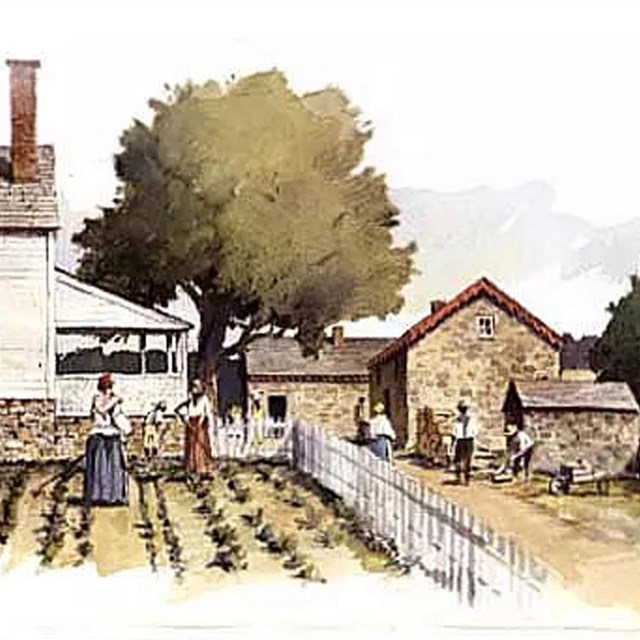

NPS/Tim Ervin African Americans hosted their own religious services in the woods at Hampton and attended religious meetings with neighboring groups of free Blacks and enslaved persons. One laborer, Nick Toogood (1786-1879), was said to be a “spiritual leader” among the enslaved at Hampton and was known as a powerful hymn-singer. There is documentary evidence of burial grounds for the enslaved and later free Blacks on the original Ridgely properties, though the location of these sites remains unrecorded.

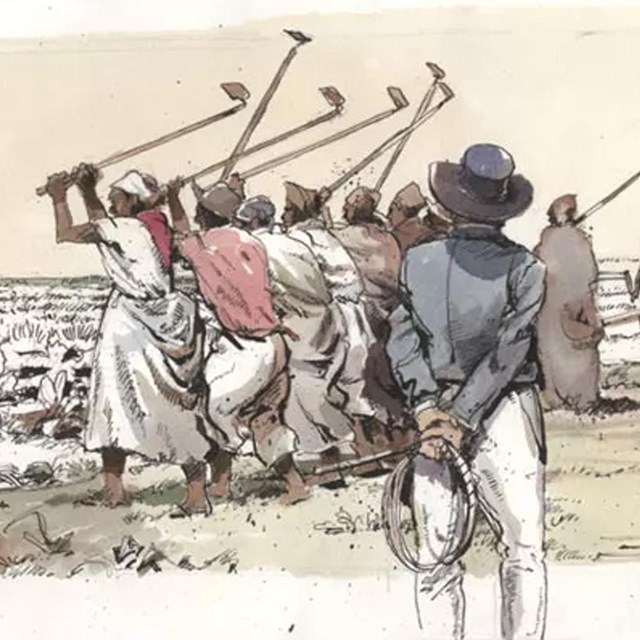

NPS The Ridgelys also had their own ways of promoting Christianity among Hampton’s enslaved community. Eliza Ridgely provided church services in the attic of the Hampton carriage house, under the direction of a white minister, Rev. Galbraith. She also held community gatherings, centered on weddings and funerals, in the great hall of the mansion. Her daughter Eliza, or “Didy,” recorded in her 1853 journal that she taught enslaved children Sunday School classes, which included learning the Lord’s Prayer and memorizing Bible verses. For the Ridgelys, as well as other enslavers, setting the guidelines for religious practice seemed to mean that they shared a common humanity with enslaved persons, while also providing social control and demands for enslaved persons to take on their beliefs and behavior. For the enslaved, lessons of a shared religion gave them a language with which to compel the enslavers to behave as Christians and allow them to seek knowledge, both Biblical and otherwise. During the Civil War, Ridgely family member Henry White recalled that enslaved children approached him for to learn to read (then not permitted) so that they could better prepare for the freedom they hoped was coming:

Enslavers’ attempts to provide Biblical instruction and institutionalize Christianity among the enslaved was, like so many other aspects of American slavery, a process of struggle and negotiation.

Learn More

|

Last updated: March 26, 2024