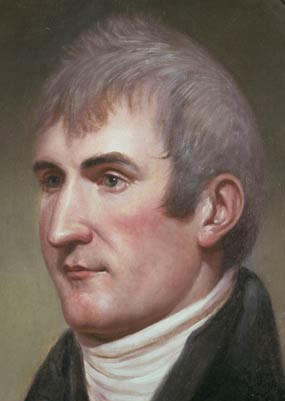

Charles Willson Peale Portrait From a young child in Virginia to Governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory, Meriwether Lewis led a life full of challenges and opportunities. The discipline of the military and his formal education prepared him to work for President Thomas Jefferson as his personal secretary. He had the initiative to lead an expedition into unknown territory, and was rewarded with the honors that came along with the risk. Upon completion of the expedition, he was appointed Governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory. Though his life ended early along the Natchez Trace, he played an integral role in shaping the American West. Early Life Born August 18, 1774, near Charlottesville, Virginia, Meriwether Lewis began a life of adventure. As the second child of William and Lucy Lewis, he encountered many challenges during his youth. After losing his father at a young age, his mother remarried, and the family moved to Georgia. The young, inquisitive Meriwether explored the countryside and showed an interest in natural history. Lewis chose to return to Albemarle County, Virginia to obtain his formal education and learn how to manage the family plantation. He began his service to his country by enlisting in the military and joining the forces seeking to put a stop to the Whiskey Rebellion. He served with William Clark, the commander of the Chosen Rifle Company of elite riflemen. Lewis quickly rose to the rank of Captain, but didn’t forget the bonds he formed. His formal education, leadership skills, and experiences made him the perfect choice to work side by side with President Thomas Jefferson as his personal secretary. A Leader Emerges President Jefferson was interested in sending an expedition to explore the land west of the Mississippi River. While working at the White House, Lewis proved that he was the perfect candidate to look for a commercial water route to the Pacific Ocean. Lewis had an opportunity to learn diplomacy firsthand while living and working in the White House. In preparation for this expedition, Jefferson arranged for Lewis to learn from the top botanists, physicians, and scientists of the time. He was responsible for gathering supplies and chose a co-captain to lead the expedition. William Clark was willing to take on the risks and honors that would come along with leading this journey. The Corps of Volunteers for Northwestern Discovery, today known as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, was a military expedition, and military values like respect, honor, and integrity were instrumental to the success of the expedition. The Adventure of a Lifetime The primary purpose of the expedition was to find and map an all-water route to the Pacific Ocean. The 35 members of the expedition had multiple responsibilities. They were diplomats, sent to establish peaceful relationships with the Native American tribes they encountered. They were scientists, sent to document the plants, animals, rocks, and minerals that they found. They were navigators, using crude instruments to make accurate maps of the route. Imagine a group of men leaving St. Louis, traveling across the continent into unknown territory. They fought the current of the Missouri River in the summer heat, crossed the Bitterroot Mountains in the bitter cold. Their boats needed to be portaged around waterfalls and new canoes needed to be dug out by hand. Members of the expedition dealt with constant physical challenges, including frequent malnutrition, swarms of mosquitoes, and biting fleas that made even the simplest task more difficult. After a long day of traveling the captains and sergeants were responsible for documenting the daily events in their journals. There were times when Lewis was a very diligent writer, and other times when he did not write at all. What could have prevented him from documenting each day of the trip? Did it get too tedious, or was there another reason for not writing? Modern historians can only guess why Lewis left gaps in the expedition journals. From Explorer to Governor After completing nearly 8,000 miles by boat, horseback, and on foot, the members of the expedition returned to St. Louis in September of 1806 without ever finding the all-water route to the Pacific Ocean. However, they documented and described for science 122 animal species and 178 plant species. They came in contact with about 50 American Indian tribes. A map was created, and many years later, journals were published. President Jefferson rewarded Lewis by appointing him Governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory. When Lewis arrived in St. Louis in March of 1808, he encountered new challenges. Lewis was now in charge of the land he recently had the opportunity to explore. There was tension between Lewis and the Secretary of the Louisiana Territory, Frederick Bates. They had different political views, and different opinions on policy. In 1809, the new Madison administration imposed a stricter financial approval process on territorial governors. Payment vouchers approved under Jefferson were largely denied by the new administration. The administration denied several of Lewis’ bills, leaving him personally liable for their payment. Facing dishonor and personal bankruptcy, Lewis started on a trip to Washington, D.C., to resolve the issues. Lewis’ Last Journey In September of 1809, Lewis began his journey to Washington, D.C., to document and defend his spending of government funds, publish the expedition journals, and meet with former President Thomas Jefferson. While traveling, he wrote his will, leaving his possessions to his mother Lucy Marks. At Fort Pickering, near modern day Memphis, Tennessee, Lewis and his traveling companions met with James Neelly, the Chickasaw agent who would escort them through Chickasaw territory. He then traveled through the remote wilderness along the Natchez Trace north to Grinder’s Stand, an inn run by the Grinder family. Mrs. Grinder prepared a meal that evening, and made up a room for Lewis. Later that evening gunshots were heard, and Lewis was found with two gunshot wounds: one to the head, and one to the chest. Lewis’s life ended on the morning of October 11, 1809 at the age of 35. Many who knew Lewis at the time of his death believed he had taken his own life. Recorded circumstances of his death indicate the probability of suicide; however, some accounts dated 1848 and later suggest Lewis may have been murdered. Meriwether Lewis's People

|

Last updated: September 27, 2021