NPS Photo Environmental factors include everything that changes the local environment. This can include anything from natural forces like weather, living park inhabitants, or human interactions like non-biodegradable litter. Any time you visit the park, you have an influence! Every experience you have with nature is uniquely yours. Even if you have been to the park every year, you can see the changes because the environment around us is constantly changing such as weather, time of year, time of day, death and new life, and more. These environmental factors can even vary based on the influence of individual ecosystems and natural features around them. Enjoy the moments as they are, for they will never be exactly the same way again! Some environmental changes are visible, such as a landslide caused by heavy rains. Other changes are not as easy to see. For example, some geologic change, like sediments becoming sedimentary rock, is too slow for the eye to see. Spending time in the park, one can find clues to the changes taking place right before us. While you may not be able to see a glacier move in real time, we witness the effects of these slow changes over time from climate change through studies and observation. Natural Factors:The landscapes of the National Park are in a state of constant change. As water, earth, wind, and fire work independently and together to shape and shift, there are a multitude of forces at work changing Olympic. Every moment of every day, the scenic details are being altered in ways both big and small. These are just a few examples of the many natural forces that are always shaping the land and influence ecosystems:

NPS Photo WaterOne of the leading sources of change at Olympic National Park is water. Whether visitors are hiking to the river valleys and waterfalls or watching the waves along the coast, water is a driving force of nature throughout. The many rivers are largely fed by annual snowmelt and rainfall, as well as the continual runoff from glacial melt coming from the high mountain peaks. Water erodes away the landscape, changing it as the flow follows the path of least resistance. As the waters gradually carve the banks along them, a phenomenon called 'river braiding' occurs. Channels of entertwined streams cut back and forth, widening the river valleys as they snake through. During the rainy season, typically November through March, the rivers swell with rain, often reaching well beyond their banks. This flooding brings with it fallen trees that are swept downstream or out to sea. Roads can even be at risk of being swept away, such as the Elwha road, whose bridges have been swept out before.

While some changes occur over time, some can be much quicker. As you drive along the coast, you may see signs for a "Tsunami evacuation route" posted. Tsunamis are large, fast-moving waves. As the wave mass travels across the ocean, the wave and power behind it increases. Further out in the deep ocean, the waves can travel at 500 mph (800 kph). As it nears the shore, the wave condenses, slowing to 20-30 mph (30-50 kph), still faster than a human can run, but still containing the huge amount of power in what becomes a 10-100 ft (3-30 meter) tall wall of water as it hits land.

Changes will always be occuring throughout Olympic's waterways, but what will it look like in the future? Snowmelt is declining as temperatures increase. Glaciers are melting quickly. Rivers that flow heavily today may decline, leaving people and animals to adjust to a drier peninsula. The park studies water quality in order to ensure safety and understanding today and in the future.

Water is moving; changing. Rivers and glaciers carve out canyons and valleys. Ocean waves grind away cliff sides and create beaches of small rocks and shells. Water freezing in crevices splits cliffs into boulders and boulders into smaller rocks. Much of the natural beauty of the park is formed by water's nourishment. While parts of the peninsula lie in a rainshadow, the moss-laden rainforests found along the Hoh, Queets, and Quinault valleys accumulate an average of 138 inches of rainfall each year. Quenching the thirst of the forest allows for lush foliage to provide food and shelter for the wildlife of the park, as well as photo opportunities for visitors.

NPS Photo EarthWith mountain peaks, coastal spires, and literally everything in between, Olympic National Park is a geologic hub of yesterday, today, and tomorrow. The mountains are uplifting as the river valleys are being carved out. While much of geology moves too slowly to be witnessed in a single lifetime, some changes can occur in the blink of an eye. The changes can be drastic or minute, but every moment, this Earth and landscape are moving. The Olympic Peninsula lies in the subduction zone between two tectonic plates, the North American Plate and the Juan de Fuca Plate, where they converge. As one folds under, it pushes the Olympic Mountains higher. This action can shake the earth, causing Earthquakes, particularly to the South and the West in the Pacific Ocean. While earthquakes are rarely felt in the park, there is a faultline nearby, making them possible in the park and more common just a short distance away. Earthquakes shape and shift the earth on site. These are only one driving force of change! Some of these changes can cause residual damage as well.

Tremors underneath the ground, as well as continual erosion, can cause sections of mountains to let go. When this happens, rock and debris may be sent cascading downhill in the form of a rock slide. Trees and trails can be swept away in an instance with nothing more than a bare scar left as a reminder of what once covered the hillside. When hiking along the hillsides of Olympic, remember to watch for loose ground and stay on trails to prevent erosion and stay safe.

Glaciers in Olympic today are receding. As the force of these massive ice blocks moves over the land, it changes it. A glacier can grind the rock below its weight or leave behind debris from pebbles to erratics as large as a house. This constant glacial movement carves out valleys and rounds out saddles between peaks, leaving a noticeable mark on the land.

As mountains continue to rise and glaciers continue to recede, the shapes and figures of the geologic giants change each year. Visitors come from all around to witness the geology of Olympic. Whether it is for the snow-capped mountain peaks and rock spires that stand out against their backgrounds of open sky and ocean, or for the lush forests, ever influenced by the valleys and rocky soil, visitors witness the magic of influence from geologic change throughout the entire park. As you continue the journey of learning about the earth, remember to leave no stone unturned!

NPS Photo WindCan you picture the effects of wind? It may be a gentle breeze on your cheek, a gust that blows your hat off, or raging top-speed winds that can almost knock you to the ground. Wind can come in many forms, but will change the earth with every breath. As the wind blows through the valleys, it can pick up strength. As more power is added, some gusts may become formidable forces that alter the land around them. Howling through the forests, the giant trees sway and bend with the winding wind. However, on occasion, these wind storms can be powerful enough to knock down lone trees or even entire swaths of forest, opening the dark floor to new beams of forgotten sunlight. Of course, no matter the devastating effects, the aftermath may allow for new growth to foster in an area once reigned by the giants of the forest.

Wind does not just destroy, but can help to spread life. Many plants rely on gusts to push their young seeds to new, fertile soil. This may even land atop a freshly fallen tree from a wind storm that can then become a nursery log as it nurtures the seeds from its nutrients. Wind is not only localized, but can carry with it stories in many forms. As fires rage even in other states, wind can carry the smoke across the region, clouding the skies and reducing air quality for miles.

While wind can alter by destroying or creating, it can also alter by encouraging resistance through adaptations. One of the best examples is seen in the trees that can adapt to such a windy way of life. Some trees endure by bending to the wind's will and allowing their needles and branches to grow where the wind pushes them. Trees that are hundreds of years old may trick the eye as they stay low to the ground, their growth stunted, but their ability to keep from crashing down ever increased. These adaptations can be seen atop Hurricane Ridge, as the gnarled trunks of the evergreens have been twisted by the wind's might. There have been historic records of wind speeds reaching up to 80 mph (129 km/h), giving the ridge its name. With almost contant winds coming in from the ocean, coastal trees may adapt in a similar manner, becoming gnarled and twisted as they sway to the salty sea breeze.

Wind may carry more than dust as it chips away and brings change to massive rocks that become smaller over time. This can be especially noticeable on the coastal shores as windswept sands blow past. When wind is contained or consistent, major erosion can be seen. From stripped rock faces to a gaping hole beneath a tree on the coast line, wind, often combined with other elements, can leave many a mark before blowing on by.

Wind presence and speed may vary by day, but its presence overall is a constant factor of change. As you return to the park or see photos over time, look for the changes that may be caused by the most fervent blows or the quietest whisper of the winds.

NPS Photo FireFire is a natural part of succession through ecosystems. Even in a rainforest, there is a dry season through the summer months where the land can become parched. Fire appears to scar the land, but, like all natural elements, it plays more than one role throughout the park. After a fire ignites, it can smolder or spread with intensity. Many fires are started from lightning strikes. These are a natural occurance that changes the land. Some vegetation may get singed, while other plants may die from the heat and flames. Some plants have adaptations for fire resistence such as the Douglas Fir, whose extremely thick outer layer of bark can deter the flames from catching on its wood. While fire spreads, the smoke can be seen from miles away, allowing for onlookers to understand the current activity.

Fire can cleanse an ecosystem, allowing for regeneration and regrowth on a now-blank canvas. Sun-loving trees will flourish in an open field and some flowers particularly love recently heated ground. What may have been old-growth stands can give way for a new generation of giants to begin their story and build a new forest home as they take visitors along with them.

Humans will always play a role. While many camping areas allow fires, not all do so be sure to plan ahead. Human-started fires have happened in the park, leaving unnatural scars in their wake. As these can spread rapidly, visitors are asked to fully extinguish any flame or ember before continuing to explore the ever-changing Olympics. The Elements TogetherOf course none of these natural factors are influencing the landscape alone. Erosion and deposition can come in many forms. Changes to the forest can come from fire, wind, or water changing course. No matter where you go in Olympic National Park or the world, the environment and its factors are interwoven, creating a tapestry that tells a story of the past, present, and, if you observe carefully, the future.

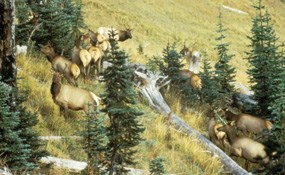

NPS Photo Plants and AnimalsPlants and animals are abundant throughout Olympic National Park, breathing color and life into every habitat. As they grow, they change their ecosystem along with themselves. Plants and animals will influence and can be influenced by each other, the geology and elements, and the people that visit.

NPS Photo Human Effects:The national parks are set aside for the benefit and enjoyment of the people as well as to preserve and protect the natural world. Within that balance, people play an important role. Humans influence their environment by simply being there. Any given moment in nature, a person may have a positive or negative affect on their surroundings. Throughout Olympic National Park, visitors can show their positive natural influence in many ways! Utilizing Park Infrastructure Park management is seen across the front country of Olympic. Roads, trails, and buidlings that people use and enjoy each day have an overall impact. Not only do they define where plants and animals can and cannot live, they direct visitors to specific parts of the landscape. Over 95% of Olympic National Park is designated wilderness. As defined by the 1964 Wilderness Act, a wilderness is "...an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain." While visitors may not create the roads or buildings, people often have a say on proposed changes to the parks.

Olympic National Park sees over 3 million visitors on average. With over 600 miles of trails designed to explore and view fantastic sights, there are numerous opportunities to explore areas close to the roads or far in the backcountry. Visitors love to see all there is to see in Olympic. Please remember to leave as little impact when exploring these natural spaces to protect the landscape and prevent social trails.

Wildlife watching is just one of the many ways to enjoy the park. Olympic has a variety of wildlife from the forest to the ocean that can be seen throughout the year. Stay safe and informed by learning more about wildlife spotting tips and tricks. Some are elusive, and others quite common, but National Park wildlife is meant to be wild. Feeding human food to animals can make them dependent and less able to forage on their own. Once accustomed to humans, larger animals like deer or bears can become dangerous in their search for food. While visitors don't want to get too close, be sure to respect the homes of the animals. Making noise is a great way to be safe, but scaring wildlife with loud noises or altering their habitat can affect where and how they live.

When people come to the park, they may hope to see mountains, rivers, glaciers, forests and oceans. These natural views can be impeded by trash or remains of those that came before. Leaving evidence of your time in nature can impede people, animals, and vegetation alike for years. Non-natural items that get into the ocean may be out of reach from helping hands, creating a greater danger for sealife to swallow or get caught in. One of Olympic's best community efforts revolves around coastal cleanups! With over 3 million visitors per year on average, Olympic and its visitors work hard to maintain a natural ecosystem.

Litter can be anything not naturally occuring in the ecosystem. From trash, to invasive seeds, to painted rocks, to fires left smoldering, people can prevent many issues that can occur. Taking plants, animals, and even rocks or twigs from the park ecosystems can kill them, leave a lack of food or shelter for animals, and lessen the beauty of the diverse ecosystems for other visitors. Remeber that with millions of visitors each year, Olympic is for all to enjoy and may not last should every person leave with a piece of it.

Some larger impacts can be made over time. Aside from litter or damage one may see, other impacts can sometimes go unnoticed. Whether in the park or at home, people may use lights, make noise, and use tools. Light pollution is minimized in many areas with downward facing lighting fixtures and automated lights. Olympic has a large part of its landscape that is far from roads and other infrastructure where people and cars create sound, and the density of the park's lush forests dampens natural noises as well. Sounds can change visitor and animal behaviours alike. Helping to keep the wilderness wild comes in a variety of ways, including maintaining natural nightskies and soundscapes.

People all have a carbon footprint left behind based on the amount they use and produce. Automobiles and industry put tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that can eventually cause worldwide temperatures to rise and glaciers to melt.

Chemical runoff, sedimentation, and accumulation of nitrogen in mountain lakes influence water quality in Olympic National Park. Olympic is known for its blue rivers and lakes, deep salty coastline, and clear natural springs. Thank you for leaving a positive impact!

|

Last updated: September 27, 2020