NPS photo. A great diversity of wildlife lives in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Endangered bats flutter through forests at night, and at dusk elk roam through the remote Cataloochee valley. If you're lucky, you might glimpse a bear taking a nap on a tree branch, or an otter slipping into a shady pool. From the streams to the skies, animals here have one thing in common: their well-being depends on good management by the park's wildlife management team. What is wildlife management? Ever since the early years of the national park in the 1930s, rangers have been responsible for the health of wildlife within its boundaries. For many years, though, there weren't separate resource management rangers, education rangers, and law enforcement rangers-there were just "park rangers," and these people did it all. Gradually, as park visitation increased, rangers who dealt with wildlife became more specialized: they studied biology and wildlife management in college and graduate school, and became experts in their field. Today, many of the Smokies' wildlife managers have dedicated their lives to keeping the Smokies' animals healthy and wild. While there are only three permanent, year-round wildlife managers, an additional 4-5 people plus 6 interns come on board during the busiest months: January-August. Managers work long hours, often in the backcountry, searching for invasive hogs, monitoring elk and bear populations, fixing broken cable systems for hanging backpackers' food, mapping habitat for endangered species, and much more.

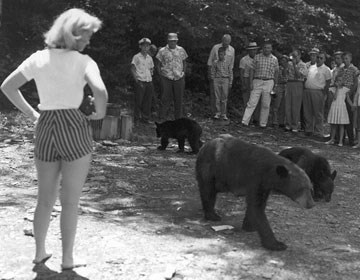

NPS photo. Managing Bears A main attraction for visitors to Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the chance to see one of our approximately 1,500 black bears (Ursus americanus), and a main responsibility of wildlife managers is to monitor those black bears over time. Each year, NPS wildlife managers and researchers from the University of Tennessee have monitored the bears using several different techniques: bait-stations, hair traps (barbed wire that catches strands of bear hair as the animals rub against it), and mark-and-recapture (when bears are caught, weighed, marked, released, and then often caught again to go through the same process in subsequent years). The University of Tennessee is not, at this point, conducting hair traps or mark/recapture work, because of low funding. Biologists’ goals are to determine changes in density (number of bears per square mile) and distribution (where bears live in the Park), as well as the composition of the bear population: how many adult, young, female, and male bears there are compared to previous years. They also monitor the food sources for bears, so they can learn how changes in fall food supply affect black bear populations over time. They monitor the food by estimating how much "mast" there is. "Hard mast" includes available tree nuts such as acorns and "soft mast" includes grapes, berries, and other fruits. All of these study methods help biologists assess current bear health, and to know whether management programs are keeping the bear population stable.

NPS photo. Park partners are also invaluable in helping wildlife managers understand bear populations and keep individual bears healthy. The University of Tennessee's long-term bear research, headed originally by Dr. Pelton and now by Dr. van Manen, has provided key population information since 1968. The Appalachian Bear Rescue takes in very young, sick, orphaned, or injured black bears and rehabilitates them for release into the wild-many bears that would not have survived are now living happily again in the Smokies thanks to their efforts. Return to Meet the Managers: Wildlife where you can find the NPS profile: Keeping our bears wild, and the Partner profile: Bears over the long-term.

NPS photo. Managing Deer White-tailed deer live throughout Great Smoky Mountains; however, most are found in the Cades Cove area. When the Smokies first became a Park, rangers noted very low numbers in Cades Cove, perhaps due to over-hunting. However, the deer population there spiked in 1970s and 80s, then gradually declined during the 1990s and 2000s, mostly likely due to an increase in predators such as bears and coyotes. The population is now at a stable and healthy level. Visitors can spot deer all over the Park, but are almost sure to see their ears pricked above the tall grasses of Cades Cove or in the open areas of Cataloochee, Oconaluftee and Sugarlands. Wildlife managers monitor the population and health of the deer herd in Cades Cove. Maintenance employees, vegetation managers, and fire managers also coordinate their activities carefully with wildlife managers to ensure a safe habitat for deer. One of the biggest threats to deer in the Park comes from visitors feeding them. Deer, like bears, become food conditioned (trained) and seek out humans to beg for treats. Not only does this make them more likely to stand in roads and risk being hit, the food itself is very unhealthy for deer. In fact, one food conditioned deer that wildlife managers collected as part of a herd health check had an extremely high parasite count in its abomasum (the deer’s fourth stomach compartment). Another threat to deer comes during their fawning season—late May through mid-July—when young animals are immobile. While native predators such as bear and coyote search the grasslands and do eat some fawns, wildlife managers are most concerned about threats from people. Within the Park, managers work with maintenance staff and vegetation managers to restrict mowing, tractor use, and other disturbances in the tall grasses. But they can’t stop many visitors from rescuing “abandoned” fawns. When a female deer feeds, she often leaves her fawn alone in a grass bed to nap in the warm sun. Some visitors find a fawn alone and, without observing it very long, assume that this deer is an orphan, pick it up, and bring it to rangers. Rangers do not always know where the fawn came from in the wide expanse of grass, so they don’t know where to put it so its mother will find it again. Moving fawns—even ones that seem abandoned—can be fatal to the fawn, and disturbing wildlife is illegal. What should you do instead of moving a fawn? If the fawn is simply alone, leave it alone. It’s very likely that the fawn’s mother is nearby, probably watching and waiting for you to go. If the fawn appears sick or injured, either remember the location or leave a member of your party at a good distance from the site, and contact a ranger. They have the equipment and veterinary support to help sick or injured animals.

NPS photo. Managing Elk Elk used to roam the meadows and forests of the Smokies and the entire southeastern United States, but they couldn’t survive large-scale habitat loss and over-hunting. The last wild elk in North Carolina died in the late-1700s, and in Tennessee in the mid-1800s. Wildlife managers knew that elk play an important role in grazing grasslands and in the food chain, so reintroduced 25 animals in 2001 and 27 more in 2002 into Cataloochee, the far southeastern portion of the Park in North Carolina. To read a more complete description of elk history and elk facts, visit the Park’s elk information page. Click the “back” button to return to this page. The Smokies’ new elk herd did not flourish at first. Calves were dying at an alarming rate. Wildlife managers discovered that black bears—a normal predator of elk calves, but not one which usually devastates a population—were killing calves. To help the elk population grow, wildlife managers tried an experimental bear-relocation program. For 3 years, managers captured black bears and dropped them off at a site in the Park about 40 miles from Cataloochee. Their goal was not to eliminate bears from the Cataloochee area, because keeping both predators and prey in a habitat is important, but rather to give the elk calves a chance to grow big enough to defend themselves. Managers knew from their work with nuisance bears that most of the relocated bears would make their way back to Cataloochee, although by the time they did, the calves would be big enough to avoid the bears.

NPS photo. Moving bears worked, managers concluded, after three years of successfully reared elk calves. Enough elk calves survived that the population appears secure. Managers also noticed something surprising: the adult cows seemed to be learning how to be better mothers in the presence of bears. They gave birth to calves in more protected areas, and when bears did threaten them, they had learned to fight back. Moving bears was no longer necessary. Today the elk population has grown to an estimated 90 animals. In addition to thriving at Cataloochee, the elk roam as far as Oconoluftee in the south-central area of the Park. Wildlife managers in Cataloochee, including Joe Yarkovich, constantly monitor the elk. Most elk wear a radio collar so managers can locate them for routine checkups and to monitor their daily movement patterns. In the future, the only animals you’ll see with collars will be cows. In the early summer the elk give birth to calves, and in the fall their unearthly bugles echo through the quiet forests. Interns often help wildlife managers study the elk herd.

NPS photo. Endangered Species We’re lucky that the Endangered Indiana Bat calls the Great Smoky Mountains home. In fact, the Park has the largest colony of winter hibernating Indiana Bats (Myotis sodalis) in Tennessee. The Indiana Bat’s summer habitat includes forests of the Great Smoky Mountains and surrounding National Forests. Specifically, bats look for trees with dead and dying trees with loose bark and lots of solar exposure. They take advantage of habitat that’s available on the landscape, such as pine trees that have succumbed to the southern pine beetle. Outside these protected areas, development such as new building, land clearing, logging, and mountain-top removal destroy the bat’s habitat. In 2008-2009, wildlife managers received grants from the Tallassee Fund, the National Park Service Fire Management Program Center in Boise, and the National Park Foundation to study roost (bat “bedroom”) ecology of the Indiana Bat in the Park, and in the Cherokee and Nantahala National Forests that surround it. An additional grant from the Joint Fire Science Program extends this research for 3 years. The studies are especially concerned about protecting critical summer roost habitat because bat populations are slow to recover from disturbances. While adult bats rely on some disturbances, such as fires during plant growing seasons, uncontrolled burns can kill baby bats. Understanding habitat needs of bats at all life stages is critical for developing effective forest management practices such as prescribed fire. All of these studies come at a time when bat populations are being devastated by White-nose syndrome, so understanding habitat use to protect it is a priority. Wildlife managers are also responsible for the endangered Carolina northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus) and the Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis), as well as their habitat. The Smokies are also home to many Species of Concern. Check the complete list of threatened and endangered species then use the back arrow to return to this page.

NPS photo. Non-Native Animals

NPS photo. Hogs are the most worrisome of these non-native species. Hogs root out native plants and destroy streambanks (and with them, habitat for salamanders, trout, and other sensitive wildlife). They can also carry disease, including swine brucellosis, pseudorabies, and hog cholera (classic swine fever). Pseudorabies, also called “the mad itch,” is not rabies, but rather a form of herpes similar to chicken pox in people. Just like chicken pox, it’s highly contagious. To wild canines, including our coyotes and foxes, the disease is fatal, so wildlife managers want to ensure that they eliminate as many hogs as possible. In addition to carrying disease, hogs are like huge plows: they root under the soil looking for food, and destroy large areas of forest and field habitat. Hogs are not native. The hogs you might come across in the Smokies today are from two main sources. The first source has resulted in a shaggy black hog that looks like a traditional European wild boar. In the early 1900s, a local rancher brought about two dozen pure European wild boars to North Carolina to stock his hunting ranch. The boars were wily and about 60 to 100 escaped. Over time they interbred with feral hogs, domestic stock of local farmers that also roamed freely in the mountains. In the past century they have spread throughout the mountainous forests of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee.

NPS photo. Hogs that look very different from these black boars also appear. These hogs often have spots and sometimes even have curly tails. People presumably brought these hogs from other states and deliberately released them in the Park so they could hunt them. What do we do with non-native wildlife? In a typical year, wildlife managers actively trap and shoot wild hogs to stop habitat destruction and disease spread. Most of the work is done from December through June. In a typical winter, wild hogs move to the lower elevation areas where wildlife managers can more easily access them. In the spring and throughout the summer, hogs move to the higher elevation forest in the backcountry, making hog control much more difficult. In a typical year managers remove about 275 hogs from the Park—slightly more than half of those on the North Carolina side. Wildlife managers also work cooperatively with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, the USDA, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, and the Tennessee Department of Agriculture to monitor for wild hog disease and disease spread. These studies include taking blood samples from captured hogs and keeping track of capture locations. Other invasive animals are also problems for the Park, but many of these—the hemlock woolly adelgid and fire ant, to name a couple—are challenges that vegetation managers handle. Zoonic Diseases Diseases that wildlife can spread to people, either directly with an animal bite or indirectly through a vector such as a tick or flea, pose management challenges for wildlife staff. They always use personal protective equipment—gloves, goggles, and masks, if necessary—to prevent transmission of these diseases, which can include:

Keep in mind that most of these diseases are not common in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, but it is still wise to check yourself for ticks after visiting (or visiting any forested or grassy area). It is also unwise—and illegal—to willfully approach wildlife, because you put the animals and yourself at risk. |

Last updated: September 29, 2015