Free Africans on Virginia’s Eastern Shore

Most of the free Africans and their descendants in Virginia gained their freedom during the 17th and early 18th centuries before chattel slavery became the law of the land. While later free Africans and their descendants lived in almost all Virginia counties, in the early 17th century only Anthony and Mary Johnson and a few other free Africans migrated from the Jamestown area to Northampton County on Virginia’s eastern shore.

According to the Northampton County tax lists in 1664, there were 62 Africans living on the peninsula among the 450 others on the lists. From 1664 to 1677, there were 13 free African householders, including Anthony and Mary in Northampton.

The Place

The eastern shore of Virginia is a wide peninsula surrounded by the omnipresent Atlantic Ocean on the east and the Chesapeake tidewaters on the west. The land, swept by fierce northeasterner winter storms and from late July to October, is subject to the onslaught hurricanes blustering up the Atlantic coast. The colonists who raised crops and livestock. However, because of the lack of deep-water harbors they were unable to establish direct trade with sea-going vessels.

The same waters that brought storms also mitigated extremes in temperature found on the mainland. The average winter low of 40º F to a summer high of 75º F coupled with a substantial annual rainfall resulted in a growing season well over six months and bountiful crops of corn and tobacco.

Wild fowl and other animals were plentiful in the marshes and forests that offered livestock abundant feed. Oak, Hickory and Pine woodlands provided lumber for ship builders. The colonists dispersed themselves along the coves and inlets. The lack of good roads limited travel by land but the abundant inland waterways allowed Africans and English settlers to travel back and forth visiting family, kin, and friends.

Cultural Patterns: “Family First”

“Family First” might well have been the motto of Africans gaining their freedom after coming to Virginia. From their first years in Virginia colony until the mid-18th century, court records show that Africans married, struggled to gain their own freedom as well as the freedom of family members. They worked hard to keep their families together and raise their children under the extreme constraints imposed by servitude, tithable and other laws that increasingly circumscribed their freedom.

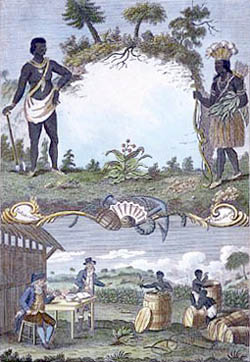

Tobacco Label depicts the labor expected of enslaved Africans in 17th and 18th century Virginia and Maryland.

Tithable laws required African men and women to pay the colony a share of tobacco and other crops they might raise. African men married to African women, had to pay the tithe for their wives and, if they had daughters for them as well. This made marriage a costly proposition, but marry they did. Read more about Tithable Laws.

In 17th century Virginia, marriage enhanced the standing of all men in the community, African or English. The significance of marriage for community standing was as a feature of African cultures just as it was in English culture. Marriage, family, and kin networks created and maintain the lineages that bound together West and West Central African societies.

African men sometimes married English or American Indian women and African women entered into unions with English men (Brown 1996:124–126). Interracial unions helped African men to decrease the tithes they paid to the Colony. Before 1662, children of interracial marriages were born free. After 1662, children of enslaved African mothers, were born into servitude no matter what their father status or his race.

The boundaries between free and enslaved status were permeable for Africans in early Colonial Virginia. Free people of color often held one or more family members in legal bondage to protect them from being sold and separated. Free African men often purchased their enslaved wives, and, fearful of legally imposed residence prohibitions upon freed “negroes,” held their wives and children as bond slaves. Free women sometimes purchased their enslaved husbands and daughters as property (Russell 1913 [1969]:91–92).

Reading between the lines in the court records of Francis Payne and Emanuel Driggus illustrate the value African men and women placed on family and kinship. While enslaved by Jane Eltonhead, Francis Payne entered an agreement with her to raise and share a tobacco crop. The first year he agreed to raise 500 pounds of tobacco and six bushels of corn. Then he agreed that in return for his freedom to provide Eltonhead with…

“‘Three Suffict men Servants betweene the age of fifteene and Twenty four [years] and they shall serve for sixe yearses or seaven att the Least, And that I Francis am to paye [for] those Servants [with] the next cropp…(Breen and Innes 1980:74–75).’”

After gaining his freedom, Payne worked thirteen years to pay “Three Thousand Eight hundred pounds of tobacco…for his…[continued]…freedom and the freedom of his wife and children (Breen and Innes 1980:74–75).” Emanuel Driggus entered a similar agreement to free two of his “daughters” who were in fact fictive kin. Although he worked diligently, he was not able to keep at least two of his children from being sold into permanent enslavement.

Marriage broadened kinship ties and created community networks. Driggus’ daughter Jane married a free African planter, John Goodsall. After his death, she protected what she, and by extension, her family had gained from marriage before entering into a second marriage. Jane required William Harman, her second husband to sign a marriage agreement stating her rights after marriage. The 1666 marriage connected Harman to the large Driggus clan. Seven years later, an aging Emanuel Driggus transferred property to his children and made a special provision for “my loving son in Law William Harman, Negro (Breen and Innes 1980:84).”

In addition to forming communities through marriage, free Africans of Northampton established community ties through commercial transactions. They sold each other cattle and horses for tobacco that they could in turn use as collateral for hiring indentured servants or purchasing freedom of family members. In their everyday affairs the Northampton, free Africans interacted and formed alliances with English men and women who were their neighbors. They used the tidal waterways to stay in contact with other African and English planters with whom they maintained commercial and social relations.

Material Cultural Patterns

Free or enslaved, 17th century Africans in Virginia did not greatly different from the English in their farming practices and technological skills The Dutch slave traders supplied mid-17th century Virginia with human cargo, Kongos” and “Angolas” seized from Portuguese ships or directly from Portuguese trading posts along the coast of West Central Africa (Sluiter 1997). Building on Sluiter’s note on the origins of Africans brought to Virginia in 1619; Thornton describes the likely material life of Angolans whom the Portuguese enslaved as a corollary to their West Central African military operations during that period. Most of those enslaved from this warfare were from urban settlements around the royal district of Ndongo. Central African cities were more rural than European ones, so that there was a great deal of farming going on nearby and many urban residents raised food crops and even domestic animals. They made clothing out of bark cloth as well as importing cotton cloth from as far away as the Kongo. They regularly attended regional and district markets where they obtained what they did not produce—iron and steel or salt (Thornton 1998: 431–32). Thornton’s descriptions correlate the records of Edmund Scarborough who imported “Angola” slaves to Northampton from New Amsterdam sometime during 1624–1664. Scarborough wrote the “Angolas” “‘practiced shifting cultivation and rotation of different crops. They knew how to work metals, including iron and copper, and they were skilled potters. They wove mats and articles of clothing from raffia tissues or palm cloth…They had domesticated animals—pigs sheep, chickens and in some districts cattle—though they did not use milk, butter, or cheese (Boxer 1969:96–103).’”

Men were more involved than women in raising livestock both in their homelands and in Virginia. The term “cow boys,” Ira Berlin tells us, entered American English as a reference to the colonial occupation of African men herding and tending cattle (Berlin 1974). Northampton free Africans had a thriving internal and external economy, selling cattle and tobacco for cash or exchanging them with one another for goods, food crops, and services. However, growing tobacco was the major agricultural labor carried out by almost all Africans and English indentured servants alike.

Mary and Anthony Johnson, other free Africans and their children in Northampton raised tobacco as well as livestock on their land. Read more about the lives of Mary and Anthony Johnson.

Systems of Meaning: Identity and Religion

The names of the earliest Africans to arrive in Virginia and Maryland, particularly those named in the court records of free Africans in Northampton County, lend credence to Thornton thesis that they were enslaved people from Angola or from neighboring Kongo. A large proportion of central Africans was Christian and received a Christian baptismal name, usually in a Portuguese form. Christianity and Christian names were deep-rooted in central Africa before the Atlantic slave trade. The BaKongo often used their baptismal name and saint’s name as an indication of their Christianity. If they were nobility they might also bear a series of Kikongo names that reflect their descent (Thornton 1993:729–730).

The form of Christianity in Angola, also predating the Atlantic slave trade resembled that in Kongo; when people were baptized as Christians, they took a baptismal name. Even non-Christians in Angola sometimes bore these names. Nobility usually had double names and while there is very little evidence about commoner naming patterns for the 17th century, what evidence there is suggests they followed the pattern of nobility. Thornton notes that slaves within Angolan societies might be Christian, known by a single name and that gaining their freedom was cause for an individual to take a double name (Thornton 1993:730, 732–735, 737). The naming patterns and practices of the few names of Africans in 17th century Chesapeake seem to conform with the central African naming patterns identified by Thornton (see table below), one indication that they retained their African identification.

Handler and Jacoby (1996) in an extensive study of African naming practices in Barbado (1650–1830), found enslaved people followed certain principles and practices of African naming procedures. They also contend “Creole” slaves i.e. those born in the Caribbean, generally named themselves although the majority of those names were never recorded (1996:689)

Kongo/Angola Naming Patterns and Practices of 17th Century Chesapeake Africans1

| Date | Name | Status | Naming Pattern | Naming Practice |

| 1619–1624 Jamestown2 3 4 |

Angelo | Enslaved | Christian (Saint?) | Single name |

| John Pedro | Enslaved | Christian Saint | Double name | |

| Antoney Negro | Enslaved | Christian Saint | Single name and descriptive English term? | |

| Isabell Negro | Enslaved | Christian Saint | Single name and descriptive English term? | |

| Antonio the Negro Changed to Anthony Johnson |

Enslaved Purchased freedom |

Christian Saint | Single name changed to double, anglicized on obtaining freedom | |

| Mary Changed to Mary Johnson |

Enslaved Husband purchased freedom |

Christian Saint | Single name changed to double, anglicized on obtaining freedom and/or marriage | |

| 1634 Maryland5 |

Mathias de Sousa | Apparently free “passenger” on the ship bringing first settlers to Maryland | Christian Saint | Double name |

| 1650–1665 Northhampton6 |

Manuel Rodriggus | Enslaved Purchased freedom |

Christian Saint | Double name, Anglicized both names to Emanuel Driggus |

| Mary Rodriggus | Enslaved Purchased freedom |

Christian Saint | Double? Or married name, Anglicized surname to Driggus | |

| Bashasar Farnado [sic] or Fernando |

unknown | Christian Saint? | Double name | |

| John Fransisco | unknown | Christian Saint First name Portuguese surname |

Double name | |

| Tony Longo | unknown | Christian Saint First name Angolan surname |

Double name | |

| Sebastian Cane | unknown | Christian Saint first name Anglican Surname |

Double name | |

| Francis Payne | Christian Saint first name Anglican Surname |

Double name Compadre to Driggus’ child |

Culture Change: Acculturated African Virginians?

There is little information to support or deny acculturation of 17th century Chesapeake Africans. The legal records through which we gain a glimpse of the early free Africans reveal little about their systems of beliefs, religion, or cultural ceremonies. The baptism of their children might imply some level of religious acculturation, but according to Thornton, people of West Central Africa had been Christians before the transatlantic slave trade began. On the other hand, from the first record naming of an African child, William in 1624, until almost the end of the century with the naming of Anthony Johnson’s grandson, John Johnson Jr. the African children named in the record consistently have English names (Breen and Innes 1980).

Among adults, by 1656, there were other free Africans with English names living in other Virginia Counties. Like the Johnson brothers, they may have been second or third generation native born Americans. Benjamin Doyle received a patent for 300 acres in Surry County that year. In 1668, two free Africans, John Harris bought 50 acres in New Kent County; and Phillip Morgan leased 200 acres in York County for 99 years.

The free Africans of the Chesapeake must have spoken sufficient English to communicate with white colonials and to be understood in the courts. Moreover, they seemed to understand the laws and processes of litigation more than sufficiently enough to their civil rights, make out and execute wills and conduct probate inventories. Interestingly, the women were as much at ease in these processes as the men were.

Counter Cultural Resistance: Litigation and Military Service

The families in Northampton routinely used the courts to settle property disputes, draw up contracts, file probate inventories, and wills. Men and women participated in these activities. Children of free African and English women petitioned the Virginia courts for their freedom (Brown 1996:212–213).

Generally, colonial legislatures excluded “Negroes” from armed service except during military conflict. During the earliest phases of settlement, all able-bodied men, English and “negro”, free men and slaves, were expected to defend against American Indian attacks. Once a colony was relatively secure, “negroes” then were excluded from serving in the peacetime militia (Fields 1998).

Under 17th century English law, African men owned property and paid taxes. Yet, in 1639, they were excluded by law from being armed.

“ALL persons except negroes to be provided with arms and ammunition or be fined at pleasure of the Governor and Council (Hening ed., 1823 The Statutes at Large, Vol. 1:226 [Emphasis added]).”

At one time or another, all colonies enacted legislation excluding “negroes” from serving in the militia. Virginia became the first to pass such a law in 1639 (Johnson 1969:10). However, when conflict with American Indians arose, the desperate need for additional manpower required the services of Africans. In those situations, government officials either ignored the statutes or simply changed them. Maryland’s 1715 law prohibiting any “Negro or other slave” from bearing arms off his master’s land would seem to preclude free Africans from militia duty. In Virginia, a 1723 law allowed free Africans who were householders or members of the militia to have one gun. A 1738 law required them to muster, but to appear unarmed (Fields 1998).

These colonies also excluded free Africans from the militia out of concern that they would lead slave rebellions (Bowman 1970:62). There were also economic considerations for excluding blacks. Since the enslaved men were private property, complications arose over how owners should be compensated, especially if their bondsmen were maimed or killed in combat. Historians have also suggested that because the peacetime militia also fulfilled an important social function, colonial African were excluded for the same reasons they were denied access to many other white-dominated social organizations (Donaldson 1991:2).

There is some evidence that suggests laws excluding “Negroes” from being armed were not always upheld by the English colonists. For example, even though arms and gunsmiths were generally scarce in colonial Virginia and Maryland, of the only 16 gunsmiths identified as present in Virginia between 1675 and 1726, David James, “a free Negro,” was bound to one of them. David was an apprentice to James Isdel in Princess Anne County to learn the “Trade of Gunsmith” (Gill 1974:91) Even an occasional reference to a “Negro” gunsmith is found in probate inventories by the mid-18th century. More telling is the archeological record from slave sites.

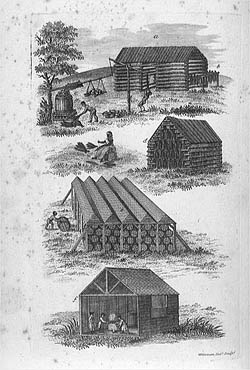

The Root Cellars Tell Another Story

English laws and fears not withstanding, the archeological record suggests they were hardly deterrents to colonial Africans maintaining a weapons cache. Archaeologist William Kelso uncovered a series of pit features (later interpreted as root cellars) where slave cabins associated with the Burwell plantation (later called “Carter’s Grove”) were located in the 18th century. The artifacts found in these pits included gun parts (Kelso 1984). Wheaton and Garrow made similar findings at three plantation sites in the Carolina Low Country. Slaves occupied the sites, Yaughan (1740–1790), Curriboo (1740–1800), Late Yaughan 1780 to 1820s), over a period of almost one hundred years. Balls, shot, gunflints, and parts were found in all sites, the greater number of artifacts were found on the sites occupied near the end of the 18th century. Faunal remains suggested the guns might have been used to hunt game (Wheaton and Garrow 1985). One might conjecture that if 18th century enslaved Africans and African Americans had guns and used them that the same may have been true for some free Africans during the 17th century.

As time passed and laws governing enslaved and free Africans became more and more onerous, free Africans and their Virginian-born descendants moved to southern counties of Virginia, north to Accomack County, the county of New Kent and into North Carolina. The first census of the United States in 1790 found, 12, 866 free “Negroes” in Virginia located in Accomack County, one county to the north of Northampton where the 17th century free Africans had lived. In the 1800 census, Accomack was the region in the South most heavily populated by free African-Americans numbers, throughout the Colonial Period, the majority of Africans and native-born African Americans in the Chesapeake were enslaved. The next section explores the life styles and cultural patterns of enslaved Chesapeake Africans in the colonial period.