WHAT ARE ZEBRA & QUAGGA MUSSELS? Both zebra and quagga mussels can survive cold waters, but need waters above 48 degrees F to reproduce. Zebra mussels are native to the Black and Caspian Seas, while quaggas are native to the Dnieper River drainage in the Ukraine. Both species were discovered in the Great Lakes in the late 1980’s, when they were discharged in ballast water of ocean-going ships. They “hitched rides” to other waters in the United States on boats, trailers and equipment people transport from place to place. Until two years ago, these mussels had not spread west of the 100th Meridian. The first confirmed sample in Colorado was found in Lake Pueblo in January of 2008. Mussel larvae were positively identified in several lakes in July of 2008 in Grand County, including Grand Lake, Grandby, Shadow Mountain and Willow Creek. In October of 2009, mussel larvae were also confirmed in Jumbo reservoir in Logan County and Tarryall Reservoir in Park County. There is no way to determine when and where mussels first entered the state of Colorado.

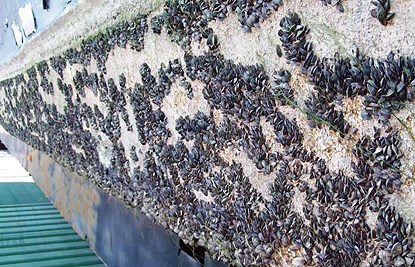

WHY SHOULD WE BE CONCERNED ABOUT MUSSELS? They grow and reproduce exponentially. A single female can produce up to one million eggs a year. Even if only ten percent of the offspring survive, there would be 10 septillion mussels in the waterway at the end of five years. They clog water infrastructure, impacting water supply and quality. They attach to most underwater structures and can form dense clusters that impair facilities and impede the flow of water. They clog intake pipes and trash screen, canals, aqueducts and dams. The mussels also degrade water quality and can alter the taste and smell of drinking water. They have significant ecological impact. They have the ability to change aquatic ecosystems and native plant and animal communities. The amount of food they eat and the waste they produce had life-altering effects on the ecosystem and can harm fisheries. As filter feeders, these species remove large amounts of microscopic plants and animals that form the base of the food chain, leaving little or nothing for native aquatic species. They have recreational impact. These mussels encrust docks and boats, and can get into engine cooling systems causing overheating and damage. The weight of attached mussels can sink navigational buoys, breakwaters, docks and small vessels. They have significant economic impact. The maintenance costs for power plants, water treatment facilities and water delivery infrastructures increase, so does the cost of food and utilities. In the Great Lakes area, maintenance costs in water treatment plants, power plant intakes and dams have been in the billions of dollars. The destruction of native fisheries also has a wider economic impact in terms of tourism and recreation dollars not spent. They are very difficult to kill. In only one instance have managers been successful in eradicating zebra mussels, and that was an isolated 12-acre quarry in Virginia. A large volume of chemical was used to treat the water and kill adults and larvae. Eradicating or treating zebra or quagga mussels in large water bodies and/or connected waterways may not be possible, so prevention is very important. They spread very quickly to other water bodies. Mussels can spread to other bodies of water by attaching to boat hulls and anchors, trailers, and fishing equipment. Larvae can be transported in bilge water, ballast water or live bait wells. Mussel larvae also disperse naturally and can be carried by water currents to other lakes or reservoirs downstream or through water diversion. WHAT CAN WE DO? |

Last updated: February 24, 2015