![]()

Five Views: An Ethnic Historic Site Survey for California

MENU

Introduction

pre-1769

![]() 1769-1848

1769-1848

1849-1879

1880-1904

1905-1933

1934-1964

1965-1980

Historic Sites

Selected References

A History of American Indians in California:

1769-1848

On July 16, 1769, the Spanish founded the first mission in California. It has been estimated that there were about 310,000 Indians living in California at the time. (Cook, 1962:92) However, over the next 80 years, this number was to change drastically, along with the lifestyle and culture of the Indians.

"Spain's Indian policy at the time of the invasion of California was a mixture of economic, military, political, and religious motives. Indians were regarded by the Spanish government as subjects of the Crown and human beings capable of receiving the sacraments of Christianity." (Heizer, 1978:100) "It was essential under 'missionization' that California Indians be 'reduced' into settled and stable communities where they would become good subjects of the King and children of God. Missionization required a brutal lifestyle akin in several respects to the forced movement of black people from Africa to the American South." (Archibold, 1978:172) Thus, "it should be clear, then, that the missions of California were not solely religious institutions. They were, on the contrary, instruments designed to bring about a total change in culture in a brief period of time." (Forbes, 1969:29)

The missions were built with Indian labor. This seems ironic given the devastating effect the mission system had on Indian population and culture, but it must be remembered that the Spanish saw the Indian neophytes (a neophyte is a new religious convert) as "little more than an energy source which cost nothing to acquire and nothing to maintain — they were an expendable resource. If the mission system had been progressive, if the priests (and the Mexican Presidents) had been able to learn from observation and experience, and thus allow changes to occur which would have been accommodations to problems of managing the neophyte populations, then there could have developed an operation which would have become more humane, and more consistent with doctrinal theory." (Banning, 1978:136)

From 1769 to 1800, the California coast was under Spanish control from as far north as San Francisco to San Diego in the south. However, this was not accomplished without a certain amount of resistance. Within a month after establishment of the San Diego mission in 1769, the Indians "attacked the Spanish camp, attempting to drive the invaders from their territory. But the Spanish soldiers, using guns, defended their settlement and an uneasy peace ensued. Yet, it would be another two years before Mission San Diego could record its first baptism." (Heizer, 1978:101)

Throughout the mission period, Indians resisted Spanish rule. "One of the earliest and most successful demonstrations of native resistance to colonization was the destruction of Mission San Diego on November 4, 1775. Under the leadership of the neophyte Francisco of the Cuiamac Rancheria, the Ipai-Tipai organized nine villages into a force of about 800 men who not only completely destroyed the mission but also killed three Hispanos including Padre Jaime." (Heizer, 1978:103)

Not every resistance effort was violent. "The natives, Christian and gentile, caused more trouble in the region of San Francisco than in any other part of California. . . . In September of the same year 1795 over two hundred natives deserted from San Francisco, different parties in different directions, the number including many old neophytes who had always been faithful before." (Bancroft, 1963:708-709) Resistance occurred throughout the mission period, but the clerico-military administration did not tolerate even non-violent resistance. They responded by attempting to prevent escapes, sending out armed parties to capture runaways, and punishing recaptured runaways.

When Indians did resist, they did not go unpunished; in many instances, it was punishment that caused the resistance. "Perhaps the most spectacular Indian rebellion in California during this era was the 1824 revolt at Missions La Purisima and Santa Barbara. The reason for the revolt was ill treatment and forced labor imposed by the soldiers and priests upon neophytes in the area, but the immediate cause was a fight that broke out at the flogging of a La Purisima neophyte at Santa Ynez in February. Apparently no one was killed but a large part of the mission buildings was destroyed by fire. That same afternoon as many as 2,000 Indians attacked and captured Mission La Purisima. . . . It was not until March 16 that the Spanish soldiers attacked the 400 defenders at La Purisima with hundreds of armed and mounted men and four pounder guns." (Heizer, 1978:103) The Indians who led the rebellion were punished. Seven Indians were put to death, while many others were imprisoned and required to do hard labor.

Another form of resistance involved the retention of native religious activities. "In general, the natives did their best to secretly preserve their ancient religion in the missions, although it became increasingly difficult to do so. Native revivals are known to have occurred as in the Santa Barbara area in 1801." (Forbes, 1969:35)

In looking at the mission system, it is easy to understand why the Indians resisted. In 1786, Jean Francois Galaup de La Perouse, a French navigator, made the following report. On the way into church, he passed a place where Indians were seated in rows by sex. "We repassed, on going out of church, the same row of male and female Indians, who had never quitted their post during Te Deum; the children only had removed a little. . . . On the right stands the Indian Village, consisting of about fifty cabins, which serve as dwelling places to seven hundred and forty persons of both sexes, comprising their children, which compose the mission. . . . These cabins are the most miserable that are to be met among any people; they are round, six feet in diameter by four in height. . . . The men and women are assembled by the sound of the bell. One of the religious conducts them to their work, to church, and to all their other exercises. We mention it with pain, the resemblance so perfect, that we saw men and women loaded with irons, others in the stocks; and at length the noise of the strokes of a whip struck our ears, this punishment being also admitted, but not exercised with much severity." (Fehrenbacher, 1964:100-101) Whether or not the flogging was exercised with "severity" is not the point, but rather, was this form of punishment necessary?

In 1799, Padre Antonio de la Concepcion Horra of Mission San Miguel enraged his contemporaries by reporting to the viceroy in Mexico, "'The treatment shown to the Indians is the most cruel I have ever read in history. For the slightest things, they receive heavy flogging, are shackeled and put in the stocks, and treated with so much cruelty that they are kept whole days without water.' The unfortunate padre was quickly isolated, declared insane, and taken under armed guard out of California." (Heizer, 1978:102) Other conditions that made the mission intolerable to the Indians included overcrowding, lack of native foods, and the weather (especially for inland Indians who were required to live on the coast for the entire year).

During the mission period, disease played a significant role in the reduction of the native population. Three major epidemics broke out during the Spanish period. In 1777, there was a respiratory epidemic; in 1802, a pneumonia and diphtheria epidemic; and in 1806, a measles epidemic. However, diseases were not the only cause for the rapid decline of the Indian population while under mission rule. Much of the decline can be attributed to changes in diet and inadequate nutrition. (Heizer, 1978:102-103) In 1818, Governor Vicente de Sola reported that 64,000 Indians had been baptized, and that 41,000 were dead. (Forbes, 1969:37)

Not everything was negative under Spanish and Mexican rule. In 1824, the constitution guaranteed citizenship to "all persons." While neither the Spanish nor the Mexicans acknowledged Indian land ownership, they did provide the natives with the right to continue to occupy their villages. Indians were also introduced to farming, and although both farming and cattle grazing had a devastating effect on the native habitat, the farming experience itself provided Indians with the skills necessary to survive in the upcoming years. During this period, many native people also learned crafts that helped them find employment once the Americans arrived.

Following Mexico's independence from Spain in 1821, there was a shift in the entire approach to Indian policy taken by the government. "In 1825 Lt. Col. Jose Maria Echeandia was appointed in Mexico to be governor of California and when he came north he brought with him new ideas of Mexican republicanism. . . . He also wished to abolish the missions. . . . In 1834-1836 Governor Jose Figueroa was finally forced by the Mexican government . . . to commence the formal secularization of the missions." (Forbes, 1969:39) The process of secularization provided that one half of the mission property would go to support the Indians, and half to support the priests and other officials. During this time, "the entire economy of the Mexican colony now shifted from the missions to the large landed estates of wealthy Mexicans." (Heizer, 1978:105)

As government emphasis changed from a mission approach to private enterprise, large land grants were given to Mexican citizens. This was necessary in order to put additional lands under Mexican rule. Naturalized citizens including John Marsh, John Sutter, John Bidwell, and others were awarded large land grants to settle for Mexico. "During the years 1830 to 1846 the interior native population suffered more extensively from brutality and violence than might perhaps be anticipated. Violence was a critical factor among tribes that resisted. . . One such filibustering expedition was led by Jose Maria Amador in 1837. . . According to Amador, his party:

'. . . invited the wild Indians and their Christian companions to come and have a feast of pinole and dried meat . . . the troops, the civilians, and the auxiliaries surrounded them and tied them up . . . we separated 100 Christians. At every half mile or mile we put six of them on their knees to say their prayers, making them understand that they were about to die. Each one was shot with four arrows. . . . Those who refused to die immediately were killed with spears. . . . We baptized all the Indians (non-Christians) and afterward they were shot in the back.'" (Heizer, 1978:105-106)

However, disease had a much greater effect on Indians than any act of violence. During this period, smallpox and scarlet fever had a devastating effect on the native population, killing thousands.

With the ranchos came a need for a labor force. Much like the missions, the ranchos used Indians to meet this need. Major landowners took advantage of the lack of unity among Indian groups. For example, they would make pacts with one Indian group, then require them to bring in other Indians to serve as laborers. Once the landowners had organized their labor force, they would exchange labor with other ranchers. Thus developed a system of labor that was virtually cost-free.

Another example of how Mexican landowners worked this labor system to their advantage is the case of Charles Weber. In 1845, Weber purchased William Gulnac's interest in a ranch in the area now known as Stockton. For 200 pesos, Weber purchased the land which Gulnac could not settle because of Indian resistance. On his arrival, he employed the same system John Sutter had used and made a pact with an Indian leader, Jose Jesus, an ex-mission neophyte. Jesus provided Weber with labor in exchange for goods. This type of arrangement became increasingly advantageous to Indians, because if they did not enter into a pact, the landowners would raid their villages and take the labor they needed anyway.

In February 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ceded sovereignty of Mexican lands, including California, to the United States. However, before the constitutional ideology of the American government could take effect here, the discovery of gold turned California into a land of confusion. After James Marshall's initial discovery, John Sutter and Charles Weber used Indians to mine the precious ore. As news of the discovery spread and more Europeans arrived in California, the Indians were soon forced out of mining. Initially, a group of men from Oregon ran the Indians out of the mines because they believed the jobs rightfully belonged to White men. With the miners' search for gold, the Sierra and other remote areas where Indians had retreated became prime locations for establishing claims. The dramatic rise in the White population during this era all but ensured the end of the claim to California by the Indians.

In summary, this era saw the beginning and the end of the mission period. Because of disease, homocide, and loss of their native environment and food sources, the Indian population in California decreased from 310,000 to approximately 100,000. With the secularization of the missions, the Indians were confronted with new problems of private ownership. In 1848, California came under the authority of the United States, and just as the Indians were becoming accustomed to the rancho system, the gold rush brought about a new era of Indian-settler relations.

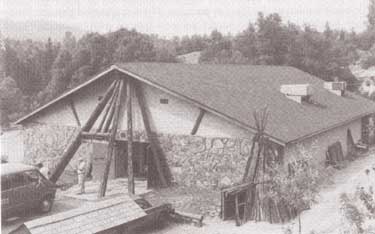

Sierra Mono Museum, Madera County

NEXT> 1849-1879

Last Modified: Wed, Nov 17 2004 10:00:00 pm PDT

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/5views/5views1b.htm

![]()

Top

Top