Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Philosophical Underpinnings

of the National Park Idea

Dwight T. Pitcaithley

Chief Historian

National Park Service

Copyright © 2001 by the Association of National Park Rangers. All rights reserved. This article is republished from Ranger, Fall 2001, with permission from the Association of National Park Rangers.

Wallace Stegner, that insightful observer of the American West, liked to remark that the idea of national parks was the best idea we ever had. He believed that the concept of national parks was inevitable "as soon as Americans learned to confront the wild continent not with fear and cupidity but with delight, wonder, and awe." Inevitable or not, the idea gradually took form from multiple threads. The artist George Catlin first articulated the idea of large western national parks in 1832, the same year Congress set aside the Hot Springs Reservation in central Arkansas, now known as Hot Springs National Park. On a trip to the Dakotas Catlin worried about the impact of America's westward expansion on Indian civilization, wildlife and wilderness. They might be preserved, he wrote, "by some great protecting policy of government . . . in a magnificent park . . . A nation's park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature's beauty!"

Artist George Catlin first articulated the idea of large western national parks in 1832

Lawyer, writer and philosopher Joseph Sax has given us perhaps the most comprehensive and articulate assessment of the growth of the idea in an article titled, "America's National Parks: Their Principles, Purposes and Prospects."

One thread, according to Sax, was the growing belief, by the midpoint of the 19th century, that spectacular natural areas could be quickly and profoundly despoiled. Beginning in 1806, developers bought land adjacent to Niagara Falls for industrial and tourism purposes. By 1860, the famous falls were so congested with haphazard development that the area had become the prime example of how a scenic wonder should not be developed.

Photo courtesy of Association of National Park Rangers, Copyright © 2001. |

The earliest and clearest articulation of a philosophy for the use and enjoyment of public pleasuring grounds came several decades after Catlin, but long before President Woodrow Wilson established the National Park Service in 1916. In 1864 Abraham Lincoln authorized the transfer of the Yosemite Valley to the state of California for "public use, resort and recreation." Frederick Law Olmsted was appointed chairman of the board of commissioners established to oversee the administration of the park, and he formulated a theory of use for this new type of land. The national park idea took root in an 1865 report that presented his views on how Yosemite should be developed.

Olmsted, the preeminent landscape architect of the 19th century, presented more than a theory of use, he articulated a philosophy of leisure based on nature's regenerative powers for an urbanizing society. He believed, this builder of Central Park in New York City and countless other urban parks throughout the country, that the essence of park land should be in establishing a contrast to the pace of the modern world. Anchoring his thinking at the conclusion of the Civil War and amid the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, Olmsted envisioned a need for ordinary citizens to maintain perspective in their daily lives by being exposed to, and encouraged to contemplate, the natural rhythms of the natural world.

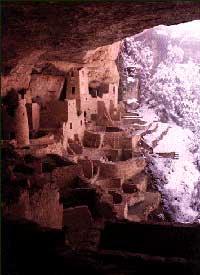

Olmsted wrote during a period in American history when American society was eager to find ways to measure up to European society. Before the 1860s and 1870s, North America had nothing to compare to the Swiss Alps or the antiquities of Rome or the canals and museums of Venice. Americans who took the "Grand Tour" to experience the sights and culture of Europe did so because there was no equivalent in the United States. (It would be several decades before the wonders of Mesa Verde or Chaco Canyon would be revealed to the American public.) The grandeur and spectacle of the Yosemite Valley and the sequoia trees of the Mariposa Grove, however, were something else. Therein was scenery that could compare favorably with the best Europe had to offer.

|

Olmsted was not an advocate of wilderness, rather he thought it most appropriate that parks have restaurants and hotels and carriage paths and trails so that a leisurely appreciation of nature was possible. How else could men and women of leisure enjoy the sights and scenery of these grand places? These conveniences, however, should not interfere, visually or audibly, with the process of appreciation. This policy of recreation, in the words of Joseph Sax, "of testing the importance of one's daily tasks against some permanent standard of value," was at the heart of Olmsted's philosophy. It was contrast Olmsted was after, contrast of the rhythm and pace of a daily existence with the rhythm of the natural world. "We want a ground," he wrote, "to which people may easily go after their day's work is done . . . we want . . . the greatest possible contrast with the restraining and confining conditions of the town . . . we want . . . tranquility and rest to the mind. With this thought in mind, Olmsted constructed many of the nations most significant urban parks. It was not a stretch, then, for Olmsted to adopt the same philosophy of contrast for Yosemite. The Mariposa Grove was not as accessible to the working class at the end of the day, but the park did carry the concept of contrast to its logical conclusion.

Later, the founding fathers of the NPS made clean distinctions between the conservation of "scenery and . . . natural and historic objects" and the "enjoyment of the same." Although pleasure and enjoyment were seen as byproducts of recreational use of parks, enjoyment was also to be derived through education. "The educational, as well as the recreational, use of the national parks," Secretary Lane wrote to Stephen T. Mather in 1918, "should be encouraged in every practicable way." The connections between parks and learning, formal and informal, constitute another philosophical thread, and were recognized early as an important element in the purpose of parks.

Olmsted, as noted, wrote from the vantage point of mid-19th century America near the end of the American Civil War, at the same time, interestingly enough, as George Perkins Marsh was developing his pioneering work on conservation, Man and Nature. The country was different then. The nation's population stood at a mere 31 million. Most of the West, with the notable exception of parts of California, Colorado, Nevada and New Mexico, was still occupied only by scattered Indian peoples. By the time Congress established the NPS in 1916 the population had multiplied threefold, and by 1960 it had grown almost tenfold to 180 million! The spatial relationship between towns and cities and uninhabited sections of the country was different 100 years after Olmsted's report on the Mariposa Grove. Wild places were shrinking and becoming more precious. The sense of place with which Americans viewed Yosemite and Yellowstone was different. The manner with which Americans viewed their environment had also changed. The change was reflected in a flurry of legislation that affected the management of the National Park System as much as it recognized this country's commitment to environmental health. By the 1960s, population and development pressures throughout the country resulted in the passage of the Wilderness Act (1964), National Historic Preservation Act (1966), Clean Air Act (1967), Wild and Scenic Rivers Act (1968), National Environmental Policy Act (1969), and the Endangered Species Act in 1973. The country had changed and so would the NPS as it implemented these and other laws, and recognized the global implications of its actions.

|

Another factor affecting the philosophical framework of the Service present from the beginning, but expanded and clarified over time was the emphasis placed on the preservation of cultural resources. Even before the establishment of the NPS, Congress and the President (through the authority of the 1906 Antiquities Act) began to define a national policy of historic preservation as they recognized the nationally significant values of Casa Grande, Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon, Gran Quivira, and Sitka among others. Subsequent legislation such as the 1935 Historic Sites Act, the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, and Archeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 further enhanced the Service's philosophical (and legal) underpinnings in the area currently identified as heritage preservation. (Additional philosophical expansions resulted from the creation of numerous preservation and technical assistance programs Congress authorized over time in the areas of historic preservation, recreation, and open space conservation.)

The philosophy of national park management is now more expansive, and certainly more complex, than it was in either 1865 or 1916, but it continues to revolve around the protection and preservation of cultural and natural resources. While it has not been entirely consistent on this point through the decades, the Service is mindful of its responsibility to manage resources with care and thoughtfulness sufficient to leave them unimpaired for future generations. That attentiveness to preservation and its co-mandate in the 1916 Organic Act, "enjoyment," has led the Service to revisit continuously the philosophy of managing national parks, and to ensure a clear understanding of the Service's legislative mandates. The latest version of the Management Policies (2001) represents the current evolution of that thinking and should be required reading for all interested in understanding the practical implications of the philosophical structure that guides the management of parks. As the Policies have tried to make clear, the philosophy of park management stems not only from key aspects of the Service's history — Olmsted's thinking, Yellowstone's founding, Stephen T. Mather's passion — but from the subsequent laws and proclamations passed by Congress and issued by presidents. The governing philosophy of the NPS is more complex these days because the society in which it operates is more complex. The population of the United States now stands at 280 million, almost 10 times that when Olmsted articulated his philosophy of leisure during the 1860s. And yet, the Service still provides a sense of contrast, of wonder, of awe, at cultural and natural sites alike.

Somewhere between the prose of Congress and the poetry of Stegner lies the philosophical soul of the National Park Service.

Congress and Wallace Stegner, not surprisingly, had different ways of capturing the values of the Service and System. In 1970, and again in 1978, Congress summed up its 100-year history of setting aside special places by stating that the parks that comprise the National Park System "are united through their interrelated purposes and resources into one national park system as cumulative expressions of a single national heritage; that, individually and collectively, these areas derive increased national dignity and recognition of their superlative environmental quality through their inclusion jointly with each other in one national park system preserved and managed for the benefit and inspiration of all the people of the United States," . . . and that all management activities "shall be conducted in light of the high public value and integrity of the National Park System and shall not be exercised in derogation of the values and purposes for which these various areas have been established."

A decade earlier, Stegner mused with his poet's heart on the preservation of wild space:

We need wilderness preserved because it was the challenge against which our character as a people was formed. The reminder and the reassurance that it is still there is good for our spiritual health even if we never once in ten years set foot in it. It is good for us when we are young, because of the incomparable sanity it can bring briefly, as vacation and rest, into our insane lives. It is important to us when we are old simply because it is there — important, that is, simply as idea . . . We simply need that wild country available to us, even if we never do more than drive to its edge and look in. For it can be a means of reassuring ourselves of our sanity as creatures, a part of the geography of hope.

Somewhere between the prose of Congress and the poetry of Stegner lies the philosophical soul of the National Park Service.

Suggested readings

Wallace Stegner, "The Best Idea We Ever Had," in Marking the Sparrow's Fall: The Making of the American West. Edited by Page Stegner. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1998, p. 137.

Joseph L. Sax, "America's National Parks: Their Principles, Purposes, and Prospects," in Natural History (October 1976), pp. 59-87.

Dwight T. Pitcaithley, "A Dignified Exploitation: The Growth of Tourism in the National Parks," in Seeing and Being Seen: Tourism in the American West, edited by David M. Wrobel and Patrick T. Long. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

The growth of the National Park System is detailed in Barry Mackintosh, "The National Parks: Shaping the System." The most current edition of Shaping the System is found only on the Web.

Dwight T. Pitcaithley is the chief historian of the National Park Service. He began his NPS career as a seasonal laborer during the summer of 1963. In 1976 he was hired as a research historian in the Southwest Regional Office in Santa Fe and later became the regional historian in the Boston regional office. He served as chief of cultural resources in the National Capital Region before becoming chief historian in 1995.

return

to Thinking About National Park Service History page