Last updated: January 5, 2026

Article

Black Churches of Beacon Hill

Massachusetts Historical Society

Between 1805 and 1840, the Black community of Boston organized five churches on the north slope of Beacon Hill. These churches served as spiritual centers and played a central role in the political and cultural lives of Black Bostonians. As historians James Horton and Lois Horton wrote in their groundbreaking work, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North, the Black church provided:

a training ground for leaders, a place where common laborers could gain positions of status as deacons and officers of church groups, a place for the education and training of the young, a place for entertainment and social life, and a meetinghouse for the exchange of thought, both political and social, free from the pressures of white society.[1]

Though Black Bostonians, both free and enslaved, attended White churches prior to the 1800s, they often faced discrimination there. Some churches required Black worshippers to sit in the “Negro Pew,” or in the least desirable galleries.[2] They also could not hold leadership positions and had to worship in the style and manner dictated by the White church leadership. The desire to be rid of these discriminatory practices, in part, influenced the establishment of the first independent Black churches in Boston.

More importantly, however, members of Boston’s Black community established their own churches to create their own welcoming religious environment as well as meet the needs of their community. Free from the control of White leadership, Black congregations could choose their own ministers, worship in the style they wanted, and use their buildings as gathering spaces for the community. As historian Roy Finkenbine wrote, the Black churches:

became much more than just religious institutions, housing schools and hosting political meetings, concerts, debates, benevolent and moral improvement societies, and other gatherings. Outside the family, they were the central institutions in black life.[3]

The first Black church in Boston formed in 1805. Founded under the leadership of Reverend Thomas Paul, the First African Baptist Church built its meeting house on Smith Court and met there from 1806 to 1898. This church became a major center of Black life and culture in 1800s Boston, housing a school room and serving as a gathering space for numerous community and abolitionist meetings. Read more about this church, and the important political and social events that occurred there, in the African Meeting House webpage.

Boston Public Library

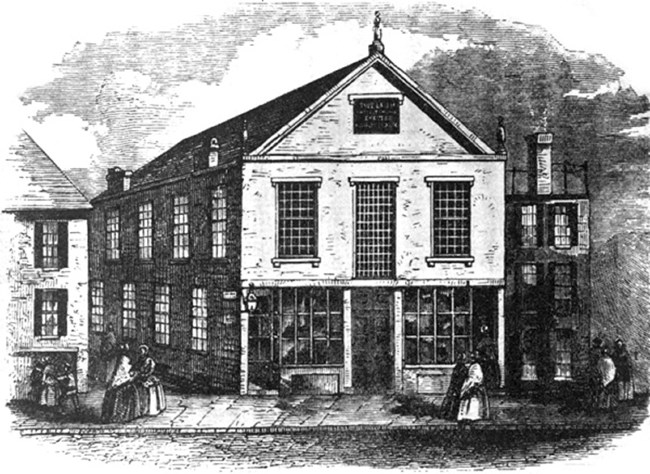

The Methodist Episcopal Church became the second Black church founded in Boston. In the early 1800s, many African Americans attended the Bromfield Street Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1818, this church helped to establish a separate Black Methodist church by hiring the Rev. Samuel Snowden. This church became known as the Revere Street Methodist Episcopal Church.[4] They met at various locations until the New England Methodist Conference purchased a building on Revere (originally May) Street in 1823. This church moved in 1835 to a larger building on Revere Street. The Rev. Snowden, like the ministers who followed him, actively participated in antislavery activities, such as the Underground Railroad. Influential members of the church included David Walker, an antislavery advocate and author of the Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World and Expressly to the Coloured Citizens of the United States.[5] After the Bromfield Street Church, which owned the Revere Street Church building, sold the building in 1903, the Revere Street Church no longer had a place to meet in Beacon Hill. They moved into a church in the South End in 1911 and again into another building in 1949. This church remains today on Columbus Avenue and is known as the Union United Methodist Church.

The First African Methodist Episcopal Bethel Society of Boston, later known as the Charles Street AME Church, organized in November 1833. Itinerant minister Noah Caldwell Cannon organized this church and served as its first minister. The church grew slowly in its early years. By 1844, they purchased a building on Anderson Street. The church remained there until 1876 when they purchased Charles Street Meeting House. In the later 1800s and early 1900s, the church hosted numerous community meetings as well as the First National Conference of Colored Women in America in 1895. In 1939, it became the last Black institution to leave Beacon Hill. The congregation is now located on Warren Street in Roxbury.

The Columbus Avenue AME Zion Church, as it is known today, began in 1838 when seventeen people withdrew from the Revere Street Methodist Church. They left to associate themselves with the African Methodist Episcopal Zion denomination, an organization led by African Americans. Appointed at the Annual Conference in 1838, the Rev. Jehiel C. Beman served as the church’s first minister. Like other Black religious leaders, Beman also played a major role in the antislavery movement. By October 1840, the church had over 140 members and in 1841 they moved into a small chapel, sometimes known as Rush Chapel, on West Center (now Anderson) Street.[6] Eliza A. Gardner, a prominent abolitionist and women’s rights leader, went to this church for over 75 years and held leadership positions there. The church moved to North Russell Street in 1866 and to Columbus Avenue in the South End in 1902.

Anthony Burns: A History by Charles E. Stevens, 1856.

Formed in 1840, Twelfth Baptist Church began when forty-six people left the First African Baptist Church (African Meeting House) along with the Rev. George H. Black. The reasons for this church schism are not clear.[7] Twelfth Baptist struggled for many years until the Rev. Leonard A. Grimes became minister in 1848. Born free in Virginia, Grimes had worked in Washington D.C. and became involved in the Underground Railroad. Grimes continued his Underground Railroad activity while serving as minister of Twelfth Baptist, also known as "The Fugitive Slave Church." Scores of self-emancipated freedom seekers received aid from Twelfth Baptist Church, and many chose to remain with this congregation. Lewis and Harriet Hayden, Shadrach Minkins, Anthony Burns, and Thomas Sims all worshipped at Twelfth Baptist. Twelfth Baptist Church constructed a building at 43-47 Phillips Street between 1850 and 1855, remaining there until 1906. Grimes continued as pastor until his death in 1874. Twelfth Baptist Church relocated to Warren Street in Roxbury in 1906 where it remains to this day.

The five Black churches of Beacon Hill played crucial roles in the lives of Black Bostonians and those who came to the city, including freedom seekers. They served as powerful agencies of community organization, education, and resistance. In addition to meeting the day to day spiritual and physical needs of their members, the Black churches of Beacon Hill helped lead the charge against slavery and discrimination in the city. As historian Roy Finkenbine wrote, these churches:

instructed members that slavery was a sin and that resisting the institution was a virtuous act. Black clergy and lay activists alike held that God sanctioned acts of protest and defiance aimed at eradicating social evils...religious motivation lay behind most black antislavery efforts in the city...Focusing on this world as well as the next, they provided meeting places, manpower, money, and motivation for the fight against slavery.[8]

Footnotes:

[1] James O. Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1999, originally 1979), 41.

[2] Roy E. Finkenbine, "Boston’s Black Churches: Institutional Centers of the Antislavery Movement," Courage and Conscience: Black and White Abolitionists in Boston, Edited by Donald M. Jacobs, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993), 170.

[3] Finkenbine, 171.

[4] Finkenbine, 172.

[5] Finkenbine, 181.

[6] Finkenbine, 173.

[7] Horton and Horton, 43.

[8] Finkenbine, 184-186.