On a cold, snowy day on Dec. 16, 1944, many inexperienced American soldiers stationed along the German border and in the heavily wooded Ardennes forest in Belgium, Luxembourg were surprised by the attack of Adolf Hitler's soldiers.

The Allies landed in Normandy on June 6, 1944. They advanced to liberate Paris on Aug. 25, 1944, and continued on to drive the Germans back toward Germany. In response to this Allied push, Hitler planned to drive a wedge between the American and British forces in Western Europe, initiating the Battle of the Bulge. This battle took its name from a bulge 70 miles wide and 50 miles deep created in the Allied lines when the Germans moved into the Ardennes. Hitler's offensive would be his last gamble of the war.

The Battle of the Bulge developed as the Germans encircled the town of Bastogne, Belgium. One of those Americans who remembered those cold, snowy days, and who also received a copy of the famous offer of surrender of Bastogne, was my father, Thomas R. O'Brian, who was a member of the 775th Field Artillery Battalion. As I was growing up he would tell me, my four sisters, and two brothers about his WWII experiences, and especially about the Battle of the Bulge.

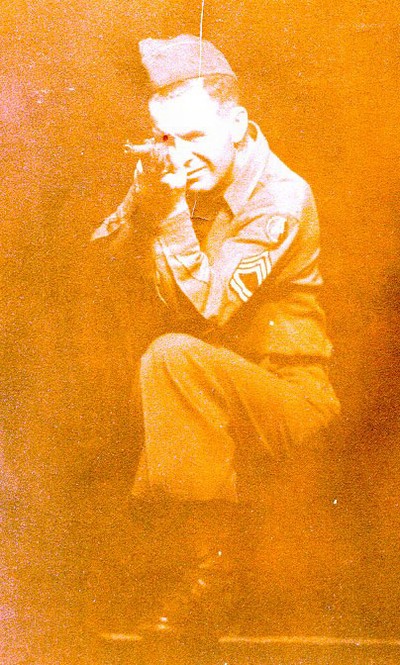

Thomas O'Brian

His battalion and the 101st Airborne Division, along with attached units such as the 10th Armored Division, Combat Command B, the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, Company C, 9th Armored Engineers, 969 Field Artillery Battalion, Combat Command R(37th Battalion), and the 4th Armored Division all had the duty of defending Bastogne. The battalion was split with one group in Bastogne itself, and my father's group near the village of Villeroux. The village was southwest within a short distance from Bastogne. They were stationed there primarily because they had 155mm howitzer guns which could fire three times longer than the airborne artillery could fire. The 155mm howitzer guns were very effective in destroying German tanks when they were on target. Fighting was constant, and the troops began to be cut off as the Germans pushed forward. My mother received letters regularly from my father throughout the war until his battalion was sent to Villeroux.

Temperatures began to plummet as winter neared. My father tried to stay warm by stuffing newspapers inside his summer uniform, which consisted of a meager light jacket. He always said when it became cold and snow was on the ground, that it reminded him of Bastogne. On Dec. 19, 1944, the Germans attacked the defensive boundary of Bastogne including Villeroux. The Americans responded with force. If they could not destroy German tanks with their 155mm guns there was another method of destroying them: by firing bazookas on the treads of their tanks. Then some brave soldier would volunteer to go behind the tank, open the top hatch, and drop grenades inside to knock it out. My father told me they had to do this more than once.

Villeroux was cut off from Bastogne for four days starting the next day, Dec. 20. As the Germans entered into Villeroux my father and fellow soldiers hid in a basement of a house while German soldiers were just outside. In addition to battling the cold and German forces, they had to fight off the rats crawling on the floor as they sought refuge in that basement. My father had a carbine rifle as his only weapon to fight the Germans. That same day Bastogne was surrounded by the Germans.

Battle of the Bulge bas relief panel at the World War II Memorial

Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe, who was the acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division, organized the defense of Bastogne. The Americans were low on medical supplies, warm food, warm clothing, and ammunition. In addition to the Germans surrounding his defenses of Bastogne, they also bombed the town at night. This added to the soldiers already wounded from the fighting around Bastogne. Civilians of Bastogne, who also were trapped in the siege, became part of the wounded from the bombing. Despite all of these problems, McAuliffe received a surrender offer from the Germans on Dec. 22, 1944. He was not exactly sure how to react. Initially, he responded by saying, "Aw, Nuts!" It seemed funny to him at the time. He realized he had to reply back within the two hours or the Germans would continue their attack. "Well, I don't know what to tell them", he said to his staff. Col. Harry W.O. Kinnard, the 101st's operations officer, said to McAuliffe, "The first remark of yours would be hard to beat." McAuliffe was not quite sure what he meant at first, then, Kinnard said to him, "You said 'Nuts!'" The staff applauded, and McAuliffe decided to send this message to the Germans, "To the German Commander, NUTS! The American Commander."

The response from McAuliffe's staff was laughter, and then Col. Joseph Harper, a regimental commander in the 101st, carried the message back to the Germans. Two German officers did not quite understand the message and Harper told him, "If you don't understand what 'Nuts' means, in plain English it is the same as 'Go to hell.' A German major and captain saluted very stiffly. The captain said, "We will kill many Americans. This is war." Harper said, "On your way, Bud, and good luck to you." Harper did regret in an interview after the siege of saying good luck to the Germans.

On Dec. 23, 1944, my father and his fellow soldiers were able to get out of the basement that they were in, and received a morale boost. They were joined with other American soldiers and received a mimeographed copy of the surrender story. They got a good laugh from it. The fighting continued through Christmas. They heard rumors about Gen. George S. Patton's men coming to lift the siege.

The encirclement of Bastogne was lifted on Dec. 26, 1944, when Patton's 4th Armored Division broke through the German lines. My father was guard duty at night when Patton was approaching the American lines, and he met the general. When the movie Patton was released in 1970, my father took me and one of my brothers, Dan, to see it. He said the movie was very close to the real Patton. He always complained about Hollywood's version of WWII, but he was satisfied with the movie. After the siege was lifted my father and his battalion became part of the XII Corps of Patton's 3rd Army which advanced into the liberation of Germany.

The World War II Memorial represents an American generation that was involved in the Second World War, whether on a war front like the Battle of the Bulge or a home front. It also represents courage and sacrifice. Along the Northern entrance walkway, there is a bas relief panel exemplifying this famous battle, honoring 19,000 Americans who died. My father came home in Oct. 1945, after Germany surrendered in May. Unfortunately, he died in 1976, so he did not have a chance to see the World War II Memorial. So when I see that particular panel in the memorial set in bronze, I appreciate my father's courage especially with those cold, snowy days of 1945 in mind.