USGS / Thomas Wayland Vaughan Plant science in the Dry Tortugas has a long history. The earliest plant inventories indicate that in the 1840s, Loggerhead Key was covered with "a large stand of old white buttonwood trees" that was cut or burned by island residents. Human development of the island began in 1856 with the construction of the U.S. Coast Guard lighthouse and associated lighthouse-keeper facilities. The Loggerhead Key lighthouse was first illuminated in 1858. Low-growing coastal vegetation dominated by bay cedar (Suriana maritima) is believed to represent the historic vegetation community on Loggerhead Key in the early 1900s.

USGS / Thomas Wayland Vaughan Loggerhead Key was chosen as the site for the new Carnegie Institution for Science of Washington DC, which established and supported the Tortugas Marine Biological Laboratory. The laboratory facilities were constructed on the northern end of the island. Two laboratory buildings, a dock with kitchen, an outhouse building, and a windmill for pumping salt water were built during the summer of 1904. The first scientists arrived shortly thereafter. Scientific activity was limited to the late spring and summer months to avoid working during the peak of hurricane season.

USGS / Thomas Wayland Vaughan Commissioned by the Carnegie Institution and prepared from information collected in 1904 by O.E. Lansing, the first known plant list contained 44 species. Over time, the plant life in the Dry Tortugas has been influenced by both human and natural forces. Human development on Loggerhead Key has had a profound effect on the vegetation of the island.

USGS / Thomas Wayland Vaughan Native vegetation was cleared away to make room for the construction of the lighthouse and its surrounding facilities, and later for the Carnegie Institution structures. Exotic ornamental landscaping plants, such as coconut trees (Cocos nucifera) and century plants, also known as sisal hemp (Agave sisalana), were imported to the island from elsewhere. Over the years, more introduced species such as fig (Ficus elastica), oleander (Nerium oleander), sea hibiscus (Hibiscus tiliaceus), and mahoe (Thespesia populnea) were planted to replace native vegetation as it was killed by hurricanes.

USGS / Thomas Wayland Vaughan Australian pine (Casuarina equisetifolia) was planted around the Carnegie Laboratory as a windbreak. By 1918, introduced plants were influencing the natural ecology of the island by producing shade and conserving water. By the 1940s, the once-dominant bay cedar was being replaced by prickly pear cactus (Opuntia stricta), coastal beach sandmat (Chamascyce mesembrianthemifolia), and century plant, among other species.

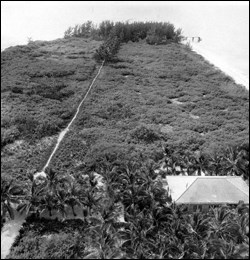

Florida Geological Survey / John Henry Davis By 1942, the most prolific exotic was Australian pine, which had been introduced by the director of the Carnegie Laboratory in about 1910 and had spread from its original planting locations with seedlings noted to be growing over many parts of the island. At that time, John Henry Davis had stated, "It is entirely possible that these trees will continue to grow and eventually replace the existing vegetation."

NPS photo By 1980, the words of John Henry Davis had come true, as nearly all of the native plant communities had been displaced and outcompeted by two species: Australian pine and century plant. With the establishment of Dry Tortugas National Park in 1992, resource managers began to assess the alterations to the communities of Loggerhead Key with the intent of restoring the island back to pre-settlement conditions. In 1995, an exotic plant management plan was developed and implemented for Dry Tortugas National Park. The plan called for eradicating Australian pine and century plant from Loggerhead Key. Both species had altered native plant communities and reduced the native habitats for island wildlife. The Problem

NPS photo Where Australian pine occurs on sandy beaches, the trees and their root systems hinder the movements and nesting activities of federally listed threatened and endangered sea turtles. Changes in beach morphology, from gentle slopes to steep embankments, often accompany the invasion, further exacerbating the problem of sea turtle habitat disruption. Ocean waves undercut the sand adjacent to the roots of trees, thereby steepening the embankments and making them difficult for sea turtles to surmount. The network of roots interferes with the excavation of nesting holes by adult females. Soft, debris-free sand is necessary for successful nest excavation, a condition that does not occur in or around the root systems of Australian pine. Fallen Australian pine trees physically hinder the movements of nesting turtles on the beaches and reduce the amount of available nesting beach. The consequences of these conditions include trapped turtles, hatchlings encountering roots, altered nesting routes, nesting in fallen branches, and turtles abandoning pits due to obstructions. In addition, the invasive plant species alter the composition and structure of terrestrial plant communities by outcompeting native plants, thus reducing species diversity in areas where the exotics are dominant. The natural habitats and food sources of native animals that use these communities similarly diminish. Management Activities

NPS photo The establishment and spread of exotic plants can have severe consequences for any environment but, due to the effects of geographic isolation, islands are especially vulnerable. Control of the ubiquitous Australian pine and century plant of Loggerhead Key was the focal point of the vegetation management action. The treatment and monitoring was carried out by the National Park Service. During 1994–2001 the U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service provided assistance with tree cutting and prescribed burning. An archeological survey was conducted to determine the effects that vegetation management actions may have on the island's cultural resources.

NPS photo Treated Australian pine trees were left standing except for trees adjacent to beaches, which were cut down and treated with herbicide to prevent them from falling and impacting sea turtle nesting habitat. In early 1998, the remaining acreage of Australian pine growing on the northern part of the island was cut down. The felled wood was burned, eliminating not only the Australian pine slash on the ground but also killing a large number of century plants. Century plants not killed by fire were treated with herbicide. Vegetative sprouts and seedlings of Australian pine and century plants continue to be controlled by hand-pulling and application of herbicides. Other invasive exotic species on Loggerhead Key occur only sporadically and are treated as they appear.

NPS photo Natural areas along the eastern beach strand were protected from management activities. These areas were monitored to determine if restoration objectives were being met. Monitoring was done by establishing a series of 10 permanent transects perpendicular to the axis of the island, along which vegetation was periodically measured. With the exception of the native community along the eastern beach strand, transects 1 through 5 are in an area that was heavily dominated by exotics. This area was used to monitor the response to the management activities. Transects 6 through 10 represent the native communities and were used as the target for defining restoration success. Vegetation Response

NPS photo During the pre-treatment sampling period of 1994–2001, a total of 48 species were identified on Loggerhead Key. Of those 48, 17 are considered exotic in origin, and 31 are native. Monitoring results within the treatment area have shown reductions in the numbers of exotics, with concomitant increases in the numbers of native species. Essentially all of the exotic species that were present in the managed areas in 1994 had been removed as of 2001. Visual observations of the beaches indicate that the removal of Australian pine has resulted in marked improvements in beach morphology. The beaches are returning to their gradually sloping nature without embankments and are largely free of surficial and buried roots and debris. Reducing the number of obstacles and restoring the natural condition of the beaches has improved the quality of habitat for nesting sea turtles and emerging hatchlings, and the vegetative restoration of Loggerhead Key has been deemed a success. The transformation of Loggerhead Key has been nothing short of remarkable. The vegetation structure of the island now visually approximates the pre-Australian pine condition. Future monitoring of the succession of native species will continue to shed light on the dynamics of the plant community's response to restoration.

NPS photo

Additional Resources

Dry Tortugas National Park: Loggerhead Key Exotic Plant Management and Island Restoration Project Download (PDF, 5.0 MB) |

Last updated: July 29, 2015