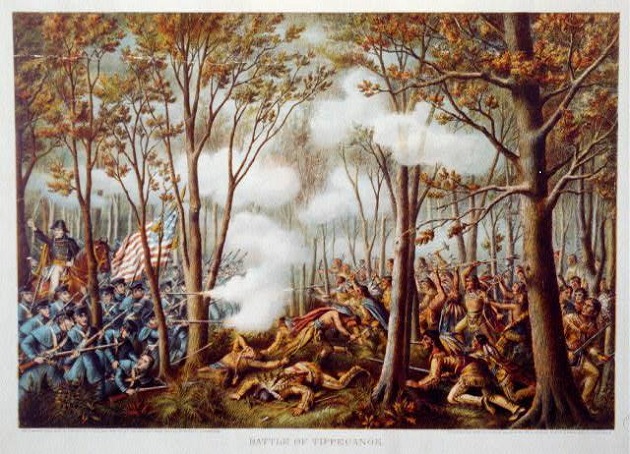

Fought almost a year before the formal declaration of the War of 1812, “Tippecanoe” became a rallying cry for many Americans as they denounced British support for the western Indian tribes.

"The depredations of the Indians…are instigated and supported by the British in Canada.” —the Niles Weekly Register

Library of Congress

“Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” became a popular campaign slogan in the mid-nineteenth century, promoting the Whig presidential candidate and war hero William Henry Harrison and his running mate, John Tyler. But decades before it became a political refrain in the 1840 presidential election, the battle it referenced helped drive Americans to war in 1812.

William Henry Harrison joined the army at eighteen in the early 1790s. He later became aide to Major General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, and participated in the decisive victory over the Western Indian Confederacy at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers. After resigning from the army, Harrison became a territorial governor. A ruthless negotiator for Indian lands, Harrison procured some 3,000,000 acres for white settlement by negotiating with carefully-selected tribes.

Harrison’s methods made him enormously popular with white settlers. The same methods outraged native Americans, inclusidng Shawnee brothers Tecumseh and Tenskwatawa, “the Prophet.” The brothers hoped to establish a confederacy of tribes that could turn back the waves of white settlers in the present day Midwest.

Harrison recognized the threat Tecumseh’s movement posed for American settlement. Hoping to gain an advantage, Harrison launched a preemptive strike at the native headquarters at “Prophet’s Town,” located on Tippecanoe Creek in present-day Indiana. But his targets sprang their own surprise: on November 6, 1811, they launched a predawn attack. Harrison’s men eventually repulsed the attackers, but suffered significant casualties in the fighting.

Harrison endured criticism on a number of fronts in the aftermath of the battle. Opponents charged him with neglecting to adequately secure and fortify his camp, and with fueling rather than defusing native resistance. Critics also held that Harrison’s actions had driven Tecumseh and his movement more firmly into the British camp.

But President Madison was hoping to unite both the country and his divided party for war, and was eager for a symbolic military success. And so the Republican press touted Tippecanoe as a resounding triumph.

The name “Tippecanoe” went on to became part of the American lexicon, as shorthand for the American accusation that the British were inciting an “Anglo-Savage War.” Ultimately, that charge that pushed the two sides closer to confrontation over Canada.

Last updated: May 24, 2016