Keith Rocco / NPS

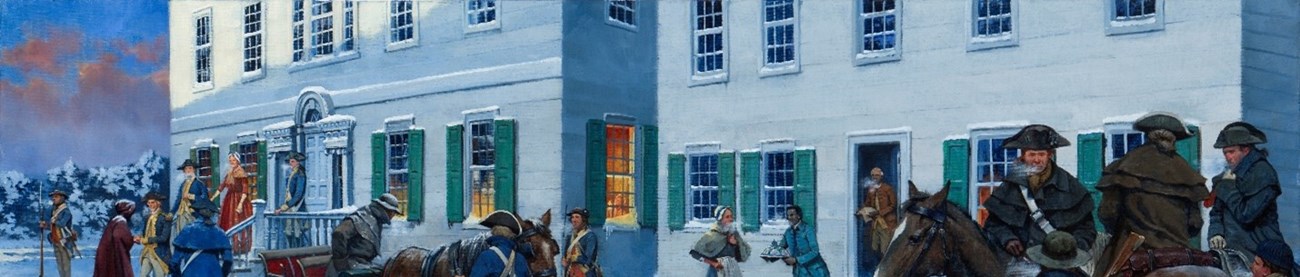

As we look at the picture closely and carefully, we must ask ourselves: 1. Does anything or anyone in this picture conflict with the historical record? 2. Are the people portrayed realistically in authentic settings? What are they wearing? What are they doing? What is their relationship to other people in the painting? 3. What assumptions does the NPS/Rocco make and are they supported by the historical record? 4. How well does NPS/Rocco integrate historical facts into his artistic imagination? Continue reading and find out how the National Park Service and Artist Keith Rocco has interpreted the story of Mrs. Washington’s arrival at the Ford Mansion.

Keith Rocco / NPS

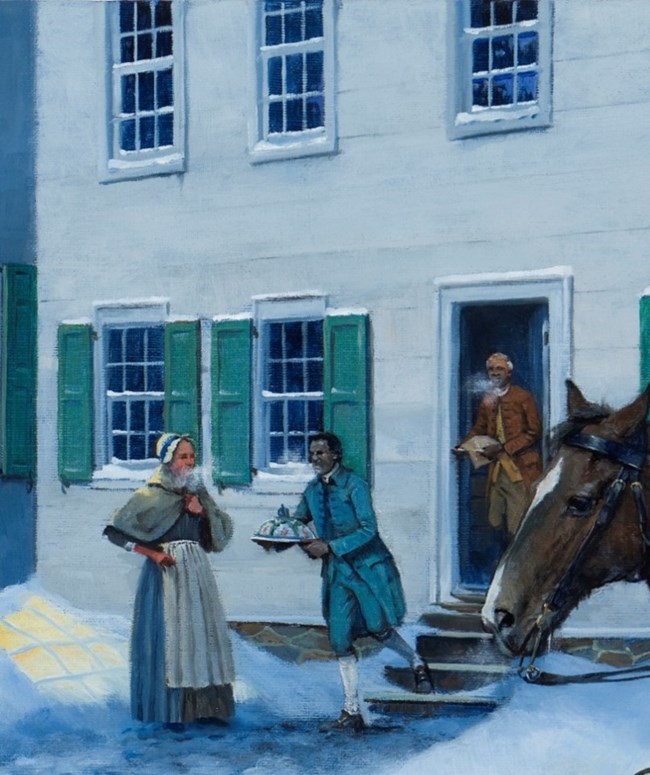

Major Caleb Gibbs, the commander of the General’s Life Guards stands between the stairs and the sleigh. Mrs. Washington’s coach could not get out of Philadelphia due to deep snow; Gibbs was sent with a sleigh to bring her to Morristown. It took them two days to reach Morristown. General Washington struggled to maintain troop morale and discipline under harsh conditions in Morristown in 1779: bitter cold, disease, and lack of provisions. Washington believed that uniforms represented the army’s professionalism and discipline. The Rocco painting accurately depicts Washington’s wool uniform worn from 1789-1799 and Mrs. Washington’s wool cloak worn over what was probably a wool dress for warmth. Both Mrs. Washington and Mrs. Ford wear practical everyday dresses rather than formal gowns. To keep off the cold while traveling in an open sleigh, Mrs. Washington wears a heavy hooded, wool cape. Mrs. Ford has stepped out quickly and has merely thrown a wool cape over her shoulders. Mrs. Ford’s informal attire reveals that she has much work to do in her household which had been transformed from a family home for four people and a few enslaved servants to a military headquarters for Washington’s entourage of approximately 30 people (five aide-de-camp and more than eighteen servants and enslaved people, including William Lee, his enslaved valet). The house became two separate households – Washington’s and Mrs. Ford. Mrs. Ford was responsible for the food and shelter for everyone in her own household – herself, Timothy [age 17], Gabriel [age 15], Elizabeth [age 12] and Jacob III [age 8] and as many as three enslaved people, Pompey [age unknown], Jack [age 51] and Phillis [age 55]. Washington’s 18 enslaved and free Servants handled all the cooking and household needs of the military family and his guests.

Keith Rocco / NPS

Keith Rocco / NPS The woman watching the two servants is Mrs. Thompson, the 76-year- old Irish housekeeper who supervised Washington’s kitchen. Note that while Washington and his enslaved servants are dressed for a formal dinner, Mrs. Ford’s clothing is an ordinary, informal, day dress, inappropriate for a formal dinner.

Keith Rocco / NPS

Keith Rocco / NPS After taking a closer look at the painting, what have you learned about the arrival of Mrs. Washington at the Ford Mansion? Have any of your ideas about Washington’s time at the Ford Mansion changed? What else would you like to learn or ask a question about? Feel free to e-mail us |

Last updated: November 9, 2022