boom, the Aspen Mountain Railroad Company, the Aspen and Southern Railroad, the Aspen and Ashcroft Railroad, and the Aspen Public Tramway all were organized to run between various mines and either the D&RG or the CM. In 1893, the Aspen and Maroon Railway surveyed a course to Maroon Creek but, as with many of these projects, no track was ever laid. [104]

West of Aspen, in the Roaring Fork Valley, was the Crystal River Valley which offered entrepreneurs more opportunities in railroad building, as the valley formed a natural route south to McClure Pass and easy access to mineral deposits at Coal Basin and on Thompson Creek. The Aspen and Western was the first company to successfully build into the area. Incorporated in 1886, its charter called for a line between Carbondale and the head of Thompson Creek and from there to proceed in a generally western direction, possibly as far as Grand Junction or Utah. [105]

By 1888, tracklayers had placed 13 miles of narrow gauge railway up Thompson Creek to coal mines owned by Colorado Coal and Iron Company. The mines proved not to be great producers and the line closed after only a few years of operation. In 1892, it changed hands as part of John C. Osgood's purchase of Colorado Coal and Iron. Using the Aspen and Western as a base, Osgood founded the Crystal River Railway Company to extend a line south along the Crystal River Valley to Coal Basin as well as other lines to Glenwood Springs, New Castle, Harvey Gap, and Grand Junction. [106] As mentioned earlier, the Panic of 1893 and silver slump forced Osgood to postpone his plans for the Crystal River route. [107]

As the money supply returned toward the end of the nineties, Osgood revitalized his plans including a rail line. In 1898, the Crystal River Railroad Company, formed as a subsidiary of Colorado Fuel and Iron, announced plans to build from Carbondale to Placita by way of Redstone. At Redstone a branch line connected that town with Coal Basin. The route from Carbondale to Placita was standard gauge, however, narrow gauge was used between Redstone and Coal Basin, with dual gauge yards at Redstone. Rails were in place and the road was operational by 1900. [108]

After Osgood lost control of Colorado Fuel and Iron Company in 1903, the railroad changed hands and three years later was re-organized as the Crystal River and San Juan Railway. The new owners, primarily Colorado-Yule Marble Company, extended the line south to Marble. As an auxiliary to the railroad, Colorado-Yule Marble built an electric tramway from town to the quarry. These rail lines remained in more or less continuous operation until 1941. [109] The dawn of the twentieth century witnessed many new rail projects started throughout the district.

In a further effort to increase Aspen's rail service, the Taylor Park Railroad Company was founded in 1901 to connect Gunnison and Aspen. New silver discoveries during 1900 in Taylor Park led to a rush of miners and railroaders. The idea of a railroad into Taylor Park began in 1879, but no action occurred until the twentieth century. Tracklayers laid a few miles of line near Aspen but the deposits played out quickly and four years after organization the company was disbanded. [110]

During the same period, the electric railway's popularity grew throughout the nation. From 1906 to 1910, citizens of towns such as Fruita complained of needing an electrified train or interurban, as they were known. Such lines allowed for low cost operations and proved ideal for brief runs between neighboring towns. The first attempted interurban in the valley began in 1905 when the Mesa County Traction Company proposed to build from Grand Junction to Colbran and then to the Utah state line. The project failed. [111] In 1908, the Grand Junction Electric Railway Company announced plans to build from Grand Junction northeast to Palisade and northwest to Fruita. The next year the company reorganized as the Grand Junction and Grand River Railway. By July 1910, cars were running over the lines to Fruita and Palisade. [112] At approximately the same time, other financiers set up the Grand River Valley Electric Railway, commonly referred to as the "Fruit Belt." In 1909, this company succeeded in building a line from Grand Junction to Fruita and operated until 1935. [113]

As the interurban craze swept the nation, coincidental to the Good Roads Movement, demand for road paving material increased sharply. To help satisfy a need, roads began to use asphalt, of which gilsonite constituted a basic ingredient. First discovered in 1884 in Utah by Samuel Gilson, commercial mines did not open until the late eighties. [114] Development of the mines depended on cheap and fast transportation because wagons were too slow and costly. [115]

The problem was solved when William N. Vaile and his associates, on behalf of the General Asphalt Company, earlier known as the Barber Asphalt Co., incorporated the Uintah Railway on November 4, 1903. [116] The road was planned to run from Mack, Colorado, on the Denver and Rio Grande north-northwest along West Salt and Evacuation Creeks to Utah and the Dragon Gilsonite fields. Built as a narrow gauge railroad, it had the distinction of being one of the last such railways built in the United States. [117] C. O. Baxter, for whom Baxter Pass was named, planned the route to haul gilsonite and it included some of the heaviest grades and sharpest curves of any rail line in North America. [118]

Construction took two years. During 1905 the line opened for business. Mack, Colorado, built solely for the railroad, became a shipping center where crews transferred gilsonite from narrow gauge to standard gauge cars. The Uintah Railway hotel and general headquarters were also located there. All this rail activity stimulated business activity in neighboring communities, especially Fruita. Eventually this town became the site of a large gilsonite refinery. [119]

From Mack to the crest of Baxter Pass the Uintah encountered all varieties of terrain, especially the difficulties in climbing atop the Roan Cliffs from the Grand Valley, some 3,900 feet below. Parts of the route between Atchee and Baxter Pass had almost 6 miles of 7.5 percent grade. In 1924, the Interstate Commerce Commission said the Uintah had some of the most difficult railroading in the United States. [120]

|

| The Uintah Railway provided the only north-south connections from Grand Junction and served northeastern Utah until the late 1930s. Photo by Museum of Western Colorado |

To alleviate operating expenses, Uintah planners decided to open their own coal mines as a supply of fuel. Seams were found along the route and mines started to operate at Carbonera, Colorado. The town, located 20 miles north of Mack, in Garfield County, remained small and was used only by the railroad. [121]

To keep their equipment running, the company established locomotive shops and a car repair facility at Atchee, Colorado, another town built by the Uintah. Located in Y-shaped canyon, Atchee, named after a Ute chief, also served as a locomotive changing point because the engines that brought trains to and from Mack could not negotiate the grades and curves west of Atchee. At its height, the town housed over 100 people, but being so closely tied with the railroad its fortunes matched those of the Uintah. When slurry pipelines replaced the railway in 1938, and it ceased to exist, so did the town. [122]

Uintah management, in 1911, determined to extend the line from Dragon, Utah, to Watson, Utah. Contemporary rumors in Grand Junction and Fruita contended that once the extension was completed, there was a serious plan by A. E. Carlton, Cripple Creek magnate, to connect the Midland with the Uintah by using his Grand River Valley Railway (an interurban) to form the final link. Citizens of Vernal, Utah also talked of the possibility of Uintah rails reaching their town. Most of this proved to be wishful thinking. The Gilsonite Road did build from Dragon to Watson (Rainbow mine) but that was as far west as it ever got. [123]

To provide points such as Vernal or Rangely, Colorado transportation, the rail company established the Uintah Toll Road Company as well as a freight wagon and stage service. This was cheaper than building more track and served the region's needs adequately by acting as a feeder to the rail line. [124]

The Uintah eloquently testified to the problems faced by rail companies throughout west-central Colorado. While the 7.5 percent grades of Baxter Pass were unusually heavy, the terrain presented problems for all railroads, especially trying to find useable passes. Often when a route could not be found one had to be created by blasting tunnels through the mountains. Both the Denver and Rio Grande and the Colorado Midland bored under the Continental Divide at great expense. [125] Because river valleys offered the course of least resistance, and haste was the builder's watchword, often the tracks were laid too near streams and washed out during heavy rains or in spring run-offs. [126]

As if natural problems were not enough, the carriers soon found themselves besieged by angry patrons. Every town and nearly every person wanted railroads but once service was established, the steam cars proved not to be the panacea envisioned. When the D&RG first arrived at Grand Junction the entire town, including a Chinese laundryman, felt that a new day had dawned and prosperity assured. [127] Within ten years, many of these same Grand Junctionites complained of unfair rates, discrimination among shippers, and generally viewed the railroads as the source of their economic woes. The carriers were guilty of some misdeeds such as charging the same to haul goods from Denver to Salt Lake City as Denver to Grand Junction. However, this was due in large part to the competitive nature of Salt Lake City's market in comparison to Grand Junction's. Nevertheless public outcry did reach the state legislature which soon investigated rate structures. This exposure forced the D&RG to lower its Grand Junction tariffs during the early twentieth century. [128]

The new century brought change to west-central Colorado's railroads. Old routes were modernized and operations were abandoned while one new mainline made its presence felt.

The Denver and Rio Grande came under the control of George Gould, rail entrepreneur and the son of Jay Gould. George Gould, in 1900, set out to create a coast-to coast rail network. To do so he bought control of the Denver and Rio Grande Western in 1901. As part of Gould's improvements, the branchline from Montrose to Grand Junction was converted to standard gauge. The D&RG and RGW merged informally into the Denver and Rio Grande Western but due to financial distress the union was not completed. Gould's building of the Western Pacific Railroad from Salt Lake City to California drained his wealth and the Colorado companies went into receivership. A reorganization committee, without Gould, completed its work and in 1920, and the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railway Company emerged financially stronger than before. [129]

The area's other major railroad, the Midland, unable to profitably compete, went out of business by 1920. As mentioned, A. E. Carlton owned the Midland during the early twentieth century. He hoped to operate it efficiently, but even with the added business of World War I the company operated in the red. In 1918, the Interstate Commerce Commission held abandonment hearings and granted permission for cessation of business despite protest all over west-central Colorado. The next year, tracks were taken up and the roadbed converted for auto use, parts of which near Basalt are still used. [130]

In 1902, while the D&RG and Midland faced hard times, a new mainline road announced plans to build from Denver to Salt Lake City. David H. Moffat, Denver promoter since 1860, backed this new line, called the Denver, Northwestern and Pacific. Moffat had long sought a direct east-west transmontane railroad for Denver and, in frustration, finally determined to build such a line himself. DNW&P engineers laid out a route from Denver into South Boulder Canyon over Rollins Pass down to Middle Park and then north up the Yampa River to Steamboat Springs, west to Craig and then on to Salt Lake City. The road only slightly touched the northeast corner of west-central Colorado. and pushed the tracks over Rollins Pass and well into Gore Canyon. With help from other Denver financiers, the road reached Steamboat Springs in 1908, while new financial arrangements were made.

The Moffat Road, as the DNW&P was called, planned to tunnel under the Continental Divide at James Peak and open a new route to Salt Lake City that would by-pass Glenwood Springs and Grand Junction. This worried the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce because such a route would cost them trade and threaten their position as "capital" of the Western Slope. However, DNW&P passed within 35 miles of the D&RG mainline at Dotsero, making the possibility of a connection feasible. West-central Coloradans felt such a link would improve their rail service and protect their position vis a vis the rest of the state. David Moffat died in 1911, and two years later the road stalled at Craig. By 1920, the hopes and fears the line brought remained dead. [131]

West-central Colorado's transportation network rapidly expanded from 1880 to 1900. The region was well serviced by wagon roads and railways operating in a complimentary manner. Mining attracted some of the commerceways, while others crossed the area in search of other riches. Nevertheless, the existence of these highways and railroads stimulated all types of economic activity in the region.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

co/12/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 31-Oct-2008