Prior to 2006, Katmai’s spruce forests appeared healthy. Under the dense canopy of needles, little light filtered through to the forest floor where mosses and shade tolerant shrubs held a dominant foothold. Reaching toward the sky were many spires of green-needled spruces that intercepted much of the incoming light.

Katmai's spruce forest appeared healthy less than a decade ago. (NPS Photo)

Katmai's spruce forest appeared healthy less than a decade ago. (NPS Photo)

Today, however, even the casual observer walking through those same forests will find something amiss. The standing spruce are now dead skeletons of their former selves. Light easily reaches the forest floor. Mosses are being overtaken by vigorous grasses and tall shrubs. Something swept through this forest, and like a pandemic strain of flu, it killed most of its victims. What happened to these trees? How could they change so rapidly? The trees died because another organism, the spruce bark beetle (Dendroctonus ruftpennis), was trying to survive.

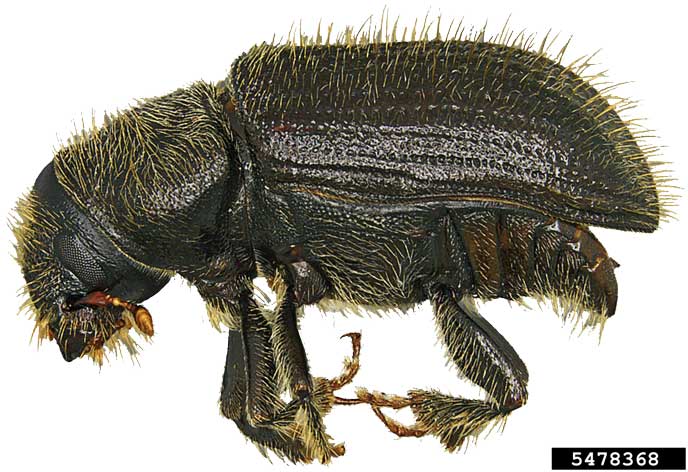

Small insects like, bark beetles, can have extensive impacts on forests. (Steven Valley, Oregon Department of Agriculture, Bugwood.org)

Spruce Bark Beetle Basics

Adult spruce beetles are are about .25 in (6 mm) long and are dark brown to black, with reddish brown to black wing covers. They generally have a two-year life cycle spending one winter as larvae and their second winter as adults. After the second winter, adults emerge in late spring or early summer. Females bore into the bark of trees and construct a gallery. Eggs are deposited on either side of her gallery. Larvae emerge and feed on phloem, a layer of living wood that transports food up and down the stem of trees. They feed outward from the gallery in a radiating pattern. If beetle larvae densities are high enough, they can girdle and kill the tree as they feed

High densities of bark beetle larva feeding on inner bark can quickly girdle a tree. Numbers at the bottom of the photo indicate centimeters. Small holes (see inset) in the bark mark the locations of emerging adult beetles. (NPS/M. Fitz)

Beetles and Spruce in Katmai

White spruce (Picea glauca) are the most abundant conifer in Katmai. They are well adapted to reproducing and surviving in cold climates with short growing seasons. A conical shape and branches that flex downward help these trees shed heavy loads of snow and ice. Evergreen needles can photosynthesize as soon conditions allow. Plus, the abundant, sticky pitch running under the bark is a strong defense against invading insects.

Unlike the interior of Alaska, natural fires in Katmai are almost unheard of. Strong windstorms and the occasional volcanic eruption can kill forests, but bark beetles are the biggest threat to Katmai’s spruce trees. Of course, certain insects make a living off of trees and white spruce is no exception. Bark beetles preferentially attack recently fallen spruce trees. When conditions are right, however, their numbers can explode and kill whole stands of trees.

From 2005-2007 this happened in Katmai. Spruce bark beetles overwhelmed the defenses of living trees, their larvae girdled them, and the trees died. Now the walk to Brooks Falls or on the portage trail near Fure’s Cabin is through a forest where more than 75% of the mature, standing spruce are dead.

But, what made the trees so susceptible to beetle attack? Trees cannot run or hide, so they must have a way to defend themselves. As it turns out, they do. Spruce bark beetles are always present in Katmai’s forests. Usually, their numbers are checked by winter temperatures below -15˚F (-26˚C) and predators like woodpeckers. Spruce trees can also defend themselves by filling the beetle galleries with pitch that either entraps or pushes the beetles out. Imagine being a 6 mm long insect struggling against the viscous pitch of a vigorously growing spruce tree. When beetle numbers are low and when growing conditions for the trees are favorable, spruces may not suffer much from beetle attack.

But bark beetles are survivalists. They are adapted to take advantage of favorable conditions. Bark beetles are good at killing large, slowly growing trees. Adult beetles also attack trees late in the spring and early in the summer when soil temperatures may be low and the weather may be dry and warm—a combination of factors that suppresses a tree’s growth but favors the beetle. Also, if temperatures are warm enough bark beetles may complete their life cycle in one year instead of two. Many of Katmai’s spruce forests, and especially the spruce forest at Brooks Camp, were growing in even-aged stands where the trees were all about the same age and size. Trees in an even-aged stands can all be weakened by the same factor like drought or just competition with its neighbors for light. Drought, competition with other trees, and warm springtime temperatures are a potent recipe for a bark beetle explosion.

End Game?

For decades before 2006, bark beetles lurked in the forest, eking out a living when conditions were less than favorable. When a combination of warmer-than-average temperatures and drought caught up with the stands of older, even-aged trees, the beetle population erupted and took advantage of the situation.

After one summer of high beetle numbers, the dark green needles of many spruces started to fade. The trees were trying to defend themselves, using sticky pitch in a fight for survival, but this time they couldn’t hold the line against overwhelming numbers of beetles. By the second year, their needles turned reddish-brown and fell to the ground. A new generation of beetle larvae were at work by then and many of the remaining trees would soon succumb. Now a walk to Brooks Falls takes you through a forest that is a ghost of its former self.

Hundreds of dead, standing spruce line the trail to Brooks Falls (NPS/M. Fitz)

But is this the end of the story? Yes and no. As huge numbers of beetles kill more and more trees, they may eat themselves out of house and home. Spruce bark beetles do not feed on dead wood, nor do they reproduce well in smaller, faster growing trees. Once the live trees are gone, beetle populations crash. They may not recover for many decades until the right combination of favorable conditions is met once again.

Forest ecologists, using tree ring data, have determined that bark beetles erupt in south-central and southwest Alaska’s spruce forests every 50-100 years. Outbreaks tend to occur over a few years and then taper off. Past outbreaks didn’t seem to be as intense as this latest battle though, and this time the beetles certainly got the upper hand.

The boom of the beetles was an epidemic, but only from a human perspective. Certainly, Katmai’s spruces suffered, but the beetles are not an invasive species from another continent that are fundamentally changing the region’s ecology. They are just another animal trying make a living. The larger, slower growing trees may have suffered, but the opened canopy created opportunities for the next generation of spruce to gain a foothold. Bark beetles may seem like little monsters, but the beetles, like humans, simply take advantage of favorable conditions in order to reproduce and survive.