THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LOOKS TOWARD THE

21ST CENTURY: THE 1988 GENERAL SUPERINTENDENTS

CONFERENCE AND DISCOVERY 2000

Janet A. McDonnell

January 2001

INTRODUCTION

In 1988 and 2000, the National Park Service held major Service-wide conferences — the first with the broad theme "Planning for the 21st Century" and the second to shape a vision for the 21st Century. The first one was held in the wonderfully scenic environment of Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming and the second one, twelve years later, in the shadow of St. Louis' soaring arch. Each conference provides a "snapshot" of the Park Service at the time — its people, its programs, its priorities, and its values. The meeting in St. Louis opened with a stirring video presentation that posed the questions "Who are we?" and "What do we value?" And to some extent, both conferences tell us something about how the Park Service grappled with these fundamental questions.

Although both conferences were convened to address the future of the Park Service, they differed in their setting, format, organization, goals, and purpose. The "general superintendents conference" at Jackson Lake Lodge in Grand Teton National Park was a traditional superintendents conference. Most of the 500-plus participants were park superintendents or assistant superintendents. The second conference called "Discovery 2000" at the Regal Riverfront Hotel in St. Louis, Missouri, was larger, more inclusive, more representative of the Park Service as a whole, and specifically designed to include "partners" who work with the Service to carry out the larger common mission. By 1999 Park Service Director Robert Stanton had recognized the need to shift from a traditional superintendents conference to a different, more inclusive kind of meeting. Discovery 2000 was twice the size of the Grand Teton conference with more than 1200 participants. In addition to superintendents and assistant superintendents, this unique conference included large numbers of cultural resource specialists, archeologists, anthropologists, and interpreters. It also included approximately 200 Park Service employees carefully selected as potential leaders in the next century. The participants included a broader mix of Park Service Washington and regional office staff, and representatives from various federal, state, and local agencies, Indian tribes, concessionaires, non-profit organizations, and foreign parks. Less than 25 percent of the participants were park superintendents, and only 70 percent of participants were Park Service members. [1]

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial |

The format of the conferences varied. At Grand Teton National Park, participants spent most of their time each day in large plenary sessions listening to speakers, and though Discovery 2000 included plenary sessions, it was characterized more by approximately 140 smaller group sessions and workshops designed to stimulate creative thought and discussion. The 1988 conference provided more opportunities for relaxation and informal interaction than Discovery 2000. It included a barbecue, wine tasting, art auction, a book-signing for former Park Service Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., an art raffle, a print-signing session with artist Morton Solberg, and a free afternoon for participants to hike, raft, and enjoy the park. With over a decade past since the last superintendents gathering, the conference at times took on the flavor of a family reunion. Discovery 2000 included a few evening activities: an opening reception at the Gateway Arch, a street fair at the Laclede's Landing National Register Historic District, and a baseball night at Busch Stadium. Park Service members who attended both conferences observed that Grand Teton National Park offered a more relaxed setting than St. Louis. There were more group meals and activities at the park and more opportunities for informal discussions. The Jackson Lake Lodge with its vast lobby and outside terrace was particularly well-suited for these informal interactions. Participants were invited to bring family members to the conference, at their own expense.

Discovery 2000 was more intense and perhaps more intellectually demanding on participants. Planners hoped to inspire and extract "the best thought of each individual participant regarding the long-range future." In the months before the conference, they sent messages to each participant encouraging them to prepare mentally. To encourage advance preparation, they distributed a reading list as well as documents called "Duties of a Session Leader" and "Duties of a Participant." Planners kept after-hours social events to a minimum because they believed those activities were inconsistent with their goal of a "hard-working" conference. [2]

The St. Louis conference incorporated some unique features. There were scheduled journal writing sessions to encourage participants to record their thoughts, perceptions, and experiences. Conference planners set up a time capsule where participants were encouraged to express their visions for the Park Service. Reflecting the tremendous technological advances of the 1990s, conference organizers established a specially designed "Discovery 2000" internet web site that participants could use to register for the conference and get other important conference information. The web site also allowed "virtual participants" to receive the most current information about the conference. Remarks by the keynote speakers, summaries of the sessions, the daily conference newsletter, and media reports were posted throughout the conference. Even after the conference ended, organizers continued to use the web site as a tool for communicating with participants.

Another unique feature at Discovery 2000 was the "Expo 2000 Trade Show." The trade show, sponsored by the Jefferson National Parks Association, consisted of nearly 80 exhibit spaces for a variety of commercial vendors, non-profit organizations, and National Park Service programs. It was designed as a marketplace for new and innovative technologies, methods, and programs to help Park Service managers and their partners "better cope with the 21st century." "The idea was to have Expo be more than just a collection of vendors and program offices, but a group of displays that would mirror the forward-looking aspects of this conference," said Gary Cummins, Harpers Ferry Center Manager. There was a greater emphasis on environmentalism and sustainability in St. Louis. More than 20 of the vendors at the Trade Show offered "green" products for sale to the Park Service and other agencies. Vendors set up what was called an "ecology tent" outside the hotel to demonstrate how habitats could teach people to live more sustainably. [3]

Rocky Mountain National Park |

The two conferences occurred in different political environments. The 1988 meeting took place in a more combative political environment at the end of President Ronald Reagan's Republican administration during a period of budget decline. A week before the conference, the Wilderness Society had issued a report calling on the federal government to move all hotels and other concessions out of the national parks and listing ten parks as endangered, including Rocky Mountain and Yellowstone. In addition, the National Parks and Conservation Association had recently issued a report recommending a $50 million annual increase in the Park Service's budget just to fix a backlog of resource-management problems. A recent General Accounting Office survey had concluded that the park service had an unmet need of $1.9 billion for maintenance and capital improvements. [4]

In part reflecting the contentious nature of some issues and the level of interest in the Park Service's response to these reports, the 1988 conference received much media attention. Nearly 40 media representatives attended, to include CBS Evening News, ABC World News Tonight, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Minneapolis Star Tribune, Atlanta Constitution, and smaller papers in the West. Park Service related stories hit the front pages of newspapers across America that week. [5] Discovery 2000, by contrast, drew only limited media coverage. Conference Chair Jerry L. Rogers conceded that organizers should have done more to make the media aware of the importance of the conference. [6]

Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site |

Discovery 2000 came at the end of President William Clinton's Democratic administration during a period of modest expansion and significant change. The Service had experienced a major restructuring in the mid-1990s. Funding for the national parks had increased under the Clinton administration from $1.38 billion in 1992 to $2.04 billion in 2000. That increase was in addition to $416 million the Service had collected from admission fees since 1996. "We feel good about the things that have gone on for the Park Service in the Clinton administration," said Nat Wood, assistant director of external affairs for the Park Service. During the Clinton administration several new units had come into the national park system that reflected a growing awareness of and emphasis on cultural diversity such as Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site, Sand Creek Massacre Historic Site, and Rosie the Riveter-WWII Home Front National Historic Site. These units, said Director Stanton, honored the minorities and women who had helped shape American history and culture. [7] President Clinton had established a number of new National Monuments but had left most of them under the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. The effect that this practice would have on the Park Service and the Service's future role in relationship to these other agencies would become a subject for discussion at the conference.

Although Discovery 2000 was more focused on the more distant future than the Grand Teton conference, both addressed critical issues facing the National Park Service. The problems the Park Service faced in 1988 and 2000 were similar in many respects — to include development around park borders, invasive non-native species, air pollution, and deteriorating roads and facilities. Some particularly contentious issues were discussed in 1988 such as the reintroduction of the timber wolf in Yellowstone and the potential politicizing of the Park Service. The 1988 conference also focused on the current legislative agenda and on communications and media relations, perhaps reflecting the Park Service's desire and need to improve in this area. Conference participants also addressed the future of the National Park Service; park boundary expansion proposals; bio-diversity in the parks; the use of marketing techniques to increase park visitation; demographic changes; threats from outside park boundaries; and education. Some of these same issues were discussed in St. Louis such as the future of the Park Service, education, resource protection, the role of science, bio-diversity; leadership; demographic changes, threats from outside park boundaries, and environmentalism and sustainability.

A strong thread running through both meetings was the continued conflict between two Park Service missions: recreation and preserving resources. The conferences reflected the ongoing debate over how best to accommodate park visitors. Both emphasized the increasing threats to parks from outside their borders and the need to form partnerships with surrounding communities. They emphasized the Park Service's increasingly important role in educating the public. The addressed the growing threat of invasive, non-native biological species. At Discovery 2000, Park Service leaders indicated that the focus of the agency's mission was shifting from accommodating visitors to preservation of park resources. While the 1988 conference focused primarily on Park Service units, Discovery 2000 emphasized the threats to parks and park-like places everywhere on the planet and the need to be assertive in working with others to protect those places. The Service had launched what was known as the Natural Resource Challenge, a program to give park managers a scientific basis for decision-making. The initiative proposed to spend roughly $20 million a year over the next few years to bring science back into the parks. A companion initiative, the Cultural Resource Challenge, was announced at Discovery 2000.

The 1988 General Superintendents Conference

When Park Service Director William Penn Mott Jr. called for a conference for all park unit superintendents in early 1987, he left most of the planning and the agenda to a committee of superintendents. Mott named Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Robert Barbee as conference chairman. The planning committee included several superintendents and assistant directors to include Dan Wenk, Superintendent at Mount Rushmore National Memorial. At Barbee's request, Joan Anzelmo from Yellowstone served as conference coordinator. Organizers planned the conference with a $600,000 budget and the theme, "Planning for the 21st Century." The purpose of what would be the first general superintendents conference since 1977, was "to share and discuss ideas face to face," Mott said. The Director called the conference to boost morale, reaffirm the mission of the Park Service, provide a forum for leadership, review current issues, address the challenges of the future, and, most important, to provide inspiration. While traveling throughout the national park system, Mott had begun to realize "that we needed to collectively gather all Superintendents and senior NPS managers for a conference to look at current critical issues and go about the business of planning the future direction of the National Park System." [8] The planning committee, with Mott's approval, selected speakers who would "inspire, provoke, and stimulate." "This is not a regional or headquarters agenda," Chief of Public Affairs George Berklacy observed, "this conference is by and for superintendents." [9]

Golden Gate National Recreation Area |

The conference faced criticism from the start. In early May, Federal Times published an article questioning some of the activities associated with the conference. The article criticized the Park Service for its plans to spend an estimated $600,000 for the conference and questioned whether the benefits would outweigh the cost. "In a time of fiscal crisis, on the surface this may not seem like a good investment," conference committee member Brian O'Neill, superintendent of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, conceded in the article. But he also pointed out that the meeting was "designed to rebuild the esprit de corps of the park service" and that the Park Service had not had a similar meeting in over 10 years. The article indicated, however, that others believed it was inappropriate to hold such a meeting when many parks could not afford proper maintenance because of budget constraints. [10]

Stung by the criticism, Mott quickly released a memo reaffirming his commitment to holding the conference and his approval of the conference agenda. To keep costs down, he said, he had decided not to hold the regional superintendents conferences that fiscal year. He reiterated that the conference would be "a provocative and inspiring" meeting with nationally acclaimed resource speakers who would address broad topics concerning national parks and their future needs and challenges. [11] The cost issue was short-lived. None of the other media representatives who later wrote about the conference would question its costs. Rather, they would focus on its substance.

The four-day conference opened at Jackson Lake Lodge on Tuesday May 31, 1988. Participants included the Park Service's 341 superintendents, 10 regional directors and staff, and about 50 people from its headquarters in Washington. Six former Park Service directors attended: Russell E. Dickenson, William J. Whalen, Ronald H. Walker, Gary Everhardt, Conrad L. Worth, and George Hartzog. Other dignitaries included Wyoming's Democratic Governor Mike Sullivan; Republican Senator Malcolm Wallop from Wyoming; Republican Congressman Richard Cheney from Wyoming; Democratic Congressman Bruce Vento from Minnesota; Cy Jamison, Subcommittee on National Parks & Public Lands, and former Secretary of Interior James Watt. The president and vice-president of the National Parks and Conservation Association, Paul Pritchard and Destry Jarvis, attended as did eleven senior representatives of various concessions and recreation companies and representatives of Parks Canada.

The serene mountain setting could not mask controversies. Politicians and interest groups competed for attention from the first moments of the conference. While Wyoming's Governor Sullivan and Senator Wallop warmly praised park superintendents for their "widely respected professionalism," each made it clear they would continue to resist Park Service plans to reintroduce wolves at Yellowstone National Park. Meanwhile, Bruce Vento, an outspoken congressional advocate of the parks, promoted his controversial legislation to grant the Park Service greater autonomy. [12]

Redwood National Park |

The conference opened with a carefully planned and prepared 15-minute, 120 slide audio-visual presentation produced by the Park Service's Harpers Ferry Center in West Virginia. Though stunning and inspiring, the presentation focused almost exclusively on the natural resources in the National Park system and included few images of cultural resources. In his opening address, Director Mott called upon the assembled superintendents to promote diversity within their management ranks as well as diversity in park ecosystems. He also encouraged them to act boldly in defense of their parks. "I have often told you I want you to be risk takers. What I mean by that is to encourage you to analyze carefully each management option you consider," he explained. Mott challenged the superintendents "to stand up for park values." "We cannot expect someone else to do that for us," he said. "We must be willing to do that ourselves."

Mott went on to discuss relationships with communities outside park boundaries. The National Park System, he said, was "the storehouse of our culture's greatest treasures," but there were "some ominous cracks in the storehouse." The parks, he said, "are no longer islands" and faced numerous threats from outside park boundaries. The Director encouraged superintendents to reach out to the surrounding communities and work with government agencies and the private sector to resolve problems before they reached a crisis stage. "That," he explained, "is our challenge as we move into the 21st century."

Reflecting the new emphasis on scientific research and the importance of bio-diversity, Mott warned that the park system had "inadequate basic inventories of the resources contained within our boundaries." The Park Service, he said, must close the gap between "what we know and what we should know if we are to adequately preserve and protect the values for which the parks were established." [13] This issue would be a dominant theme years later in St. Louis.

Congressman Vento, who served as Chairman of the Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands, then addressed the conference. The outspoken Democrat asserted that Interior Secretary Donald Hodel, Assistant Secretary of Interior for Fish, Wildlife and Parks William P. Horn, and the Reagan administration had muzzled Park Service professionals and starved the Service of funds. They had continued to pursue the program of developing public lands (basically for energy and recreation) launched by former Interior Secretary James Watt. National parks, he insisted, "are the crown jewels of our natural heritage and those people are turning them into rhinestones." [14]

Vento charged that the parks were "in a state of rapid decline" because of political interference, dwindling budgets, and the Reagan administration's insistence that development should take precedence over preservation. Declining support from the Reagan administration had meant less money for maintenance and staffing when the parks were drawing record crowds. Most of the budget cuts, he added, came from "political appointees" who were unwilling to serve as advocates for preservation of America's cultural and natural heritage. He called political interference "a cancer that's working its way through the national park system." [15]

The Congressman advocated a reorganization of the Park Service. Under his proposed legislation, the Park Service Director would be appointed for a five-year term, longer than the term of the president who appointed him. In addition the bill would create a three-member park system review board which would report to the president and Congress annually, recommending improvements for the park system. These changes, Vento said, would free the Director from political pressure. Vento also called for a vigorous program to acquire privately owned lands within park boundaries and for strong park action to minimize park degradation from threats outside park boundaries. "Air pollution, development, water projects, overuse, and a host of other problems affecting the resources of the parks demand that Congress address the issue of park protection, and we will," he said. [16]

Vento claimed that the park system budget under the Reagan administration, when measured in real dollars and adjusted for inflation, had declined by $275 million from 1980 to 1989. "The problem for the National Park Service is the need for strong advocacy," he said, and the Service was not getting it from its Interior Department superiors. In a news conference later that day, he charged that in many instances Director Mott had "had the rug pulled out from under him" by senior Interior officials. [17]

The next speaker, William P. Horn, presented a very different perspective. Horn denied there was widespread disharmony in the Park Service because of political interference. He preferred to call it an atmosphere of "creative tension." Horn objected to what he called "a continuing drumbeat of criticism that the administration is anti-park." "It's a bum rap," he said. Horn added that funding for national parks had grown from $391 million in 1980, the last year of President Jimmy Carter's administration, to $734 million in FY 1989, "the largest budget ever for the National Park Service." The budget, he insisted, represented a 29 percent post-inflation real growth in the agency's budget, and outstripped the 23 percent increase in visitation over the same period. Park Service employment had increased from 15,576 full time employees in 1982 to 16,461 in 1989. These numbers, he said, "are at odds with the pernicious mythology that we are not supporting the national park system." Horn defended the Reagan administration's record on parks and later told reporters that he opposed the Vento bill. Rather, he favored a healthy mix of senior political management with senior career management. [18]

Grand Canyon National Park |

Mott vehemently denied Vento's claim that the Park Service was "hobbled" by politics. "No one, not even the secretary of Interior Donald Hodel, has ever throttled me in saying what I personally want to say," Mott said. [19] At a somewhat tense unscheduled news conference later that day, managers of the dozen most embattled parks rallied around Mott in defense of the Reagan administration's record. They explained to reporters how resource management had improved during the 12 years since the last general superintendents' conference. They pointed to upgrades such as demolition of two dams in Rocky Mountain National Park, removal of wild burros at Grand Canyon to allow bighorn sheep to rebound, and signs of increasing numbers of grizzlies at Yellowstone. "Biologically, we're in better shape than seventy-five years ago," said Barbee. Barbee and other superintendents acknowledged that they had had policy disputes with Reagan appointees but insisted that allegations of environmental groups were often exaggerated. [20]

The National Parks and Conservation Association joined the fray, charging that Secretary Hodel had proposed fundamental changes in park policy "over the strenuous objections of park professionals." Those changes, according to the association, gave preference to visitors' recreation over preserving resources. Association vice president Jarvis accused the Reagan administration of "trying to change the philosophy of the national parks to favor recreation over preservation." The debate over how far the Park Service should go to accommodate visitors continued throughout the week. Mott and several superintendents countered that preservation remained foremost in the latest draft of the park policies manual. [21]

Thursday morning was devoted to the management of natural and cultural resources. The afternoon and evening were set aside for whitewater rafting, hiking, horseback riding, and sightseeing, followed by a western barbecue with a bluegrass band.

The keynote speaker for Thursday, Dr. Robin Winks, Professor of History at Yale University and Past Chairman of the National Park System Advisory Board addressed the themes of education and changing demographics. He told the conference, "I take the national park service of any society as a series of symbols about what a people chose to take pride in. These are the testimonials, the building blocks that Americans believe they have done historically. You begin to get to the heart of a people by viewing what they have chosen to preserve." Winks told the superintendents that they were stewards over what he viewed as "the single greatest university of the world." "Any national park system is a political expression as well as a cultural expression," he continued. "The natural resource is not for recreation. You are conserving the great natural and historical heritage of society and the wildlife thereof." "There need to be recreation areas. These are subjects of great pride and while recreation will occur in them, let's not forget why we created them … You should think of those visitors as coming for an education." Winks' expression "a university without walls" would resonate long after the conference.

Winks cited several obstacles the Park Service faced in "educating" the public about the parks and the American heritage that the parks represented. The chief one, he said, was ignorance about the parks, and another challenge was demography. Given the current ethnic trends in the U.S., Winks said, within 20 to 30 years "a majority of the people visiting Concord battlefield will say, 'This is not my revolution,' or visiting Manassas battlefield, 'This was not my Civil War.'" The Park Service had to educate these new Americans about the cultural heritage represented by the national parks. It must "fight against any fragmentation," Winks added, and must think of all its resources together. [22]

The next speaker, Dr. Joseph Sax, an environmental law expert from the University of California at Berkeley, focused on threats from outside park boundaries. Sax accused the Park Service of being "too timid" about protecting its lands from encroaching development. Superintendents, he said, were expected — and sometimes required by law -- to sue developers, loggers, oil drillers, or others whose activities threatened the parks. "Superintendents have the blessings of Congress to file the lawsuits," he added. And if they did not, they could be sued themselves for not doing so.

Sax also told the superintendents that they had a powerful weapon, granted by Congress, to deal with developments on private property outside park boundaries. That method, he said, was litigation. Congress encouraged the park superintendents — through the interior secretary — to bring lawsuits against those external developments that threatened the parks. Such legal action would allow for a resolution of the problems without a precedent-setting federal zoning law, because each case would be settled based on its individual facts and merits. The language of the 1916 legislation creating the National Park Service would strengthen any lawsuit.

Congress recognized the growing insignificance of boundaries, Sax said, and the loss of private and public distinctions in the encroachments on the national parks. "It was intended that the use of the courts would be made," Sax added. Some activities occurring near parks were not illegal under local law, he said, such as visual intrusions and subdivisions. But the organic act of 1916 established "a federal standard of protection, not an adoption of state and local standards." Consequently, the Park Service could expect to be successful in lawsuits protecting resources threatened from outside park boundaries because of the special and "absolute, not to be compromised" protection offered national parks. [23]

The superintendents gave Sax a polite round of applause but were reluctant to follow his advice. Privately many expressed doubts that taking matters to court was the best response. Several superintendents indicated that they had reservations about using the courts to resolve border disputes. They preferred using public education first. Some indicated that they had not filed suit in any of the conflicts with private development around their parks. They preferred to negotiate with developers, lumber, mining, and other interests. [24]

The next speaker, Dr. Valerius Geist, a zoologist and professor of environmental design at the University of Calgary, addressed the threat of non-native species and the importance of bio-diversity. Geist warned the superintendents that commercial production of wildlife for consumers would result in the importation of heartier Eurasian domestic strains of wildlife which would out-compete native species in their own habitats. Already, he said, the United States had tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of non-native species in the wild. Geist predicted that the importation of non-native game "to satisfy gastronomes' palates" would almost certainly result in the destruction of native North American wildlife. Releases of animals from game farms were inevitable, he said, and American native species could not compete against heartier Eurasian species. "There are 30 million wild animals in the United States," he said. "For every game animal, there are five firearms, nine human beings and 110 head of livestock. The odds of survival depend entirely on the sympathetic view of the people." Part of the solution, he concluded, was to remove control of exotics from private hands. [25]

Friday was dominated by sessions on marketing and urban parks. Marketing experts urged park managers to use everything from television ads to additional highway signs to encourage park visitation. Superintendents were told they must forge a marketing strategy to meet the needs of the changing population. Speakers included representatives from some of the nation's leading marketing firms to include Patricia Russell-McCloud, President of Russell-McCloud and Associates and Ann Clurman, senior vice president of a New York marketing consulting company called Yankelovich, Clancy, and Shulman.

Statue of Liberty National Monument |

Clurman observed that new surveys by her firm indicated that Americans were starting to feel "overwhelmed" by technology and were becoming more nostalgic. "They are wanting to know more about their past," she said. "And that probably means even more visitors to national parks." Parents, she said, would be dragging their kids to the same places their parents took them such as the Statue of Liberty and the Washington Monument. But most of the park service's 340-plus units were relatively unknown to the public. Americans, Clurman continued, shared "a profound need to reconnect." Several growing trends, the maturing of the baby-boom generation, a growing dissatisfaction with the '80s style materialism and concern for the environment, suggested even greater popularity for the nation's parks. That mindset, she said, would define an American generation that was better educated, more discriminating, lived longer and had more disposable income and leisure time. [26]

Echoing some of the same themes, Dr. Alan Hogenauer, president of Checklist, a New York marketing consultant company, told the conference that the public's awareness of their national parks, he said, was "deplorable." He stressed that marketing should not mean "the blind pursuit of hordes of new visitors." Nor should it include "abrasive TV ads" or anything tasteless or inappropriate. "The word marketing offends many people in this agency," he conceded. "But park professionals must see beyond that prejudice to understand that they can no longer "sit and wait passively for the visitor."

Another speaker, Dr. John Crompton, Professor of Parks and Recreation at Texas A&M University told the superintendents that instead of pursuing the same marketing goal as private industry — sales — they should try to make parks more satisfying to visitor. This included distribution of people in the parks so they do not try to visit the same scenic view at same time. Also, the Park Service should pursue the "right visitor" instead of visitors in general. "Many people come to national parks and they have no idea what they're about, " he said. The Park Service needed to inform people why the park is there in the first place — that the parks are there to make them aware of their cultural and natural heritage. [27]

Saturday included sessions on interpretation, media relations, and a closing banquet with Dick Jackman, the Director of Corporate Communications for Sun Company, Inc., as the guest speaker. Dr. John Hunt from the University of Massachusetts discussed domestic and international tourism trends and their impacts on the National Park Service. Robert Dilenschneider, head of the world's largest public relations firm, Hill and Knowlton, Inc. talked about crisis management. He warned superintendents that the major environmental crisis of the 1990s would strike the national parks, and as "guardians of America's soul" they must be adept at handling the conflicts. He warned that they would find themselves "in the middle of swirling change." Superintendents would confront acid rain, genetic engineering, waste management and the changing strategies of environmental activists, the five issues that will dominate the 1990s, he said. "You are going to be in the center. For the various interest groups, you're going to be in the position of the pawn on the chessboard. You've got to get yourself out of that position." The ability to work with media was critical to crisis management, he added. Dilenschneider warned Park Service officials that they were unprepared because they often were poorly trained in administrative matters and had no overall long-range strategy. He predicted the increased use of computers throughout the Service. [28]

After a non-denominational worship service on Sunday, the participants left Grand Teton National Park having reaffirmed some basic conservation principles that had shaped the Service since its creation in 1916. One reporter predicted that the conference would spark an intensified commitment to lowering the historic barriers between parks and neighboring communities. More than once, Mott exhorted his superintendents to go beyond the boundaries of our parks and resolve problems before they reach a crisis stage. [29]

Mesa Verde National Park |

Conference organizers rated the meeting as a success. Comments from participants were positive. The facility worked well, the speakers were engaging and provocative, and participants had ample opportunity to interact. The morale boost that Mott had hoped for seems to have occurred. Chrysandra Walter, superintendent of Lowell National Historical Park observed, "We have renewed our sense of purpose." "This week has been almost like a religious retreat, said Bob Heyder, superintendent at Mesa Verde National Park. "I'm going away refreshed and inspired." [30] The conference also encouraged participants to think more seriously about the future and changing demographics in the country and how to better communicate with the public and the news media.

Yet, participants left with no clearly articulated plan or agenda to guide them in the next century. The focus seemed to be more on dealing with contemporary issues than developing any significant plans for the future. In the summer of 1988, the Park Service faced not only a possible change in administration but also growing threats to park resources. Throughout the week participants received warnings and lessons in politics and power, psychology and salesmanship, one reporter observed, "skills shaped less for wilderness than for a civilized world of every more people and ever more pressure." A common solution was offered to superintendents dealing with growing number of friends and foes of the parks — Marketing. Marketing in this instance was not a search for greater numbers of visitors but the presentation of an image. [31]

A number of contentious issues were aired during the meeting and many perspectives joined the debate. The views of Mott, Vento, Horn, National Park and Conservation Association leaders Pritchard and Jarvis, and experts from outside the Park Service were all heard. Participants discussed the future of the Park Service, reactions to proposed legislation to change the method of selecting the agency's Director, restoration of the timber wolf to Yellowstone, and boundary expansion proposals by the National Park and Conservation Association.

The divisions between conservationists and administration officials were not resolved. They could not even agree on how much money was being allocated to the Park Service. Congressman Vento described a shrinking budget, while Horn claimed there was a 29 percent increase. Career officials said President Reagan had in fact increased money available for day-to-day expenditures but the administration had all but eliminated programs to protect natural resources and acquire additional park land. One reporter indicated that when inflation is considered, the budget had been cut between 10 to 30 percent. Superintendents agreed that environmental threats to parks from beyond their borders remained the most difficult to reconcile. [32]

The conference gave added visibility to the issue of returning the timber wolf to Yellowstone and helped propel it in the political arena. But at one point, the issue briefly took on a light note. At the closing banquet Mott provided attendees with buttons containing a wolf's head with blinking eyes. Around it were the words "Bring back the Wolf. The 'Eyes' Have It." As Mott approached the podium to address the conference's closing banquet, suddenly the lights went out. Then from small, battery-powered wolf-head buttons pinned to almost every person in the audience, tiny, red wolves' eyes began to blink on and off in the darkness. As if on cue out came a long, drawn out "OOOOOOO!" some 500 voices imitating a wolf howl. The legend on each pin read "Bring Back the Wolf. The 'Eyes' Have It." Participants laughed and applauded. Some months earlier Mott had had the pin designed and produced as part of the public education campaign about the wolf. With equal good humor, Senator Wallop, who resisted returning the wolf to the Yellowstone ecosystem, countered with his own button. It read, "SOS. Save Our Sheep. The 'Ewes' Have It." [33]

Measuring the impact of the conference is difficult, particularly since no new reports or policy initiatives grew out of the meeting. As participants returned home, what would soon become a devastating wildland fire episode in Yellowstone National Park was just beginning. Barbee and Anzelmo had planned to make the papers available in some form but could not follow up on the conference as they had planned. The fires would consume much of their time and energy over the next two years and become a major political focus for the agency. [34]

The Grand Teton conference did not resolve any of the major problems facing the Park Service, but in some ways it marked the beginning of a decade of change. In October 1991, the Park Service held a 75th Anniversary Symposium called "Our National Parks Challenges and Strategies for the 21st Century" in Vail, Colorado. The mission of the conference was to review the problems and challenges confronting the Park Service, discuss issues and options, propose strategies, and make recommendations. "From the start I wanted it made clear that this was not to be a white-wash of past practices by the Park Service," Park Service Director James M. Ridenour explained. "I wanted the agenda to be wide open and I wanted help from the private and academic world for this introspection." [35]

Unlike the Grand Teton meeting, which had been planned and organized by senior Park Service officials, Vail was convened under the direction of Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government, the World Wildlife Fund, The Conservation Foundation, the National Park Foundation, and the National Park Service. It brought together nearly 700 experts and interested parties from inside and outside the Park Service to consider the future of the National Park System. While the vast majority of 1988 conference participants were Park Service employees, nearly half the Vail participants were from outside organizations and institutions. This reflected the growing recognition that the Service did not function in a political or institutional vacuum.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore |

The conference was guided by a steering committee chaired by William J. Briggle, a veteran Park Service employee, with Henry L. Diamond, of Beveridge and Diamond, P.C, a highly respected conservationist, as symposium general chair. In addition to Park Service members, the steering committee included representatives from The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, Coopers and Lybrand, and John F. Kennedy School of Government, former ambassador to Australia William Lane, and President of the National Park Foundation Alan Rubin. Its task was to prepare a comprehensive report and set of recommendations for improved Park System stewardship and Park Service management for the Director of the Park Service.

In the spring of 1991, the steering committee formed working groups focused on organizational renewal, resource stewardship, park use and enjoyment, and environmental leadership. Each working group consisted of non-Park Service chair and vice chair, three Park Service managers, and five members from outside the Service. Unlike the 1988 conference, which was dominated by superintendents, the Park Service members represented various park units and programs and a broad range of professional experience and expertise. Interested individuals from within and outside the agency provided written and oral comments to the working groups. Congressional representatives and their staff members also provided their perspectives. The groups held extended working sessions to formulate preliminary recommendations. Out of these sessions, they produced draft reports, which served as the basis for discussion at the meeting in Vail. Conference participants joined in dozens of discussion sessions and revised the preliminary recommendations. They also attended plenary sessions where distinguished leaders from within and outside the Park Service presented their views on national and international park system issues. The conference addressed the issues of environmental leadership, organizational renewal, park use and enjoyment, and resource stewardship.

The steering committee later produced a final report called "National Parks for the 21st Century: The Vail Agenda, Report and Recommendations to the Director of the National Park Service." The report contained six strategic objectives that together constituted the Park Service's vision for the 21st century (Resource Stewardship and Protection; Education and Interpretation; Proactive Leadership; Science and Research, and Professionalism) and more than 140 specific recommendations for achieving them. Echoing some of the themes from the 1988 meeting, the report highlighted threats to park resources from inside and outside park borders and the need to "ensure continuity and sustainability in the public's access to park values." [36]It reflected the inherent tension in providing access while properly managing resources. The report encouraged the Park Service to convey the meaning of each unit and its contributions to the nation's values, character, and experience through education and interpretation. On the issue of leadership, the report observed, "The National Park Service has lost its ability to exercise leadership in determining the fate of the resources and programs it manages." [37] In the area of science and research, the report noted that the Park Service was "extraordinarily deficient" in its capacity "to acquire, synthesize, act upon, and articulate to the public sound research and scientific information." It recommended that the agency engage in a sustained, integrated program of natural, cultural, and social science resource management and research to acquire the information that it needed to manage and protect park resources. The report called on the Service to create and maintain a highly professional organization and work force with higher standards and better training. [38]

Held just three years after the superintendents meeting, the Vail conference reflected some of the fundamental changes occurring within the Park Service. With its mix of working and plenary sessions, emphasis on partnerships, broad participation, and candid discussion of critical issues, it helped set the stage for Discovery 2000.

George Rogers Clark National Historical Park

DISCOVERY 2000

In September 1998 at a meeting in Grand Teton National Park, Park Service Director Robert Stanton told his senior officials that there would be a general superintendents conference in 2000. During the next few weeks, the Director began describing the conference as a "general conference" rather than a "general superintendents conference" because he recognized that the mission of the Park Service included broader responsibilities than managing the National Park System. Stanton appointed long-time Park Service executive Jerry L. Rogers as chair of the conference team, with Superintendent of Independence National Historic Park Martha Aikens, Superintendent of Mount Rushmore National Memorial Dan Wenk, and Superintendent of Pinnacles National Monument Gary Candelaria as co-chairs. The conference team held the first of many planning meetings on April 29, 1999 after observing an innovative, discussion oriented Intermountain Regional Superintendents Conference. Stanton also appointed Intermountain Regional Director John Cook, Alaska Regional Director Bob Barbee, and Deputy Director Jackie Lowey to a steering committee to represent the National Leadership Council in overseeing the conference team's planning effort. Having the steering committee enabled the conference team to make decisions quickly without action from the larger National Leadership Council.

Stanton specified that the conference take place in 2000 in St. Louis if the team could arrange a suitable meeting place. He made it clear to planners that he wanted the conference to take advantage of unique moment in time — the millenium — to focus on the distant future. Thus, the steering committee and conference team emphasized "vision" rather than "planning." Stanton designated the highly experienced Jim Gasser as meeting planner. The conference team, the steering committee, Deputy Director Denis Galvin, Midwest Regional Director Bill Schenk, Office of Policy Chief Loran Fraser, Harpers Ferry Center Manager Gary Cummins, and Jefferson National Expansion Memorial Superintendent Gary Easton met in St. Louis in June 1999 to lay out the basic goals and framework that would guide their planning. They agreed that the 2000 conference would be visionary; include a substantial percentage of "partners;" encompass the broader mission of the Park Service beyond park boundaries; encourage active participation; include a mix of plenary sessions and small discussion sessions; and focus on resources, education, and leadership. [39]

Conference planners anticipated a much larger audience than was present at Jackson Lake Lodge and knew that it would be difficult to accommodate such a large number in any national park in September. They also recognized that the public might resent the Park Service taking up all the accommodations in a National Park -- a major vacation destination -- for its own use. St. Louis' central location allowed easy access and kept travel costs down. Moreover, the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and the Gateway Arch were symbols of optimism and possibilities for the future — an appropriate inspiration for a conference about vision for the 21st century.

In December 1999 Director Stanton publicly announced his plan to convene in September of 2000 the first Service-wide conference since 1988, which would be called "Discovery 2000: the National Park Service General Conference." Stanton laid out three goals for the conference: to develop a vision of the Park Service's role in the life of the nation in the 21st century; to inspire and invigorate the Service, its partners, and the public about this vision, and to develop new leadership to meet the challenges of the future. "The intent," he said, "is to produce thinking that will guide us for several decades beyond our gateway of discovery here in St. Louis, Missouri."

The conference would explore four tracks or themes: cultural resource stewardship, natural resource stewardship, education, and leadership. Aikens would lead a leadership track; and Candelaria, now superintendent of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, would lead the natural resources and cultural resources stewardship tracks with the assistance of associate directors Kate Stevenson and Michael Soukup. [40]

The conference team recruited nationally and internationally renowned speakers to highlight each of the four tracks. They first enlisted organizational leadership expert Dr. Peter Senge (leadership), followed by two-time Pulitzer-Prize winning Harvard biologist Dr. Edward O. Wilson and accomplished St. Louis scientist Dr. Peter Raven (natural resources), historian Dr. John Hope Franklin (cultural resources), and best-selling author and poet Maya Angelou (education). All but one of these distinguished individuals donated their time and expertise — a donation of services estimated at $150,000 or more. Their keynote addresses would be followed by a broad series of lectures, workshops, and in depth discussions.

The five-day conference opened on September 11, 2000 at the Regal Riverfront Hotel in downtown St. Louis with more than 1200 participants. It included Park Service members from the Washington office, the regional offices, and the parks, as well as their partners. It also drew representatives from non-profit and advocacy groups, often some of Park Service's harshest critics. Former directors Roger Kennedy, Walker, Whalen, Dickenson, and James Ridenhouer participated in the conference. George Hartzog who was unable to attend addressed the participants by videotape. In contrast to the Grand Teton conference, only one congressional representative attended — Mark Souder from Indiana. Nor did the conference attract the same level of media representation as at Grand Teton National Park. Planners invited Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt to attend, but he declined.

Much like the 1988 conference, the conference opened with a dramatic, fast-paced video produced by Harpers Ferry Center called "A Mosaic of Ourselves." Unlike the Grand Teton presentation, "A Mosaic of Ourselves" included many images of Park Service cultural resources and examples of National Historic or Natural Landmarks, National Register properties, and other mission-related properties outside the National Park system. Former Director Hartzog addressed the conference by videotape. Conference Chair Jerry Rogers told the participants that their job was "not to plan the future but to conceive it." He challenged them to look ahead ten to thirty years and develop a vision for the next century. [41]

Director Stanton developed the theme of a week of work and vision in his opening address. "We are here to contemplate a vision — to dream, anticipate, and begin to formulate the role the National Park Service will play in the future of this nation," he said. He went on to declare that Discovery 2000, the National Park Service general conference was "a gathering of friends. It is safe here to think aloud." The national parks, Stanton said, could no longer be viewed as "islands of nature, free from the pressures of growth and development." He explained, "Today we know that parks can and must be created in which many jurisdictions and many partners and owners are involved."

The Director then focused on natural resources, expressing concern about dying species and disappearing ecosystems. He also emphasized the importance of historic places, calling America's history "a patchwork quilt in which each piece has a special story but the full effect is only achieved when they are sewn together." "The preservation of our cultural resources," he said, "demonstrates the values of diversity and community that honor and link us with the heritage of our predecessor and represent our individual and collective legacy to our successors and future generations."

The Park Service's mission, Stanton observed, had extended far beyond the parks themselves. The world had changed. That is why Discovery 2000 was, he explained "more than a superintendents' conference the broader concept of a general conference is the reason why servicewide, regional, and local managers of programs, as well as many delegates-at-large are here along with the superintendents."

The demographics of America was shifting, Stanton said, but the culture and values of this changing America were not yet woven into the National Park theme. Minority communities were still underrepresented. The changed world was why the conference planners had included many non-Park Service employees in the audience — people from other federal agencies, state, local governments and tribes, universities, foundations, and elsewhere. Physical isolation no longer existed, he said, but the Park Service had to overcome other forms of isolation.

The Director noted that the eve of the millenium was the perfect time to work on vision. Beyond any plan or action, there must be a vision. He encouraged participants to participate actively in sessions, to share their vision in the "time capsule", to revisit the Discovery 2000 web site, to journal, and to "share ownership of our collective future." Finally, he emphasized the need for follow-through after the conference. [42]

The first day of the conference focused on the theme of cultural resource stewardship. Dr. John Hope Franklin, a renowned historian and scholar who served as chair of the National Park System Advisory Board, gave the keynote address. In his remarks, Franklin reflected on past changes and future challenges for the Park Service. The agency, he noted, was both an educational and cultural institution. Franklin emphasized the important role parks played as places where visitors could hear about important, complex subjects such as the struggle for racial justice, women's rights and the rights of workers. He commended the Park Service for its increasing candor in interpreting its historic sites and for its role in expanding the number of sites that related to all citizens. The Park Service, he said, had a unique opportunity to teach "in real places about real history and real nature with real things."

Looking ahead to the challenges of the next century, Franklin encouraged the Park Service to redefine its focus on the purposes and prospects of the service and the system; better manage places and programs in partnership with all levels of government and with private industry; respond to and reflect the nation's changing diverse population and demographics in both its workforce and outlook; and rededicate itself to its role as an educational institution that brings more scholars into the parks and allows more park employees opportunity to expand their scholarship. Franklin called on the Park Service and its partners to "broaden the truths we teach" in order to deepen the respect of our fellow citizens in order to deepen their support for the Service and its mission. Park Service employees, he insisted, must communicate their message outside the parks. [43]

After Franklin there were concurrent sessions on such topics as "Investing in Wisdom," "Just the Facts Ma'am: Why is Context so Controversial?", "Natural/Cultural — Nature/Human History: Is It All One?", and in a session called "How We Learn From Experience," participants discussed the importance of embracing change.

Tuesday was devoted to natural resource stewardship. In introducing the first natural resource keynote speaker, former Director Roger Kennedy observed that the Park Service must educate the public about resource protection. It must merit trust and build constituencies outside the parks. "Resource protection has to walk out of the park in the hearts of the visitors," he said. Echoing the themes Geist had presented years earlier in Grand Teton National Park, the day's speakers emphasized the important role of science and the importance of bio-diversity.

Harvard Professor Dr. Edward O. Wilson, who was regarded internationally as the preeminent biological theorist of the late 20th century and as one of great naturalists in American history, gave the "natural resource" keynote address. Wilson warned that it was a crucial time for the Park Service and for the environment in general. National parks were destined to play an even larger role. The planet, he warned, could easily lose a quarter of its plant and animal species in the next 30 years, and the national parks would become increasingly important for scientific research, education "and the future of society." Wilson observed that the parks were "our treasure house of the remnant natural ecosystems" and as such need to be thoroughly understood. The Park Service and the national parks, he predicted, would have a major role in research in collaboration with academic community. He advocated increased education to compliment the research efforts. He concluded, "There's no better classroom than our national parks, and no more respected teachers" than the people of the National Park Service. [44]

Concurrent Sessions that day included such forward-looking topics as: "The National Park Model: Vestige of the Past — Or Foundation for the 21st Century?," "Direct Dealings: Working with Park Neighbors of the Future," "Science-based Decision-Making: How Much Information is Enough?" In one session, "Natural Resources: Winning in the Parks, in the Courts, and for the Public," Superintendent Mike Finley urged the crowd to "adopt an attitude of rigid defense," much as Sax had in 1988. Finley and Solicitor Dave Watts emphasized the importance of fact gathering and the need to be prepared for lawsuits. In a lively discussion, session participants questioned whether there were opportunities in waiting to be sued or seeking lawsuits when park resources were in jeopardy. Watts advised the participants to fund data gathering, keep an eye on new policies, and engage in long-term legal planning now.

In the closing plenary session that day, Dr. Peter Raven, addressed the conference. Raven, a nationally and internationally renowned conservationist, held the position of Engelmann Professor of Botany at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri and served as Director of the Missouri Botanical Garden. Raven urged the Park Service to make the national parks accessible and meaningful to every segment of U.S. population. The Service, he said, could not manage resources in parks without a well-resourced scientific staff on site. It should adopt a goal of managing parks for the greatest amount of bio-diversity possible and should pay special attention to invasive species. He also recommended increased coordination with other land management agencies and the private sector. The Park Service and the Interior Department, he added, must invest further in understanding global climate change and other forms of pollution coming from outside parks. Raven argued that the parks would have their greatest value in the educational arena. After his formal remarks, Raven and Wilson responded to questions from conference participants and a lively discussion ensued. In one particularly powerful moment, Wilson observed, "The national parks will be very vital for the long-term psychological health of the human species." [45]

Wednesday focused on the theme of education. Former Director Dickenson introduced gifted poet, dramatist, and author Maya Angelou. He emphasized that education programs and interpretation were "key to a quality park experience" and called for improvement in the interpretive program. Keynote speaker Angelou praised, encouraged, and challenged conference attendees, using poetry, humor and song. While sharing deeply personal stories about her own life, she encouraged Park Service members to read and write poetry to use poetry and the dramatic arts interpreting the parks, American history, and the natural sciences. With observations such as "I am human, nothing can be alien to me" she established a profound emotional connection with the audience. [46]

Concurrent sessions that day included "Silent Garden: Broaden the Stories — Build Constituencies," "Long-Distance Learning and Technology: Reaching Those Who Don't Visit Us," "Key Education Trends in the Near Future," "Reaping the Sweet Rewards: Building Sustainable Education Programs." One participant observed that the Park Service needed to go to the public with its education efforts rather than wait for the public to come to it. Another envisioned a future in which parks provided life-changing experiences for all young visitors.

Thursday was devoted to the subject of leadership. Dr. Peter Senge, a nationally acclaimed expert and lecturer on organizational leadership, opened the sessions. Senge told Park Service members that they had the opportunity to put more meaning into people's lives at a time when many sensed that something was "deeply out of whack." People were desperate for quiet time and a place where they could reconnect with what is primary. Senge described the gap between one's vision and the current reality in which one lived as "creative tension." He challenged the commonly accepted definitions of "leadership," which often mean dominance and control. Leadership, he concluded, had nothing to do with position or title. It was the capacity of the human community to shape its future. It was both deeply personal and inherently collective. He defined leadership as one who helped workers believe they could shape their own futures. [47]

More than three dozen workshops on leadership followed to include: "Will the NPS Ever be Able to Add Two Plus Two and Arrive at Four," which focused on how the NPS implemented and accounted for its programs and policies, "Park Development and Future Park Preservation: Alternative Transportation Planning and Gateway Communities," "From Crisis-of-the-Moment to Visionary Thinking: Making the Transition," and "Leadership Beyond Park Boundaries." One session examined the possibility of using national parks as venues for conferences in which corporate leaders would discuss the adoption of sustainable practices in their organizations. Another highlighted some of the impediments to visionary thinking inherent in the Park Service. At the end of the day, all the participants once again in the hotel ballroom to hear James Lee Witt Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency discussed leadership and change. "How we treat each other inside our organizations," he said, "is one form of customer service."

Friday, the final day, Deputy Secretary of Interior David Hayes addressed the conference and Director Stanton followed with his closing remarks. Stanton told participants that they were "poised on the edge of a future in the shadow of the timeless arch of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial." The end of the conference was just a beginning for the 21st century National Park Service. Stanton noted that although Discovery 2000 had met its goal of being "forward-looking and visionary," participants needed to focus on what remained to be done and the direction the Park Service must go. "We have a monumental obligation to the future," he added, a duty to point the way in the new millenium. "We must extract from this conference and the things that follow it a clear, coherent vision that can be stated with understandable simplicity, and that will have a reasonable consensus behind it," he continued. He encouraged the attendees to "go forth" with new insights and energy, with the determination to share what they had gained and with more inclusive cultural values. Again, he emphasized the importance of diversity in the workplace.

Stanton anticipated that Discovery 2000 would lead to explicit vision statements that could be helpful to future Directors. He anticipated there would be other follow-up activities and that the work of the conference would continue. The Director then articulated his far-reaching vision for the National Park Service. His vision included an agency where each employee was valued and encouraged to reach his or her full potential. He envisioned the Park Service as an agency that exercised leadership, erased barriers with other federal agencies, tribes, state and local governments, and the private sector, and played an increasing role in education. He encouraged the agency to go beyond its preservation role to create memorable experiences for visitors. In closing, he challenged participants to incorporate the insights that they had gained during the week into their day-to-day work. [48]

In the weeks following the conference, Jerry Rogers received overwhelmingly positive feedback from the participants. Conference planners had developed 15 "measures of success" and used them as benchmarks in selecting the numerous workshops, discussion sessions, and the keynote speakers. Rogers believed he and the other committee members had come very close to achieving their goals for the meeting. They had, Rogers said, tried to the greatest extent possible to make Discovery 2000 "a dialogue-based and participatory conference, in which NPS employees of all levels and partners and critics were all equal." They had sought openness to various points of view. Rogers conceded that they had not achieved perfection in this, but they had accomplished much and learned much about planning and executing participatory conferences.

Rogers sent out messages over the next few months challenging participants to reflect not only on what they had heard the conference but also on their own visions for the Park Service. "We hoped before–and especially now–that Discovery 2000 was not an event but a beginning. Ideas, thoughts, contacts, habits (such as reflecting, journaling, writing poetry), and methods of treating subjects that began there all need to be continued, cultivated, and perfected. … This, for me, is part of the vision from Discovery 2000." [49]

Notes were taken in each workshop and discussion session so that there would be a good record. The plan was to make these notes plus journal offerings and time capsule entries available to the National Park Service's Advisory Board for use in its ongoing scholarly review of the Park Service's future. There were plans for follow-up sessions and conferences.

Lincoln Home National Historic Site

CONCLUSION

Although many participants have indicated that they found Discovery 2000 meaningful and thought-provoking, it is far too soon to assess the meeting's full impact. Questions remain: Will the optimism and energy from the conference be maintained? Will the participants continue to develop their visions for their own work and for the Park Service as a whole? Will they take the necessary actions to ensure that the "seeds" planted in St. Louis continue to grow? Will the visions lead to meaningful change in the Park Service?

Unlike the Vail conference, which produced the "Vail Agenda," neither the 1988 conference nor Discovery 2000 produced a clearly articulated plan or agenda for the 21st century. But that was never the purpose of either conference. They were not designed to provide Park Service leaders with a series of detailed resolutions. The 1988 conference was primarily focused on providing inspiration and boosting morale, while Discovery 2000 went beyond this to focus on shaping the agency's vision and purpose.

Although the two meetings differed in size, format, and focus, and reflected different political environments, they conveyed similar themes. Again and again, the discussions and presentations at these conferences reflected the fundamental dilemma that has faced the National Park Service since its inception: how to protect park resources while accommodating the needs of park visitors. Both conferences were significant, noted Joan Anzelmo, because "they gathered the core organization together with its partners, and challenged the participants to stand up for the mission, to be relevant to society and to expand in meaningful ways the diversity of the workforce to reflect the nation." [50]

Discovery 2000 was unique. It was more balanced and inclusive and perhaps stimulated more creative thought than any previous Park Service conference. While Discovery 2000 encouraged open discussion, except for the early exchange between Congressman Vento and Assistant Secretary Horn, the format of the Grand Teton conference left little room for contending viewpoints. Discovery 2000 gave equal weight to natural resources, cultural resources, and education and devoted much more attention to interpretation than the Grand Teton conference.

The emphasis on cultural resources, interpretation, and education in Vail and in St. Louis reflected fundamental changes in the Park Service. The cultural resource-related professions were growing in prominence. Discovery 2000 dramatically illustrated that a larger and more diverse group of Park Service employees had a voice by 2000. It incorporated more of the Park Service's partners and critics and reflected the agency's growing emphasis on its emerging leadership role. Together the conferences provide a measure of just how much the National Park Service changed in the last decade of the 20th century. They also highlight the significant challenges that the National Park Service will face in the 21st century, though it is too soon to know just how well they prepared the Service to address those challenges.

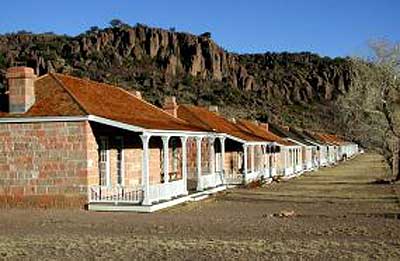

Fort Davis National Historic Site

NOTES

Unless otherwise noted, copies of all records cited here are in the files of the National Register, History, and Education Branch Division (NRHE), National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

1 Electronic message, Jerry L. Rogers to author, December 1, 2000.

2 Jerry L. Rogers review comments, January 10, 2001.

3 NPS Newsletter, Discovery 2000, No. 2, September 12, 2000, p.1.

4 "Forum targets future of national parks," Rocky Mountain News, Denver, Colorado, June 1, 1988.

5 See file of Grand Teton Conference news clippings at NRHE. Original file is in the Historical Collection at Harpers Ferry Center.

6 Rogers review comments.

7 "Park Service is shifting the focus of its mission to preservation," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 4, 2000.

8 Mary Ellen Butler, Prophet of the Parks: The Story of William Penn Mott, Jr., (Ashburn, VA: The National Recreation and Park Association, 1999), p. 208; memo, National Park Service Director to Directorate and Field Directorate, April 1988; "Mott sees conference as morale booster," Daily Sentinel, Grand Junction, Co., June 4, 1988.

9 Electronic message, Robert Barbee to author, December 11, 2000; "Forum targets future of national parks, Rocky Mountain News, June 1, 1988.

10 "NPS Meeting, or $600,000 Picnic?" Federal Times, May 2, 1988.

11 Memo, Director to Directorate and Field Directorate, April 1988.

12 "Politicians, advocates wrangle over future of national parks," Denver Post, June 5, 1988.

13 Mott tells nation's park managers to promote diversity, Star-Tribune, Casper, Wyoming, June 2, 1988; Superintendents discuss future of nation's parks," Juneau Empire, June 1, 1988.

14 "Vento assails Hodel as Park Service opens conference," Star Tribune, Minneapolis, MN., June 2, 1988.

15 "Political ‘cancer' under Reagan destroying national parks, lawmaker charges," The Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1988.

16 "Vento: Yellowstone officials already have authority to reintroduce wolves," Casper Star Tribune, June 2, 1988.

17 "Parks officials map survival strategy," Rocky Mountain News, June 2, 1988; "Park service leaders deny being hobbled by politics," Phoenix Gazette, June 2 1988.

18 "Vento: Yellowstone officials already have authority to reintroduce wolves," Casper Star Tribune, June 2, 1988.

19 "Park service leaders deny being hobbled by politics," Phoenix Gazette, June 2 1988; Politicians, advocates wrangle over future of national parks," The Denver Post, June 5, 1988.

20 Butler, Prophet of the Parks, pp. 208-209; "Politicians, advocates wrangle over future of national parks," The Denver Post, June 5, 1988.

21 "Take national parks out of Interior, key ally urges," The Sacramento Bee, June 2, 1988.

22 "Expert claims Hodel may be breaking the law if he allows oil, gas leasing in B-T," Casper Star Tribune, June 3, 1988.

23 Ibid.

24 "Law prof: Go to court to save park borders," Tacoma (Wash) News Tribune, June 3, 1988; "Use congressional tools to aid parks, author says," Rocky Mountain News, June 3, 1988.

25 "Imports threaten U.S., Canadian wildlife policies, zoologist says," Casper Star Tribune, June 3, 1988.

26 "National parks urged to blow their own horns, by Charles Seabrook, Atlanta Journal, June 4, 1988; "National parks boom, special needs predicted," Rocky Mountain News, June 4, 1988; "Rosy future envisioned for parks," Denver Post, June 4, 1988.

27 "National parks urged to blow their own horns," Atlanta Journal, June 4, 1988.

28 "Get ready for environmental crises, park bosses told," Rocky Mountain News, June 5, 1988; "High-tech reaching the wilds," Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1988.

29 "Politicians, Advocates wrangle over future of national parks," Denver Post, June 5, 1988.

30 Courier, August 1998, p. 7; "Park chiefs recharge spirits; commitment at NPS reunion," Santa Barbara News Press, June 5, 1988.

31 "Park Service focus shifting from pines to people," San Jose Mercury News, June 13, 1988.

32 "Politicians, advocates wrangle over future of national parks," Denver Post, June 5, 1988.

33 Prophet of the Parks, p. 210; Courier, August 1998, pp. 7-8.

34 Electronic message, Barbee to author, December 11, 2000; electronic message, Joan Anzelmo to author, December 8, 2000.

35 Ridenour, James M. The National Parks Compromised: Pork Barrel Politics and America's Treasures, (Merrillville, IN: ICS Books, Inc., 1994), pp. 67-68.

36 National Park Service, "National Parks for the 21st Century: The Vail Agenda, Report and Recommendations to the Director of the National Park Service," 1992, p. 17.

37 Ibid. pp. 21, 24, 26.

38 Ibid. p. 31.

39 Jerry Rogers review comments. The conference team held their June meeting in the Adams Mark Hotel in St. Louis, where they planned to hold the Discovery 2000 conference. However, planners later learned that a group of African American students had sued the Adams Mark Hotel chain for alleged racial discrimination. The NAACP and later the U.S. Department of Justice joined the suit on behalf of the plaintiffs. Sensitive to the allegations of racial discrimination and the growing media attention, the National Park Service began looking for a new site for its conference and cancelled its contract with the Adams Mark

40 Memo, NPS Director Robert Stanton to Discovery 2000 Participants, December 13, 1999.

41 Author's notes from Discovery 2000, September 11, 2000.

42 Robert Stanton, "Discovery 2000 National Park Service General Conference: Opening Remarks," September 11, 2000.

43 "Dr. John Hope Franklin Encourages NPS to Chart a Proud and Promising Future," No. 2, September 12, 2000, p. 4; author's notes from Discovery 2000, September 11, 2000.

44 "Serving as Stewards of Ancient Heritage in the Century of the Environment," Discovery 2000 Newsletter, No. 3, September 13, 2000, p. 4.

45 "Dr. Peter Raven Outlines Recommendations for NPS Future," ibid., p. 6.

46 "Angelou Wows Crowd," ibid., No. 4, September 14, 2000, p. 1.

47 "Senge: Parks Can Reconnect People," ibid., No. 5, September 15, 2000, p. 3.

48 Robert Stanton, "The National Park Service of Tomorrow: Vision, Challenge, and Exhortation," September 15, 2000.

49 Electronic message, Jerry L. Rogers to Discovery 2000 Participants, September 26, 2000; electronic message, Jerry L. Rogers to Discovery 2000 Participants October 27, 2000.

50 Electronic message, Anzelmo to author, December 8, 2000.

Janet A. McDonnell was formerly the Bureau Historian for the National Park Service in Washington, D.C.