Project Gutenberg by Tom Walker

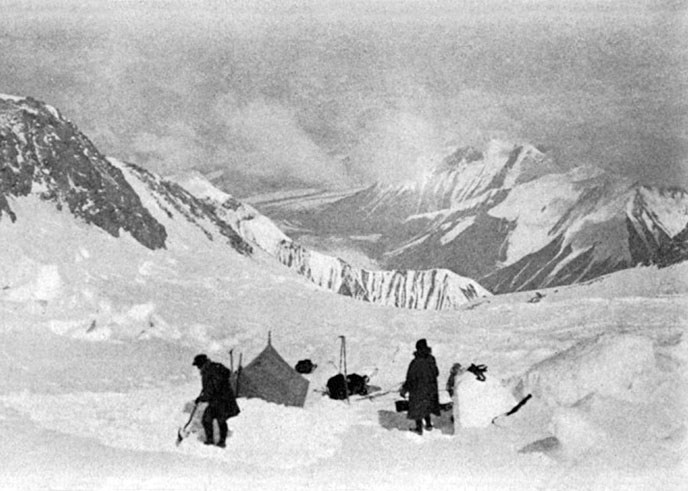

Harry Karstens, climb leader, Archdeacon Hudson Stuck, climb organizer, Robert Tatum, and Walter Harper, an Alaska Native, had travelled cross country by dog team in sub-zero cold to reach the mountain. Shortly after Easter they began relaying their ton and a half of supplies from the Kantishna mining district to the base of McKinley, fifty miles away. In mid-April, the expedition established camp in the last timber in Cache Creek, a few miles below McGonagall Pass an opening onto the Muldrow Glacier. Here they hunted for meat and gathered firewood and willow twigs for use during the ascent.The assault began with Karstens breaking trail up the Muldrow, a route Stuck called "the highway of desire." Using willows as markers Karstens laid out a route from McGonagall Pass to a cache at 8,000'. Once the trail hardened, team members followed with loaded dog sleds, the first of numerous relays. Day after day men and dogs toiled to move their supplies up the Muldrow to its head. The route rose gently in its first four miles, but where the glacier turned south, it inclined steeply between towering, slab-sided ridges. In a maze of lethal crevasses and huge blocks of ice, the team built numerous snow bridges in order to proceed. Avalanches were a constant threat. In early May, the expedition completed the first relay from their midway cache to 10,800', the site chosen for their last glacier camp. Several hours later as they again approached the site with another load, they saw smoke. "Had some mysterious climber come over from the other side of the mountain?" Hudson Stuck wondered. "Had he discovered our wood and our grub, and perhaps starving, kindled a fire?" The climbers pressed forward and found their cache in flames. They frantically doused the mystery blaze, but lost vital gear including three silk tents, clothing, and food stuffs. Sifting through the embers, Stuck determined that a careless match or spark dropped earlier had smoldered to life, igniting the fire. Six weeks into the expedition, the fire was the first setback in the press toward the ultimate prize. The work of the next few days would determine if they could continue on or be forced to retreat. Makeshift substitutions allowed the expedition to continue. Finally on May 30, the weather broke and after six exhausting relays, the climbers established a new camp at the top of the ridge beneath a rock outcrop, now known as Browne Tower. The laborious step cutting was behind them. Stuck later rejected any credit for conquering the ridge. "[I] would like to name that ridge Karstens Ridge," Stuck said, "in honor of the man who, with Walter's help, cut that staircase three miles long…" With two full weeks of food and fuel on hand, which could be stretched to three if necessary, the climbers were well-provisioned to wait out an extended storm, or even establish yet another, higher camp. Everything seemed primed for success but on Mount McKinley, there is no sure thing. Archdeacon Stuck, so near his long-cherished goal, was failing. For days, he had been convulsed by choking and shortness of breath, even blackouts. Only his extraordinary will and the excellence of his companions had gotten him this high. "Deacon having hard time breathing but we will get him there somehow," Karstens declared. On the evening of June 6, the eve of the summit attempt, Harper cooked a meal that quickly wrought internal havoc on his companions. After a few hours of fitful rest, the men left camp for the summit at three a.m. The temperature was -21°F.

Just past mid-day, Walter Harper stopped. He could go no higher. After weeks of toil, he had reached the top of North America's tallest mountain. Karstens and Tatum came seconds behind. Stuck, the last man on the rope, collapsed unconscious on the summit. Despite the stabbing cold and draining fatigue, the climbers exulted in the stunning vistas. Even in full sunlight, the temperature was just 7°F. The team spent an hour-and-a-half on the summit reading instruments and holding a brief prayer service before the cruel wind drove them down. Before leaving, they planted a small cross and unfurled a handmade American flag. Only during the weary descent to high camp, did the full enormity of their triumph sink in. "I remember no day in my life so full of toil, distress, and exhaustion, and yet so full of happiness and keen gratification," Stuck explained. Karstens put it more simply: "Hurrah. The south summit of Mount McKinley has been conquered." |

Last updated: March 29, 2017