Place Names and Traditional Land Use

Inupiaq Eskimo and Athabascan Indian peoples have, for millennia, inhabited, utilized, or traveled across the lands of northwest Alaska. Long ago and even up to the 1920s and 30s, small groups of families were semi-nomadic, moving with the seasons to be strategically located near subsistence resources. During their lifetimes, some people traveled quite far and became intimately familiar with astonishingly vast landscapes. A prime recorded example of this is the life of Joe Immaq Sun of Shungnak whose knowledge has been preserved in a variety of reports and documentary films.

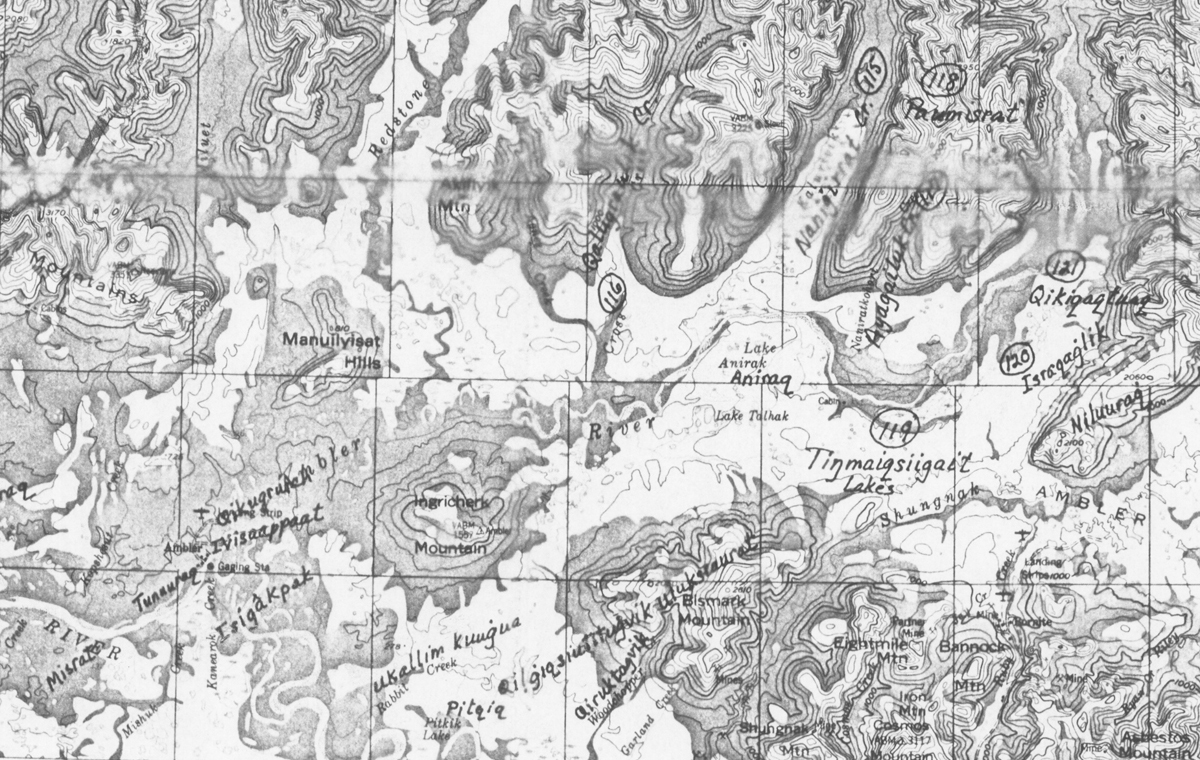

Place names collected on a map as part of the Joe Sun collection.

Modern USGS topographic maps for Alaska contain few annotations. From looking at these maps one might assume that few features within these vast landscapes were ever visited or named by peoples in the past. This, however, is a false assumption. Documented traditional place names, tales, land use patterns and oral histories exist for northwest Alaska, as well as many other areas of the state. These studies provide a wealth of information about past and present cultural connections to the lands and resources of Western Arctic National Parklands and beyond.

Since at least the 1960s, various Inupiaq and university scholars have attempted to systematically record such knowledge but the products of their work may be somewhat difficult to find. Few were distributed even at a local level. Sometimes limited distribution was due to the sensitive nature of the information although some were simply limited by available technology, publication costs or by the fact that they were small projects that didn’t lend themselves to mass distribution.

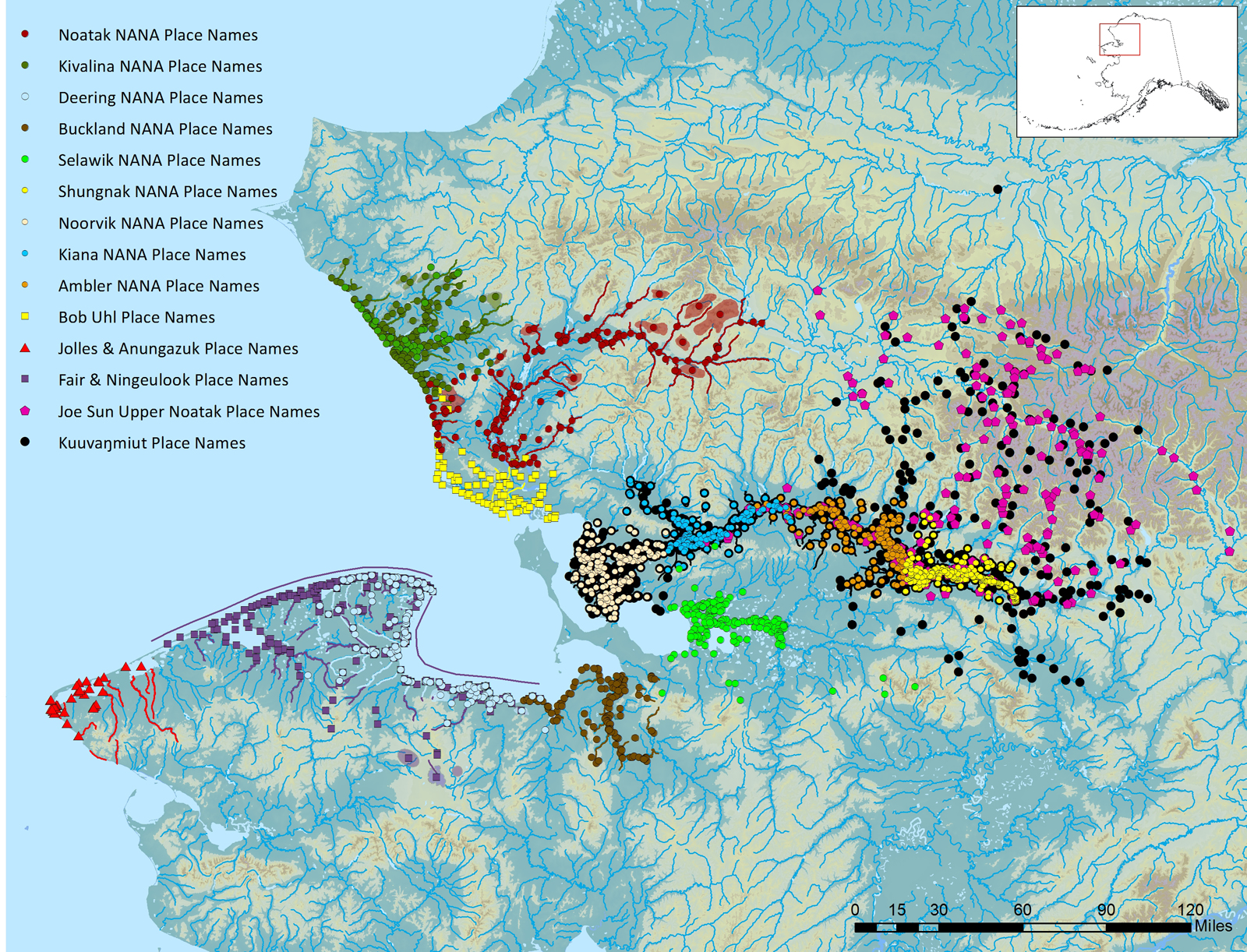

The National Park Service financially supported several place name documentation projects in the region during the 1970s and 1990s. For a number of years, the staff has been working to identify existing Inupiaq place names data sets that may be suited for digitization into a Geographic Information System (GIS). GIS is a particularly useful way to share information about geographic features and landscapes. Although issues of cultural sensitivities may limit the degree to which the data is distributed and shared, Native communities who created the data will certainly benefit from the consolidation of this type of information into a GIS format.

A GIS map displays layers of data. In this case, each location that was identified in a place name project is shown as a dot of a particular color.

Each study is done differently, depending upon the goals of the project, who collected the information, who was available to contribute information, the depth of knowledge of contributors, financial considerations and a host of other factors.

In some cases, only names are recorded on maps. But most often projects involve far more than simple recordation of names associated with places.

For example, a literal translation of the name may be provided, such as place name number 253 in Kuuvangmiut Subsistence: Traditional Eskimo Life in the Latter Twentieth Century:

Itivliq. “portage place,” in this instance a portage between Hogazta and Pah Rivers.

In other cases, an associated story may be included, as was the case for Pannavik recorded by Joe Sun:

“Further upriver there is a small mountain with a pointed top. It is called Pannavik. It is said a man climbed up there to gaze over the mountains. He had his two-edged spear pointing up. He was jumping trying to get a better view down to the river and he landed on his spear and killed himself. That is why they call it Pannavik’ (Joe Sun). [‘pana’ is something real sharp; ‘panatit’ means to get pricked or when something real sharp penetrates your skin]”

Bob Uhl Place Name #31: Napaaksaq, a.k.a. Sealing Point Tower. Uhl states: “The tower at the tip of the cape at Cape Krusenstern. There have been at least two towers built on this site by local people and the present one was started, but not yet finished, with the help of Park Service. In the past, the towers were used by seal hunters for locating open water and by reindeer herders and hunters to locate animals or game on the flat lands of the beach ridge complex. Aircraft may orient their position in relation to Napaaksaq in times of poor visibility.” NPS Photo

Sometimes a name provides an indication that the place, now associated with one population, was once, or perhaps remains, associated with another. At times a place may even be known to one group only by the name assigned by previous inhabitants. For example, number 233 in Kuuvangmiut Subsistence: Traditional Eskimo Life in the Latter Twentieth Century:

Taaɫaɫhiarautit, “a gravel bluff (Indian name)”

Quite often names are associated with subsistence activities, such as hunting, fishing and gathering. A name may be illustrative and to the point, such as Nigaqtuġvik, “place for snare.”

NANA Shungnak NANA Place Name #129: Qikiqtaqpak, Lit. big island, refers to the island upstream from (above and to the right of) the person. NPS Photo: E. Devinney

Some provide information about changing features within the landscape, such as Kuuvangmiut Subsistence place name #158:

Siiqaqtuaq, “used to have sheefish.” An older lakebed west of Pitqiq Lake.

Additional details may be offered to describe how a place was used or described:

“Quviqsugaurat, Literally: cranberry pit. A method how cranberries were stored. This area produces cranberries, and around this area was where pits were dug. The pits were lined with moss, and filled with berries, and covered again with moss. The pit is called quvisgauraq. The round hills with birch trees. The shaded green areas are Quviqsugaurat.” (Shungnak, NANA Place Names Project)

Eileen Devinney at the Great Kobuk Sand Dunes, NPS Photo

About the Author

Eileen Devinney has worked in the Alaska Region of the National Park Service for over 20 years, half of that in service to the parks and peoples of northwest Alaska. While working at Western Arctic National Parklands she provided technical assistance to communities, taught courses and workshops in the documentation of cultural knowledge, took part in door to door subsistence harvest surveys and managed the park cultural resource program which included oversight of archeological, anthropological and historical research and documentation. In her current position as Anthropologist and regional NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) Coordinator she provides assistance to all of Alaska’s parks, including those in the far northwest.

The Great Kobuk Sand Dunes in Kobuk Valley National Park, a.k.a. Ambler NANA Place Name #135 Qaviat Qaviaġruich, Lit. big sand dunes. Joe Sun just called it Qaviat. Photo: E. Devinney, NPS