Ice Age Floods

Study of Alternatives

Section J—Interpretation |

Introduction

| |

Tours arranged by the Ice Age Floods Institute bring the visitors face-to-face with the evidence of the Ice Age Floods. At Wilson Creek, the visitor can appreciate Bretz’s analysis and understand the Floods’ impact on the land. (Photo: M. Sear/Columbia Basin Herald)

|

The Organic Act of 1916, which created the National Park Service, charged the NPS with not only the task of preserving and protecting the parks’ resources, but also to “provide for the enjoyment of the same.” The “enjoyment” mandate has come to mean interpreting the meaning and value of the parks’ resources to the public. In most cases, interpretation can be provided on-site unless the area is too small or the resources too fragile. The larger the park or area and the larger the number of resources contained in that area, the more complex the interpretation becomes.

The challenge within the Ice Age Floods Study Region is to creatively address three major issues:

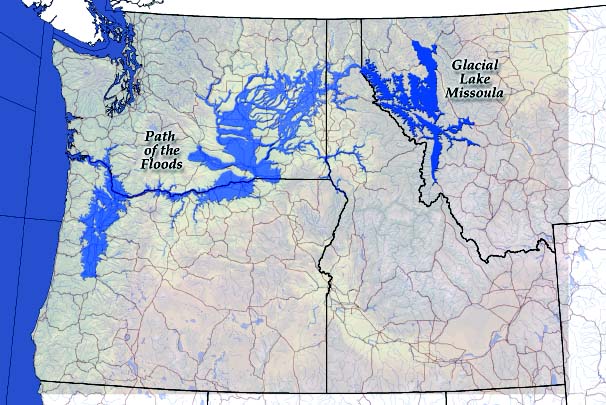

- Identifying Ice Age Floods resources, which are scattered across a four-state area. These specifically include resources related to Glacial Lake Missoula and to the flooding events associated with ice dam failure.

- Developing physical and visual access to specific Floods resources.

- Developing an interpretive framework and program for the natural and cultural history of the Floods region.

|

|

Area impacted by Glacial Lake Missoula and the Floods

|

1. Basic Concept

| |

Tour groups mix with school groups at Dry Falls Interpretive Center to see remarkable remnants of the Ice Age Floods. (Photo: M. Sear/Columbia Basin Herald)

|

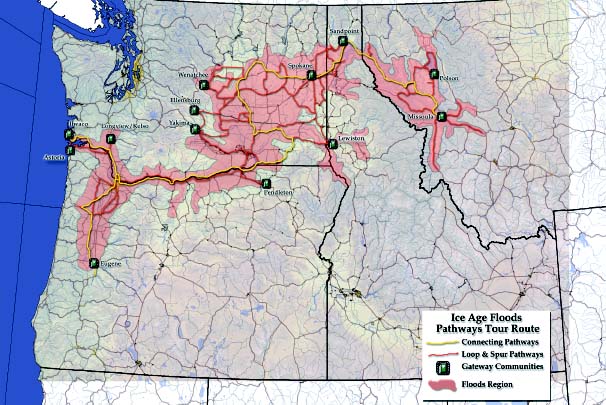

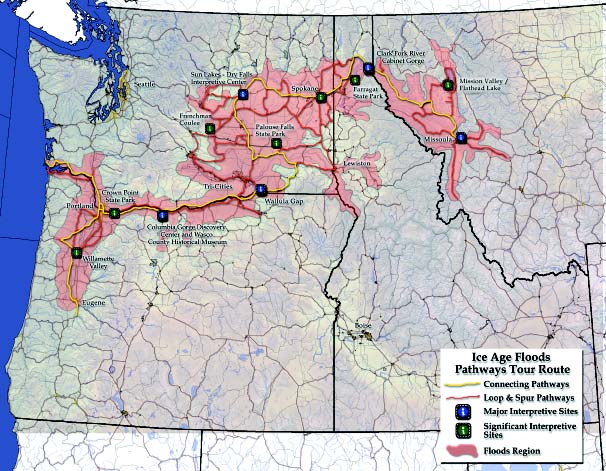

The basic concept developed by the Study Team for interpreting the Floods story is that the study area, which covers a four-state area, be defined as an Ice Ages Floods Geologic Region. Within the Floods Region would be Floods Pathways that follow existing highways. These Floods Pathways would provide visual and physical access to significant Floods features and help link the features as part of a coordinated project.

There are a number of different approaches that can help a visitor understand and appreciate the many and varied aspects of the Ice Age Floods story. Because of the scale of the Floods region, a narrative approach may be the most effective way to develop an understanding of the larger story. This narrative could be in written format or be integrated with a number of multi-media alternatives. The majority of existing Floods features are best experienced in person, either by walking or driving to features, or by flying overhead. Interpretation at specific locations and regionwide could:

- Explain the story of the Floods resources both at specific sites and at regional and other interpretive centers

- Place a site into the context of the larger Floods story

- Explain the geologic background of a site prior to the Floods

- Interpret the cultural history of an area as influenced by the Floods, tying in the dynamic historic story with the geology of each area.

2. Development of a Floods Tour Route Approach

| |

|

|

The Ice Age Floods Created Palouse Falls

Before the great floods, the Palouse River flowed down Washtucna Coulee to join the Columbia River in the Pasco Basin. The huge torrents of the Floods filled and overflowed Washtucna Coulee and swept across the divide down into the adjacent Snake River Valley. This enormous overflow carved back the divide in one place enough to capture the Palouse River, diverting it south to the Snake. The lower 10 miles of the Palouse now flow through a deep spillway. Its last descent is over a 200-foot cliff: Palouse Falls.

|

|

The original planning concept was to develop Floods Tour Routes and to direct visitors to selected Floods features near major Interstates and U.S. Highways. These routes would be defined as being “primary” or “secondary” based upon the type of road and the number of significant Floods features nearby. After discussions with geologists and other Floods experts, it was agreed that this approach was overly simplistic and would not work as originally intended. With the number and variety of Floods resources, it was felt that visitors would gain greater appreciation and understanding if a number of Floods Tour Routes were identified and marked, allowing a greater variety of sites to visit. If time is limited, visitors could choose conveniently located sites along their way. If they have several days, visitors could see a greater number of sites.

This modified planning concept focused on identifying Floods Pathways that would follow U.S. Highways as well as state highways and local roads, but would stay off interstate highways as much as possible. In some instances, non-motorized trails and water trails could link to certain Floods features. There would be no “hierarchy” of routes based upon importance to the Floods story; all would simply be defined as Pathways providing access to significant Floods features. In many ways, this approach is more in keeping with the paths taken by the original floods.

It should be noted that the original concept was described as an interpretive motor tour, but was rapidly expanded to include auto, train, tour boat, airplane, bicycle and even hot air balloon tours.

3. The Process of Determining the Most Effective Tour Route

| |

|

|

Hydraulic Dam

What is a hydraulic dam? It is the restriction of the rate of water flow caused by a narrowed reach in a river valley. During a valley-filling flood, the narrows restrict flow, thus causing water upstream to pond partly and temporarily. The most spectacular example of a hydraulic dam during the Ice Age Floods was Wallula Gap, which restricted nearly 200 cubic miles of water in a huge, temporary pond in Pasco basin. On the lower Columbia, a narrows near Kalama also briefly ponded floodwater. This narrows thus helped to back up floodwater upstream, flooding not only the Portland–Vancouver basin but also the Willamette Valley to beyond Eugene.

|

|

Determining which existing roads and highways would be designated as “Pathways” was based upon two criteria: (1) path of the original flood waters, and (2) the location of significant Floods features, including Glacial Lake Missoula.

The Floods resulted from the release of water impounded in western Montana by ice dams near the mouth of the Clark Fork River. Glacial Lake Missoula extended far upstream from Missoula in several valleys. The lakeshore came within about 15 miles of the contental divide. The volume of water from the Floods was so great that it followed several different channels across the Idaho Panhandle. When the floodwater reached the relatively flat Columbia Basin of eastern Washington, it spread out across three major drainage areas on its way to the Columbia River, Wallula Gap and the Columbia Gorge. At the Gorge, the water was confined to the steep river valley. Farther down the Columbia River, a hydraulic dam was formed at the narrows at Kalama, Washington, and the backwaters flooded south into the Willamette Valley. The Floods continued down the lower Columbia to the ocean, which was 40 miles west of present-day Astoria, Oregon. It was important that Floods Pathways allow a visitor to follow the path of the floodwater from Missoula to the mouth of the Columbia at the Pacific Ocean.

The inventory of the Ice Age Floods resources was used to help determine pathways of the Floods. To date, more than 350 Floods resources have been inventoried, and additional inventories are still being conducted. The four Study Zone Working Groups, after identifying the resource sites, were asked to rank their Floods resource sites whenever possible, and those sites were located on a map of the study area. The intent of the Pathways was to provide access to these sites.

|

|

Floods Pathways, Loops, Spurs, and Gateway Communities

|

4. Recommended Routes of the Pathways

| |

|

|

Well-Traveled Meteorite

The Willamette meteorite is the largest ever found in the United States, weighing 31,107 pounds. It was found in 1902 two miles northwest of West Linn, Oregon, at an elevation of 380 feet above sea level. Apparently, an iceberg carried the meteorite along with granite erratics from either the Cordilleran ice sheet or the Purcell lobe in British Columbia to the Willamette Valley. The meteorite must have been moved with the glacial iceflow to near Lake Pend Oreille and then carried downstream with one of the great Ice Age Floods.

|

|

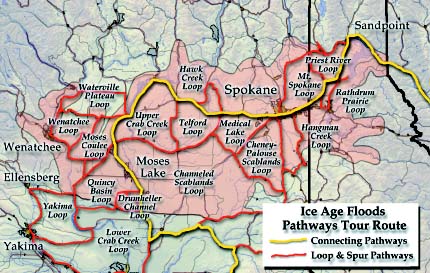

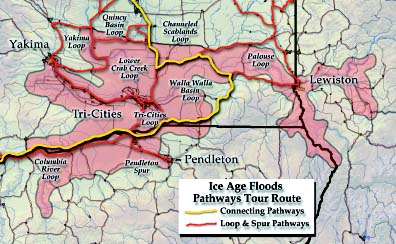

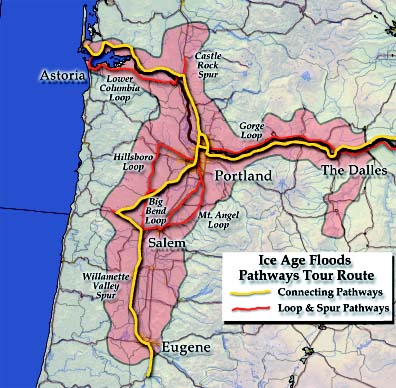

Pathways

An earlier discussion of the development of a tour route approach examined the desirability of using the term “Pathways” over “Primary” and “Secondary” Floods routes. The use of the generic term “Pathways” does not denote a hierarchy of routes, but is intended to indicate to visitors the various alternatives they can take to see Floods resources. These various alternatives include CONNECTING Pathways, LOOP Pathways and SPUR pathways. Wherever appropriate, Floods Pathways should utilize existing designated state and National Scenic Byways. Public agencies should coordinate with state transportation departments on these opportunities. These recommended routes are intended to be conceptual in nature to illustrate the basic approach. More detailed management planning will be needed to determine specifically the location of routes and interpretive facilities once the area is formally designated.

Gateway Communities

Related to the Pathways are “Gateway Communities,” which would be the entry points into the Ice Age Floods region and the network of Flood Pathways. These Gateway Communities to the Floods region are important, because at these points visitors would find out about the interpretive and educational opportunities of the Ice Age Floods region and select portions of the region that might be of interest. Criteria used to identify Gateway Communities should include: (1) proximity to Floods features, (2) significant representative features, (3) accessibility, (4) proximity to the perimeter of the Floods region, (5) connectivity to existing roads, and (6) ability to provide visitor services.

The Study Team identified the following Gateway Communities within or adjacent to the Ice Age Floods Region and the major connecting highway or highways:

- Missoula, Montana—I-90, U.S. Highway 93 and State Route 200

- Polson, Montana—U.S. Highway 93 and State Highways 28 and 35

- Sandpoint, Idaho—U.S. Highway 95 and State Route 200

- Lewiston, Idaho—U.S. Highways 95 and 12

- Spokane, Washington—I-90 and U.S. Highways 2 and 395

- Wenatchee, Washington—U.S. Highway 2

- Ellensburg, Washington—I-90

- Yakima, Washington—I-82, U.S. Highway 12 and State Routes 22 and 24

- Longview/Kelso, Washington—I-5 and State Route 4

- Pendleton, Oregon—I-84 and U.S. Highway 395

- Eugene, Oregon—I-5 and State Route 58

- Astoria, Oregon—U.S. Highways 101 and 30

- Ilwaco, Washington—State Route 100 (near U.S. Highway 101).

Pathway Routes (Connecting and Loop/Spur Pathways)

The routes of the Pathways range from simple to highly complex, especially in the Channeled Scablands of eastern Washington.

| |

|

Tour route in the Glacial Lake Missoula Study Zone

|

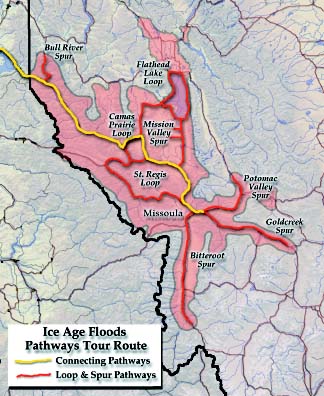

Montana

In Montana the Pathways follow I-90 west from Goldcreek to Missoula on the Goldcreek Spur. The Bitterroot spur runs north from Hamilton via U.S. Highway 93 to Missoula. The Potomac Valley Spur leads from Missoula to Milltown and north on State Route 200 and north on State Route 83 to Salmon Lake. Along these spurs are Floods features that are well-exposed, including wave-cut shorelines on the mountains bordering Missoula.

The Floods Pathways route begins in Missoula and proceeds west on I-90 to State Route 93/200 and north to Ravalli, west on State Route 200 to Route 382 and north Camas Prairie and south on State Route 28 to Plains and west on State Route 200 to the Idaho state line.

The Flathead Lake Loop proceeds from Ravalli on U.S. Highway 93 to Polson and east and north on State Route 35 to State Route 82 near Big Fork. The loop continues west to Somers and south on U.S. Highway 93 to Polson. The Camas Prairie Loop continues south on State Route 28 at Elmo, past Camas and Hot Sprints to Plains, east on State Route 200 to Perma and north on Route 382. The St. Regis Loop begins at Missoula and progresses west on I-90 to St. Regis, north on State Route 135 to State Route 200 and east to Ravalli and south to I-90 and Missoula. The Camas Prairie Loop passes south of Camas. The giant ripples on Camas Prairie were formed by the fast-moving bottom waters of Glacial Lake Missoula during its draining.

Along these spurs, features evidencing Glacial Lake Missoula are well-exposed, including wave-cut shorelines at Missoula and giant ripples at Camas Prairie formed by fast-moving bottom waters of the lake during its draining.

| |

|

Tour route in the Idaho Panhandle and Central Washington Study Zone

|

Idaho

As the ice dam repeatedly failed, flood waters from numerous Glacial Lake Missoulas crashed into the landscape of northern Idaho. The Pathways continue along State Route 200, which is under study as a Scenic Byway by Idaho DOT, to the northern edge of Lake Pend Oreille and Sandpoint. Here the waters flooded west toward Priest River on U.S. Highway 2, southwest along the Purcell Trench on U.S. Highway 95, and mostly south through Lake Pend Oreille and over Farragut State Park. At Rathdrum Prairie, east of Spirit Lake, the Floods created giant ripple marks and left gravel bars and sediments as a record of the Floods passage. The Rathdrum Prairie Loop on State Routes 54 and 53 takes visitors to Post Falls, where the flood waters may have reached speeds of 50 to 60 miles per hour. I-90 from Coeur d’Alene to the Washington State border provides views of landscapes impacted by the Floods.

| |

|

Tour route in the Mid Columbia Study Zone

|

Washington

Floodwaters rushing into Washington flowed down the Spokane River Valley along the current route of I-90. The Mt. Spokane Loop from Priest River and Newport passes Mt. Spokane State Park, which offers superb views back into Idaho and the Spokane Valley. Near Spokane, the waters split, with one arm following the Spokane River to its junction with the Columbia River. The other spills over into the Cheney-Palouse drainage. The Cheney-Palouse can be seen from U.S. Highway 95, which parallels Hangman Creek. The Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, near Cheney, contains significant Floods features. The Cheney-Palouse Scablands Loop follows U.S. Highway 195, county roads to Rosalia and Malden, and State Highway 23 at St. John, then northwest I-90 at Sprague. Here visitors return to Spokane via I-90 or continue northwest to Harrington on State Route 23 and then north to Davenport. U.S. Highway 2, which goes through Davenport from Spokane, defines the Medical Lake Loop. Columbia Plateau Trail State Park also provides opportunities for the public to review Floods features. The Telford Loop, off U.S. Highway 2, follows State Route 28 to Odessa and then north on State Route 21 to Wilbur. This Loop and the Channeled Scablands Loop goes through the heart of the Channeled Scablands, which is dotted with many lakes and scour channels. The Channeled Scablands Loop includes the area generally south of Odessa and contains a maze of flood-related coulees such as Lind, Washtucna and Weber Coulees. State Routes 260, 26 and 21 provide access to much of this area. Each road in the area leads the visitor to another Floods channel or scour area.

To the north of U.S. Highway 2 at Davenport, the Hawk Creek Loop takes visitors to the Columbia River and the mouth of the Spokane River and then back to U.S. Highway 21 east of Creston. Here the Pathways continue along U.S. Highway 2 to Wilbur and State Route 174, which leads to Grand Coulee, Grand Coulee Dam and the Columbia River. The roaring floodwaters enlarged Grand Coulee as they headed southwest to Dry Falls, poured over the eastern coulee wall, and created a maze of channels, buttes and dry cataracts. State Highway 155, built on the floor of the Grand Coulee, is a spectacular drive leading to Coulee City and nearby Dry Falls.

Dry Falls, located on State Route 17, is part of the Sun Lakes-Dry Falls State Park. It is a premier site because of existing facilities and the fact that it is the scene of a major cataract. The section of State Route 17 from Dry Falls to Soap Lake follows the course of the lower Grand Coulee. Closely related to Dry Falls is the area included in the Upper Crab Creek Loop. Immediately west of the Telford Loop, the Upper Crab Creek Loop includes Wilson Creek, which is located on State Route 28 from Soap Lake to Odessa. Wilson Creek was one of the areas originally studied by Bretz. Other significant Floods resources are located within the Upper Crab Creek Loop. To the west of State Route 17 is a complex of three Loop Pathways: Waterville Plateau, Wenatchee, and Moses Coulee Loops. The Waterville Plateau Loop on U.S. Highway 2 west of Coulee City includes the area that would have been the southern terminus of the ice sheet. It contains some gigantic erratics adjacent to the highway. U.S. Highway 2 continues along the Columbia River above Wenatchee where U.S. Highway 97 follows along the east bank of the Columbia to East Wenatchee and into the Moses Coulee Loop. Moses Coulee was carved by the Floods. Continuing east on State Route 28 brings the visitor to Quincy Basin, a remnant of Lake Lewis, and to the Quincy Basin Loop. For visitors wishing to proceed west, State Route 283 intersects with I-90 at George and proceeds past Frenchman Coulee to the Columbia River, Vantage, and Ellensburg. Visitors could continue on State Route 243 to the Drumheller Channels Loop. Along the Lower Crab Creek in the Columbia National Wildlife Refuge lies a marvelous collection of butte and basin Floods remnants. After viewing this area, visitors could proceed north to Moses Lake and I-90, or go south on State Route 17.

Continuing south on State Route 17 to State Route 260, visitors encounter two Loop Pathways, the Walla Walla Basin and Palouse Falls Loop. The two can be combined into one rather large loop that leads to Lewiston, Idaho, and back along U.S. Highway 12 past Walla Walla. Just off U.S. Highway 12 on State Route 261 is Palouse Falls State Park, a dramatic Ice Age Floods creation. All the roads into the general areas lead to the Tri-Cities, which lie near the confluence of the Snake, Columbia, and Yakima Rivers. The Yakima Valley Loop goes from Ellensburg on I-82 and leads past Yakima where State Route 24 leads to the western edge of the Lower Crab Creek Loop. The Tri-Cities Loop follows U.S. Highway 730 to Wallula Gap, a narrow constriction of the Columbia River that caused the waters to temporarily back up and create Lake Lewis. In basins created by Lake Lewis are excellent examples of rhythmites and other depositions, as well as erosional features related to the Floods.

| |

|

Tour route in the Gorge, Lower Columbia, and the Willamette Study Zone

|

Washington and Oregon

Beyond Wallula Gap, Floods waters inundated the Umatilla and Dalles Basins, creating Lake Condon. Along this part of the Columbia River, two highways parallel the riverI-84 on the south bank and Washington’s State Route 14 on the north bank. Together, these two routes form the Columbia River Loop. The Pendleton Spur of I-84 leads to the Columbia River at Umatilla. Between here and The Dalles, State Route 14 provides visitors outstanding views of the river and the effects of the Floods. Visitors could cross onto I-84 and the Historic Columbia River Highway to Crown Point. Crown Point is 700 feet above the river level and was topped by floodwaters during the Ice Age Floods. State Highway 14 and I-84 form the Gorge Loop, which runs from The Dalles to Portland. North of Portland on I-5, the Pathways continue to the Kelso/Longview area. The Castle Rock Spur connects Castle Rock and the Kelso/Longview area. The Pathway turns west on Washington State Route 4 on the north bank of the Columbia to Megler near the meeting of the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. U.S. Highway 30 leads from Portland to Astoria along the south bank of the Columbia River, forming the Lower Columbia Loop.

Oregon

Just to the west of Crown Point is the Portland-Vancouver Basin. A hydraulic dam at Kalama Gap forced flood waters to back up into the Willamette Valley and swirl around the landscape near Portland. Interstates I-84, I-205, and I-5, U.S. Highways 26 and 30, and State Route 99-W and 99-E all lead to Floods resources in the Portland area. The Hillsboro Loop leaves Portland on U.S. Highway 26 to State Route 47 and south to State Route 99-W. Following State Routes 213 and 214 will lead visitors to the Mt. Angel Loop. The Big Bend Loop leads visitors southwest of Portland on 99-W to State Route 22 west of Salem. South of Portland, I-5 and State Routes 99-W, 99-E. 18, 22, 34, 228, and 126 lead to Flood resources in the Willamette Valley as far south as Eugene. The Willamette Valley spur runs from Salem to Eugene.

5. Interpretive/Educational Potential of Recommended Route

Under the mandate of PL 105-391, the “interpretive and educational potential” should be considered when examining an area. There are a few existing interpretive signs and facilities along the Floods Pathways that are oriented to a specific location but they do not provide a coordinated interpretive approach of the Floods. Tying existing interpretive sites into a more cohesive system will help visitors understand the links among individual Floods features.

Interpretive/Educational Materials

| |

States have interpretive highway signs about the Floods, but there is no standardized format for easy recognition. (Photo: Curtis Archer)

|

There is no single “best” interpretive tool; some approaches and tools work better at specific locations than others. Interpretation is the key that ties all the Floods resources within the Ice Age Floods Region together. Many of these interpretive methods can provide employment for local subject matter experts and together with the sales of interpretive materials add to the economic base of the local area. By tying interpretation into local museums, existing visitor centers, and Chamber of Commerce offices, additional information on the cultural heritage of specific areas can be distributed. A list of potential interpretive methods could include:

- Printed tour guides for visitors.

- Wayside exhibits near specific Ice Age Floods resources.

- Interpretive centers for orientation and interpretation, which would be developed at critical locations across the four-state area.

- Videos of the Ice Age Floods story to be shown at visitor centers, and sold to the public.

- Books on the Ice Age Floods, which should be written at various levels and in various languages.

- Pamphlets covering specific geographic areas or subjects.

- Computer games that include aspects of the Floods story.

- Multi-media applications to stimulate interest in the Ice Age Floods story. These could be sent out in advance to individuals or groups prior to their visit to the Floods Region.

- Audio car and TV tapes to describe what Flood resources the visitor is seeing.

| |

On the Waterville Plateau, house-sized boulders were transported great distances by the glaciers. (NPS Photo)

|

- Travel maps covering the Ice Age Floods and specific areas.

- On-line resources.

- Personal tours and guided trips for visitors to the Floods Region.

- Exhibits to be shipped to local museums and visitor centers in or near the region.

- Special study group programs, such as Elderhostel or summer schools for all generations.

- School programs in the region to promote involvement in preserving Floods resources.

- Interpretive centers at hydroelectric dams.

Interpretive Efforts Within the Area

The area covered by the Ice Age Floods Region has many sites, parks and areas in which interpretation emphasizing other themes is already taking place. A sampling of these areas includes:

- Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail—MT, ID and WA

- Oregon National Historic Trail—OR and WA

- Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area, WA

- U.S. Forest Service Interpretive Centers, National Forests in MT, ID, OR, and WA

- Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, USFS—OR and WA

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Refuges—WA and OR

- Tribal Cultural Centers—MT, ID, OR and WA

- Historic Columbia River Highway Scenic Byway—OR

- Heritage Corridors Program—WA

- State Parks—MT, ID, OR, and WA

- Scenic Byways Program—ID, OR, and WA

- County Museums and Historical Societies—MT, ID, OR, and WA

- Visitor Information Centers and Chamber of Commerce Offices—MT, ID, OR, and WA

- Privately-owned museums—MT, ID, OR, and WA

- Montana Natural History Center, MT

- Mirabeau Point, WA

- Maryhill Museum, WA

- North Central Washington Museum, WA

- Columbia River Exhibition of History, Science and Technology (CREHST), WA

These facilities and routes provide an opportunity to interpret the Ice Age Floods within existing programs or for expansion to include the Floods story.

Interpretive overlays from various sources enrich visitors’ experiences and can provide unexpected pleasures. The various organizations involved with the Floods story offer a rich tapestry of natural and cultural interpretation that can only be strengthened by cooperation.

6. Interpretive Media Prescription/Alternatives

| |

|

|

Landslides in the Gorge—Not A Result of the Ice Age Floods

The Ice Age Flood ran down the generally “U”-shaped, steep-walled Columbia Gorge without greatly changing it. Landslides occasionally descended into the gorge both before and after the great floods. The largest is the Bonneville Landslide about 500 years ago. Nearly 14 square miles of material slid into the Columbia River creating a temporary dam and lake that rose to an elevation of 277 feet. This event has been remembered in local Native American legends as the origin of the “Bridge of the Gods.” Lewis and Clark identified this strange topography as a landslide and stated that it caused the dangerous rapids they called the “Cascades of the Columbia.”

|

|

There are several types of interpretive methods that could be used to tell the story of the Ice Age Floods and the cultural history of the Ice Age Floods region.

- On-Site Interpretation—For many Floods resources, the most effective way to provide interpretation is to do so on site. If, for example, interpretive material is addressing gravel bars, the interpretive site should be located near the feature. If a visitor can actually touch a Floods resource without damaging it, the better the potential interpretive impact will be. Because of the large scale of Floods resources such as ripple marks and gravel bars, a view from farther away can enable the visitor to appreciate the feature better: In certain situations, if visitors stood on top of a ripple mark, they might not be able to recognize the feature. Future planning will address exactly where various interpretive facilities or overlooks should be located. For example, one question would be “Is it better to interpret the Floods related glacial lakes from the floor of the valley, or should the interpretive site be located on the the lake’s shoreline 800 feet above the valley floor?”

- Orientation and Interpretation—There are two components of the proposed interpretive program for the Ice Age Floods Region: (1) Orientation, and (2) Interpretation. When visitors first arrive in the Ice Age Floods region, they will want to know what educational opportunities are available, and where various interpretive sites are located. This process is typically referred to as “Orientation.” Orientation can be provided to potential visitors in a number of ways. One approach would be to use audio-visual techniques that can be sent to interested individuals, or made available in the Gateway Communities that lead into the Floods region. Orientation can also continue throughout the region by using road signs, tour guides, pamphlets, interpretive signage, and tour maps to help direct visitors. Websites can be used to reach a broad audience.

The second component of the proposed interpretive program is the actual interpretation process. Freeman Tilden, in his Interpreting Our Heritage, stressed the point that “Information, as such, is not Interpretation. Interpretation is revelation based on information. But they are entirely different things.” Interpretation would occur through printed tour guides, wayside exhibits, museum exhibits, pamphlets, maps emphasizing specific aspects of the Floods, personal tours, and guided trips that focus on the Floods. All of the information can, according to Tilden, lead to a “revelation” for the visitor.

Floods features around Flathead Lake (Montana) are already being interpreted through a series of boat tours. The boat captain of a local tour company has included Floods features as part of a tour around the lake. In many ways, this is one of the better methods to see Floods features because the leisurely speed of the boat allows enough time for a quality interpretive experience. Chartered planes can provide the best views for areas such as the Channeled Scablands.

The development of interpretative waysides along Floods Pathways could be tied into each of the four states’ Departments of Transportation (DOT). The various state DOT’s could administer the Highway Heritage Marking and Scenic Byway programs as part of partnership programs.

Making interpretive materials available for visitors to take home with them when their trip is completed can reinforce interpretation. Books, audio and video tapes, computer games, and inexpensive items such as postcards can all provide reinforcement of the visitor’s experience.

- Education—To many people, the term “education” is similar in concept to interpretation. In this study, however, “education” refers to educating the public about the Ice Age Floods region and Pathways in an effort to engender a sense of protection and “possessory” interest. One way this could be accomplished is through public presentations in the cities and towns included in and surrounded by the Ice Age Floods region. Using the concept of cooperative management and responsibility, it is important that residents understand and support the goals and objectives of the Floods region. Partnerships at the state and local levels would have to be built and maintained through the education process. This process would be ongoing as new residents move into the area and as new leaders develop and mature.

The Ice Age Floods Institute can play a significant role in education and by providing additional opportunities in outreach programs and grant writing.

One specific area that has great promise for the Institute is working with local school districts to incorporate the story of the Floods in earth science curricula. College and post-graduate studies and research would also be encouraged.

- Tourism and Economic Benefits—The educational and recreational benefits of developing the Floods region and Pathways have been explained, but there is also a component of interpretation that is related to economics. Providing quality interpretive recreational travel opportunities for visitors to the region has a direct relationship to the length of visitors’ stays and to the lodging, food service, and other facilities they require. Additionally, the production of interpretive materials is a potential source of revenue for local entrepreneurs. With increased visitation to the region, additional interpretive and tourism-oriented opportunities become economically viable. The Channeled Scablands can best be seen and comprehended from the air; this characteristic could lead to an increase in scenic flights in small planes or hot-air balloons. At the present time, there are no interpretive boat trips through Wallula Gap, but the potential for developing such a service would be enhanced with the proposed Floods region. As seen in places such as Scotland and Ireland, the profusion of bed and breakfast accommodations would be expected to increase in direct proportion to an increase in visitation. There are adequate accommodations within the Floods region at the present time. An increase in the number of visitors would provide expanding opportunities for the hospitality industry.

7. Coordinated Interpretive Program

| |

Ice Age Floods resources are evident all along the pathways of the floods and allow the visitor to obtain a vivid understanding of the power of the floods. (Photo: M. Sear/Columbia Basin Herald)

|

At the present time, there is no coordinated interpretive program for the Floods at the federal, state, and local levels. Among the responsibilities of a project or public agency support staff would be coordinating interpretation throughout the Ice Age Floods region. The goals would be to: 1) develop standards for directing visitors to the various Floods resource sites; 2) identify similar interpretive approaches at these sites; 3) recommend improvements to existing interpretive efforts; and 4) work with local museums and visitor centers to encourage participation in the region’s interpretive efforts. Within the past year the Port of Walla Walla has started preliminary planning, with help from the Ice Age Floods Institute, for a large wayside exhibit near Wallula Gap. Avista, a northwest power company, has shown interest in expanding and improving the interpretation at its hydro sites. More than 60 scientists and educators gathered in the Channeled Scablands to study Floods resources in the area. In addition, the Idaho Department of Transportation is studying State Highway 200 for “scenic byway” status.

In Washington State the Washington State Department of Transportation, in partnership with other state and federal agencies, including the Washington State Arts Commission, the Department of Community, Trade and Economic Development, the Interagency Committee on Outdoor Recreation, the Department of Natural Resources, the State Parks and Recreation Commission, the Washington Commission for the Humanities, Bureau of Land Management, and the NPS, are supporting an effort to promote cultural tourism along approximately 100 miles between Othello and Grand Coulee Dam, along State Routes 17 and 155 in central Washington.

Intertwining canyon networks were cut by the Ice Age Floods. (NPS Photo)

|

Such efforts point to the recognized need for coordination to help standardize the production of interpretive material and to provide technical assistance.

Signage

Perhaps the most basic way to help visitors appreciate the Floods story is through a coordinated system of signage that can both convey information and help with orientation. Such a signage system is essential because of the size and complexity of the Floods region. For visitors to fully understand the story of the Floods and the impact the Floods had upon the land, they need to experience individual Floods features. In addition, they need to understand how all of these features were formed and how each is a piece of a much larger puzzle.

Across the region there are few interpretive signs that refer to the Floods. Most of those that exist are very informative and tell a part of the Floods story.

When visitors are traveling through the Floods region, they need to be able to follow easily a particular Floods Pathway and to identify and locate individual Floods features. Signage for the Floods region could be implemented a number of ways: 1) incorporating a Floods logo and/or title on existing or future signs, 2) developing a small sign that could be attached to existing or future signs, or 3) developing new standard signs that could be used along highways to identify Pathways as well as specific Floods features. In all instances, signing would be coordinated with state transportation departments.

| |

The great floods left a lasting mark on the landscape. (NPS Photo)

|

Each sign should include a name, such as “Ice Age Floods Geologic Trail,” and a logo that needs to be developed. This logo could visually include concepts relating to the Ice Age, formation of the ice dam and the resulting Glacial Lake Missoula, the power and force of the Floods once the water was released, the extent of the Floods region, or the impact the Floods have had on the land.

For the Floods Pathways, which follow existing highways, each sign should also include the name of the loop, or spur. These signs could be color coded for ease in following a specific loop.

| |

Giant ripple marks at Camas Prairie, Montana (NPS Photo)

|

Signage can also be used to help visitors get a better understanding of what they are seeing. For example, visitors entering the Channeled Scablands could be greeted with signage and interpretive literature that says “Entering the Ice Age Floods Geologic Region” or something to the effect that “You are about to enter an unusual geologic landscape similar to that on the Planet Mars.”

Each community and organization would still have the opportunity to develop its own signage. The more these types of signs relate to the Floods region, the easier it will be for visitors to understand the larger story of the Floods.

| |

Flood waters unable to flow through the Wallula Gap backed up to a height that overflowed the bluffs to the right. (NPS Photo)

|

8. Development and Enhancement of Interpretive Facilities

One of the tasks of the Floods Study Team was to determine if any new facilities would be needed to help interpret the Floods story, or if any facilities needed renovating or expanding. In the planning discussions with the Study Team, five major interpretive center locations were identified. Three of these would be new facilities while two would require the renovation of existing facilities.

| |

Crown Point, located at the western portal of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, was topped by Flood water some 700 feet deep. (NPS Photo)

|

Major Interpretive Sites

- Missoula, Montana—(to be developed). Beginning in western Montana, the source of the Floods waters, there is a need to construct an interpretive facility to provide orientation to the Ice Age Floods region and to interpret Glacial Lake Missoula. The principal features of this site are the wave-cut shorelines marking lake levels of Glacial Lake Missoula far above today’s valley floor. Such an interpretive center could stand alone or be constructed in cooperation with an existing site. The local, state and federal government officials in the area are interested in developing partnerships with interested agencies and the private sector to develop an Ice Age Floods Visitor Center.

- Clark Fork River/Cabinet Gorge, Idaho—(to be developed). The area around Cabinet Gorge and the mouth of the Clark Fork River is a key geologic and interpretive area because it is the location of the ice dam that created Glacial Lake Missoula. Future planning should focus on the location of a major interpretive and orientation facility and supporting services. This would tie into current planning being done to designate Idaho State Route 200 as a scenic byway.

| |

Grand Coulee, upper center, channeled the flood waters to Dry Falls, 20 miles south. Today, the Columbia Basin Irrigation District pumps water into Grand Coulee to support a vast irrigation system. (NPS Photo)

|

- Sun Lakes-Dry Falls Interpretive Center, Washington—(expand existing site). The J Harlen Bretz Visitor Center at Sun Lakes-Dry Falls Interpretive Center has 63,059 visitors a year (1999 figures). The limited program uses a relatively small facility that is often overloaded during the height of the visitor season. Sun Lakes-Dry Falls Interpretive Center is a premier Floods interpretive site and is near the core of the Floods resources in the central Washington area. Working with the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission, local communities, and the National Park Service, future planners could determine the most appropriate manner of expanding the facility and services. The Washington State Department of Transportation is currently working with local citizens to develop a Corridor Management Plan for State Highway 17, which passes by Dry Falls. Among other items, the Corridor Management Plan will cover opportunities for increasing the number of wayside exhibits and other interpretation.

| |

Orientation is the essential first element of interpretation. Here Richard Waitt diagrams the course of the Floods at Dry Falls. (Photo: M. Sear/Columbia Basin Herald)

|

- Wallula Gap, Washington—(to be developed). Wallula Gap is a significant and highly visible Floods resource. The Port of Walla Walla is planning an interpretive wayside area just to the north of the Gap on U.S. Highway 12 that will include the Floods story. The next step is to secure funding for construction and operation of the visitor facility. If this area is not suitable for future expansion, the local community and future planners could determine where an interpretive facility could be located to provide orientation and interpretation. In any case, some interpretive facility covering the Floods should be located at the Gap to tie the interpretation directly to the resource.

- Columbia Gorge Discovery Center and Wasco County Historical Museum, The Dalles, Oregon—(expand exhibits at existing site). The Discovery Center currently interprets the Ice Age Floods and their impact on the Gorge. The area around The Dalles has a number of significant Floods resources that are easy to see and visit. With the anticipated increase in the number of Floods-related visits, more exhibit space will be needed for greater in-depth interpretation and orientation.

One grasps Bretz’s evidence most firmly by viewing it in the field... .

Richard Waitt, USGS

|

|

Ice Age Floods major interpretive sites, Floods Pathways, Loops, Spurs, and other significant interpretive sites.

|

9. Other Significant Interpretive Sites

In addition to the five Major Interpretive Sites, the Study Team identified other examples of sites where the Floods story could be told. Other existing interpretive facilities such as local visitor information centers, museums, and cultural centers will also be impacted by the increased visitation to the region and could be identified as sources of Floods information. Partnerships with these local interpretive facilities should be developed to enhance the present level of interpretation and to assist the facilities in developing additional interpretive materials. Emphasis should be on the utilization of existing facilities where possible.

| |

A huge haystack rock, transported by a glacier, 10 miles west of Sims Corner, Washington (NPS Photo)

|

Some of the significant areas for interpreting the Floods story include:

- Mission Valley/Flathead Lake, Montana—(to be developed). The Mission Valley contains several Floods features, including Markle Pass, Camas Prairie and strandlines from Glacial Lake Missoula. Flathead Lake is possibly a remnant of Glacial Lake Missoula and one of the last remaining glacial lakes in the lower 48 states. These are great places to view Floods resources.

- Farragut State Park, Idaho—(expand existing site). Farragut State Park on the south end of Lake Pend Oreille is where the flood waters burst out from the broken ice dam. A small display is planned for the visitor center, and there is a wayside exhibit near the lake. With an increased interest in the Floods, the park may find the demand for additional interpretation will overwhelm current facilities. Avista, a regional power company, is planning to upgrade the interpretation at all of its hydroelectric facilities, including Cabinet Gorge at the mouth of the Clark Fork River. The Study Team is assisting planners at Avista with their interpretive efforts.

- Spokane Area, Washington—(to be developed). The Spokane area is an ideal site for locating an orientation and interpretive facility in conjunction with I-90 and other U.S. highway routes entering the area. At the present time, there is no such facility in the vicinity of Spokane. There has been no discussion with the local or state officials regarding the location of a visitor center, but with the increased interest in and the economic potential from the Ice Age Floods region, the opportunity becomes more attractive. There is a Floods interpretive sign in Riverside State Park in Spokane.

- Frenchman Coulee, Washington—(to be developed). Frenchman Coulee is very close to I-90 and can be reached by taking Exit 143. It was formed as flood water drained from Grand Coulee and the Quincy Basin. The water dropped 500 feet in a series of huge waterfalls to the Columbia River. This site is an ideal area to interpret or introduce the Ice Age Floods and is in relatively pristine condition.

| |

|

|

Snake River Flowed Backwards

The Ice Age Flood waters surged across the Channeled Scablands, across the Palouse, and into the Snake River with such a discharge the river was backflooded 80 miles east to beyond present Lewiston, Idaho. On the banks of the Snake River south of Lewiston, a gravel bar laid down by the single Ice Age Bonneville Flood is overlaid with flood sands from several Ice Age Missoula Floods.

|

|

Also of interpretive value are resources located at Ginkgo Petrified Forest State Park across the Columbia River at Vantage, Washington.

- Palouse Falls State Park, Washington—(expand existing site). Sixteen miles south of Washtucna, the Palouse River drops 198 feet into a gorge six miles north of the Snake River. The Palouse River that flowed down the Washtucna Coulee was diverted south by the Ice Age Floods. Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission maintains a modest park here with Floods interpretation.

- Crown Point State Park, Corbett, Oregon—(enhance existing site). Crown Point State Park at the west entrance to the Columbia Gorge stands at 700 feet above the river and is an interesting Floods landmark. It was inundated during the time of the peak floods. An adjacent area, Portland Women’s Forum State Park Scenic Viewpoint, overlooks Crown Point and could be considered for enhanced exhibits to handle the increased visitation and provide an outstanding interpretive experience.

- Willamette Valley, Oregon(to be developed). At the present time, there is no facility in the greater Portland area and Willamette Valley to interpret the Ice Age Floods and their impact on the Valley. The I-5 corridor is heavily traveled and there is a need for an orientation/interpretive facility in this area. By working with the local communities, future planners could determine the best location for such a facility.

There are a number of other opportunities to locate additional interpretive facilities or upgrade existing facilities to accommodate the visitors to the Ice Age Floods region. The Study Zone Working Groups can survey their respective areas and discuss the interpretive opportunities with the local communities. For example, within the Channeled Scablands of east-central Washington, the communities of Grand Coulee, Odessa, Moses Lake, and Othello are expected to have increased visitation with the designation of the Ice Age Floods region. These communities already provide visitor services in a remote and rural area, and will need technical and financial assistance to enhance and expand current interpretive facilities. Other communities within the Ice Age Floods region could, over the years, demonstrate needs for interpretive facilities and join in partnership programs with Ice Age Floods managers to enhance the visitor experience.