Last updated: October 15, 2018

Article

Women's Suffrage and WWI

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Ann Lewis Women's Suffrage Collection

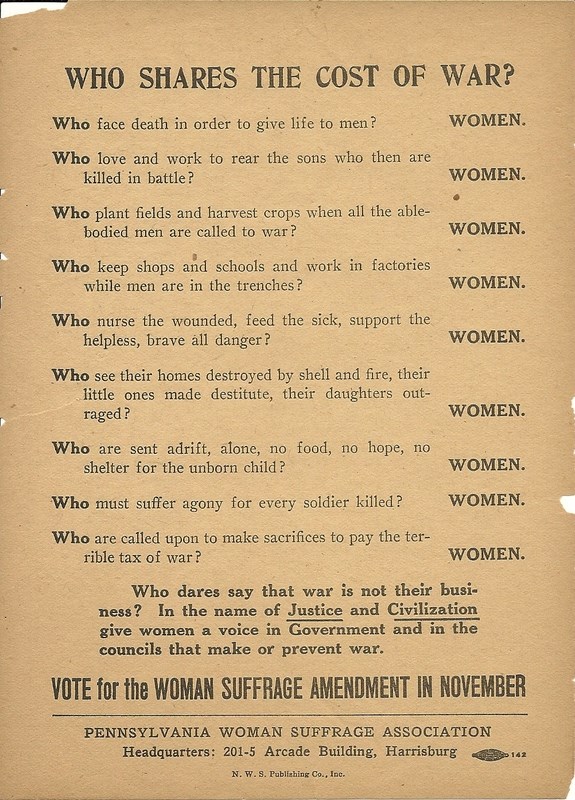

Despite the state victories, general support for a federal amendment was not gaining enough traction. But in the trying circumstances of World War I, proponents found a new rallying cry. American women served as a bulwark for American society during the War, making sacrifices in their personal lives and buttressing the country’s economy suddenly without its male workforce. Their contributions, which enabled the country to pursue the war effort, seemed unfair to many, given their inability to contribute to society as full citizens. To further their cause, American women took lessons from women elsewhere, who argued for universal suffrage as a war measure. American suffragists promoted universal suffrage as the only right path for a civilized nation to take, using as examples other countries involved in the war that had already adopted or were about to adopt universal suffrage, such as Canada, England, Russia, France, Denmark, and Italy. Even before the US entered the war in 1917, American women participated in war-related events such as the International Congress of Women in the Netherlands, in 1915, which argued for an end to the war and peace in Europe. One of the Congress’s “Principles of a Permanent Peace” was the Enfranchisement of Women: “Since the combined influence of the women of all countries is one of the strongest forces for the prevention of war…this International Congress of Women demands their political enfranchisement.”

President Woodrow Wilson, despite his previous position that suffrage should be left to the states, eventually used this very argument to encourage adoption of the federal amendment in his address to the United States Senate on Sept. 30 1918: “I regard the concurrence of the Senate in the constitutional amendment proposing the extension of the suffrage to women as vitally essential to the successful prosecution of the great war of humanity in which we are engaged.” World War I laid bare the unequal nature of American society. In the minds of many, men and women alike, how did it look for the United States to fight for liberty around the world while half its citizenry was denied the right to participate as equals?

Ann Lewis Women's Suffrage Collection