Last updated: July 28, 2023

Article

The North Carolina State Capitol: Pride of the State (Teaching with Historic Places)

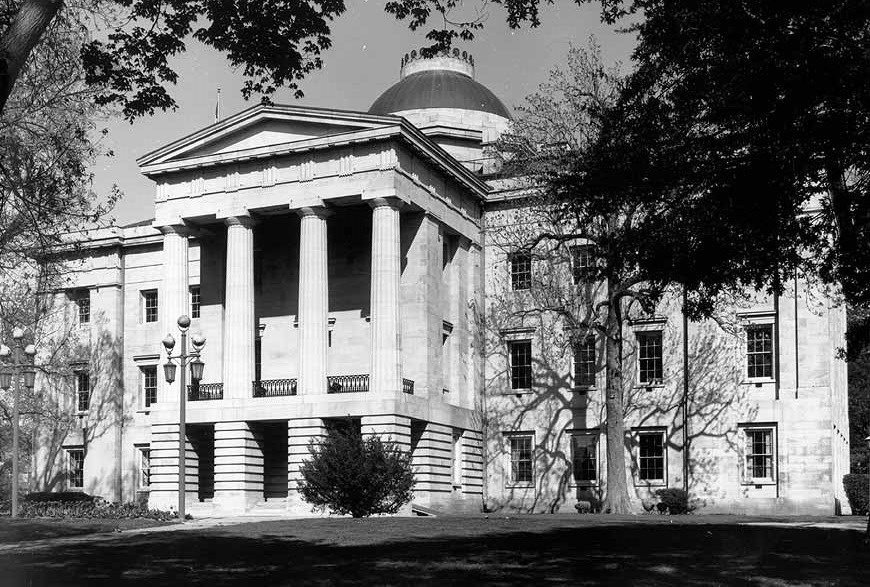

North Carolina's state capitol rises majestically on Union Square in downtown Raleigh, a city specifically created in 1792 to serve as North Carolina's permanent capital. Built between 1833-40, the granite building is one of the finest and best preserved examples of civic Greek Revival architecture in the United States. Relatively small in comparison to many other state capitols, this impressive structure has stood as a symbol of pride to North Carolinians for more than 150 years.

About This Lesson

This lesson is based on the National Register of Historic Places registration file, "Capitol" (with photographs), and other sources on the State House and Raleigh. North Carolina State Capitol was written by Howard Draper, Tour Coordinator and Historic Interpreter at the North Carolina State Capitol. The lesson was edited by the Teaching with Historic Places staff. TwHP is sponsored, in part, by the Cultural Resources Training Initiative and Parks as Classrooms programs of the National Park Service. This lesson is one in a series that brings the important stories of historic places into the classrooms across the country.

Where it fits into the curriculum

Topics: This lesson could be used in American history courses in units on the early National period, North Carolina state history, or early 19th-century politics and government.

Time period: Early 19th century

United States History Standards for Grades 5-12

North Carolina State Capitol:Pride of the State relates to the following National Standards for History:

Era 3: Revolution and the New Nation (1754-1820s)

-

Standard 2A- The student understands revolutionary government-making at national and state levels.Era 4: Expansion and Reform (1801-1861)

-

Standard 4B- The student understands how Americans strived to reform society and create a distinct culture.

Curriculum Standards for Social Studies

National Council for the Social Studies

North Carolina State Capitol: Pride of the State relates to the following Social Studies Standards:

Theme I: Culture

-

Standard C - The student explains and give examples of how language, literature, the arts, architecture, other artifacts, traditions, beliefs, values, and behaviors contribute to the development and transmission of culture.

Theme II: Time, Continuity and Change

-

Standard D - The student identifies and uses processes important to reconstructing and reinterpreting the past, such as using a variety of sources, providing, validating, and weighing evidence for claims, checking credibility of sources, and searching for causality.

-

Standard F - The student uses knowledge of facts and concepts drawn from history, along with methods of historical inquiry, to inform decision-making about and action-taking on public issues.

Theme III: People, Places and Environments

-

Standard A - The student elaborates mental maps of locales, regions, and the world that demonstrate understanding of relative location, direction, size, and shape.

-

Standard D - The student estimates distance, calculate scale, and distinguish's other geographic relationships such as population density and spatial distribution patterns.

-

Standard G - The student describes how people creates places that reflect cultural values and ideals as they build neighborhoods, parks, shopping centers, and the like.

Theme VI: Power, Authority and Governance

-

Standard C - The student analyzes and explains ideas and governmental mechanisms to meet wants and needs of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, and establish order and security.

-

Standard E - The student identifies and describes the basic features of the political system of the United States, and identify representative leaders.

-

Standard I - The student gives examples and how governemnts attempt to acheive their stated ideals at home and abroad.

Theme IX: Global Connections

-

Standard F -The student demonstrate understanding of concerns, standards, issues, and conflicts related to universal human rights.

Theme X: Civic Ideals and Practices

-

Standard A - The student examine the origins and continuing influence of key ideals of the democratic republican form of government, such as individual human dignity, liberty, justice, equality, and the rule of law.

-

Standard C - The student locate, access, analyze, organize, and apply information about selected public issues recognizing and explaining multiple points of view.

-

Standard D - The student practice forms of civic discussion and participation consistent with the ideals of citizens in a democratic republic.

Objectives for students

1) To examine North Carolina's early history and discover factors that influenced the establishment of the state's permanent capital.

2) To investigate the building history of North Carolina's State House.

3) To explain why many early 19th-century public buildings in the United States were designed in the Greek Revival architectural style.

4) To locate examples of Greek Revival architecture in their own community.

5) To discover the history of their own state capitol building.

Materials for students

The materials listed below either can be used directly on the computer or can be printed out, photocopied, and distributed to students. The map and images appear twice: in a low-resolution version with associated questions and alone in a larger, high-quality version.

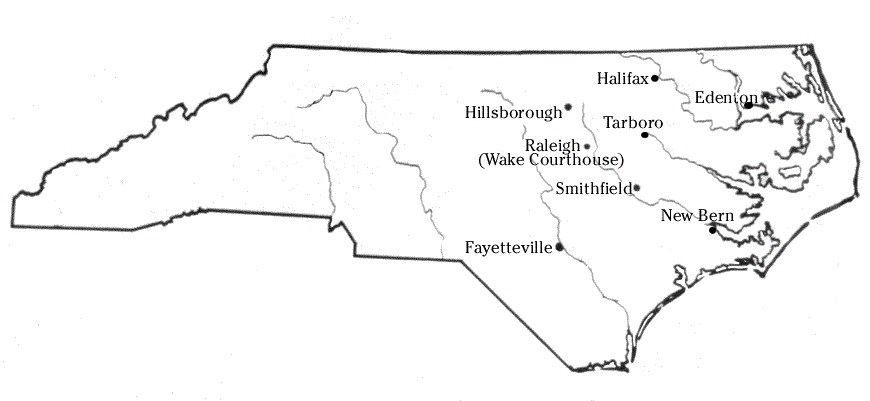

1) a map of North Carolina showing early meeting sites for the state legislature;

2) three readings that describe how Raleigh became the capital and how the capitol building evolved;

3) a painting and a drawing of the early capitols;

4) three photos of the capitol building today;

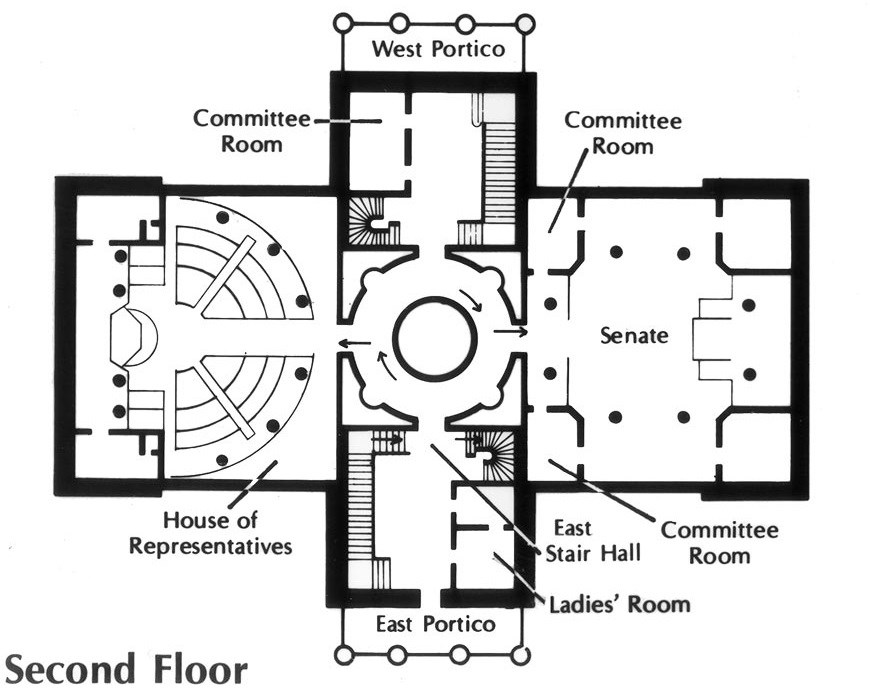

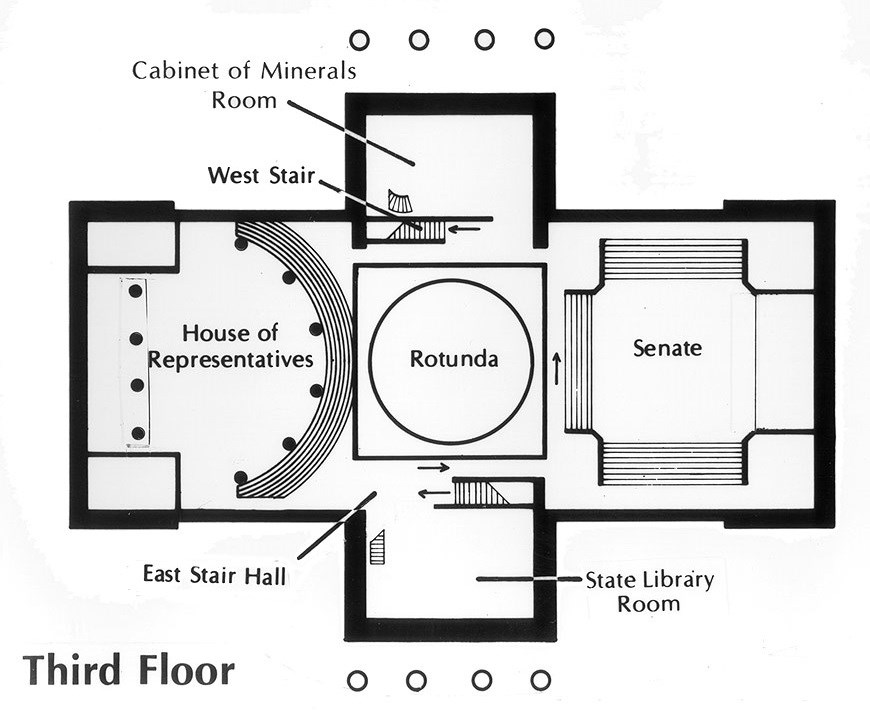

5) floor plans of the second and third floors of the capitol building;

6) a photo of a statue of George Washington located in the capitol building.

Visiting the site

The North Carolina State Capitol is located in downtown Raleigh, North Carolina, on Union (Capitol) Square. The Capitol is open to the public 8 a.m.-5 p.m. Monday-Friday, 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Saturday, and 1 p.m.-5 p.m. Sunday, except for New Year's Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. For additional information, contact the North Carolina State Capitol, 109 E. Jones Street, Raleigh, North Carolina 27601-2807.

Getting Started

Inquiry Question

Setting the Stage

In 1663, England's King Charles II granted the territory of Carolina, which included land stretching from Virginia to Florida, to a group of eight men. Known as proprietors, they were given the authority to control the land and establish a government. From 1691 to 1712, North Carolina's government was administered by a deputy who served under the governor of the province of Carolina. After 1712, North Carolina became a separate province with its own governor. The province grew slowly, however, and proved unprofitable for the proprietors.

North Carolina became a royal colony in 1729 when King George II purchased the land from the proprietors. The next 40 years brought the first period of marked progress evidenced by a stable government, steady population growth, and improvements in transportation and agriculture. Settlements expanded, and many new counties and towns were established. In 1774, North Carolina residents met in the town of New Bern, which was serving as the capital, to elect delegates to the first Continental Congress. This act defied the wishes of the Royal Governor, who was appointed by the King of England. Royal rule ended the following year when the Governor fled New Bern. On November 12, 1776, the first state constitution was drafted at Halifax by the Fifth Provincial Congress.

During and after the American Revolution, the legislature (the official body of lawmakers) met at several different locations in North Carolina. As was true in other states, the question of where to locate a permanent capital, the place where a government meets to enact laws, sparked heated debate. Finally, the town of Raleigh was mapped and laid out specifically to serve as the capital in 1792.

Locating the Site

Map 1: North Carolina.

Each of the towns indicated on the map served as a meeting site for North Carolina's legislature at one time. New Bern and Raleigh, however, are the only two towns to serve as the official capital.

Questions for Map 1

1. Locate Edenton, where the legislature met from 1722-37, 1740-41, and 1743. Next, locate New Bern, which served as the capital from 1766 until 1792. What do their locations have in common? Why might they have been logical locations for the legislature to meet at the time? What might have been problems with their locations?

2. Note the locations of the various towns where the legislature met during the American Revolution: Hillsborough, Halifax, Smithfield, Wake Courthouse, Fayetteville, and Tarboro. What do their locations have in common?

3. Locate Raleigh, which became North Carolina's permanent capital in 1792. How would you describe its location? What might have been some advantages of locating the capital here?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Establishing a Permanent Capital in North Carolina

New Bern was serving as the capital of North Carolina when the Revolutionary War began in 1775, but during the course of the war, the legislature (the official body of lawmakers) also met at Hillsboro, Halifax, Smithfield, Wake Courthouse, Fayetteville, and Tarboro. While the capital officially remained in New Bern, the legislature moved often in an attempt to prevent British troops and their powerful navy from gaining control of the government. The first meeting sites of the legislature lay along the coastal plain, but continued fighting convinced the legislators (members of the legislature) that a permanent capital needed to be located inland where it was safer. The combination of war and the moves resulted in chaotic conditions: official papers were misplaced or lost, and legislators and other citizens often did not know to where the legislature had been moved. Many legislators elected from distant counties failed to attend meetings because travel was difficult.

After the war, lively disputes ensued over where to locate the permanent capital of North Carolina. The residents of Fayetteville argued most vehemently for their town to become the capital. Although not the most populous town in North Carolina, Fayetteville had become the commercial center of the state. The town possessed new roads and bridges, and it was situated at the head of the navigable Cape Fear River. In 1788, the State Assembly instructed its delegates to "fix on the place for the unalterable seat of government." Another three years passed before a committee was appointed to select the precise site of the new capital. Nine members from each of the judicial districts in the state and one from the state-at-large formed the committee.

Committee members agreed that the early meeting sites of New Bern and Tarboro were too far east to be convenient for most of the state’s population. They believed the western part of the state would soon hold the balance of population and, therefore, the power in the state because so many people had moved inland by this time. As early as 1790, six of the 10 counties with a population greater than 10,000 were located in the western part of the state. This shift in population created a new sense of urgency to give western counties greater representation. Rather than designate an existing town as the permanent home for North Carolina's government, the committee ultimately decided to establish the capital in Wake County, home of a popular tavern where the committee met. The tavern was a favorite stopping place for lawyers, judges, and legislators who traveled around the state.

After the committee selected Wake County as the proper area for the capital, a precise site had to be chosen. Unfortunately, the commissioners left no record explaining why they decided to buy 1,000 acres of fellow commissioner Joel Lane's land, which was located 10 miles from the tavern where the meeting took place. The traditional story, which may be more legend than truth, was that the tavern's owner sold generous helpings of a popular alcoholic concoction known as cherry bounce. Commissioners may have sampled too much of this drink during the course of the evening. The next morning they discovered they had agreed to Lane's proposal to build the town on his land.

The citizens of Fayetteville naturally protested the committee's choice. They circulated a petition in Cumberland County which stated that "the establishment of a seat of government in a place unconnected with commerce and where there is at present no town would be a heavy expense to the people..." and that "the town when established never can rise above the degree of a village."1 The protest proved fruitless, however, and in 1792, the town of Raleigh in Wake County was mapped and laid out.

Questions for Reading 1

1. Why did the legislature's meeting site change frequently during the American Revolution?

2. Why do you think the citizens of Fayetteville "argued vehemently" for the capital?

3. Why was Raleigh selected over Fayetteville? What would be some advantages and disadvantages of creating a new capital as opposed to designating an established city as a capital?

Reading 1 was compiled from North Carolina State Capitol Education Staff, "A Tour of the Capitol," 1994; John A. Oates, The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear (Fayetteville: John A. Oates, 2nd edition, 1972); Kemp P. Battle, The Early History of Raleigh: The Capital City of North Carolina (Raleigh: Edwards and Broughton, 1893); William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989); and several untitled articles in the State Capitol files.

1John A. Oates, The Story of Fayetteville and the Upper Cape Fear (Fayetteville: John A. Oates, 2nd edition, 1972), 260.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: A Source of Pride for a Sleeping State

When Raleigh was established in 1792, the town consisted of four 99-foot-wide streets, a few 66-foot-wide streets, and five public squares. One of the squares occupied the center of the new town and was reserved for a capitol building, or State House, to house the state government. The North Carolina legislature set aside $10,000 to build the State House, which was completed in 1796. In 1822, William Nichols, the state architect, was hired to make the plain, small building more elegant. Between 1822-26 he stuccoed the exterior and added classical details which made the State House more fashionable; in addition, he added a third floor, rotunda, and dome.

On June 21, 1831, the remodeled capitol building was destroyed by fire. Ironically, a smelting pot of zinc being used to fireproof the building tipped over onto the roof and started the blaze. For the next 18 months, Raleigh's status was uncertain as the debate over moving the capital to Fayetteville reopened. The original protest that Raleigh would "never rise above the degree of a village" had proven true. Fayetteville, on the other hand, maintained its commercial advantages. If designated the capital, the town expected to become a metropolis, something North Carolina still lacked. Fayetteville failed to gain enough support, however, and Raleigh remained North Carolina's capital.

In December 1832, the legislature agreed to build a new capitol on the original site. They appropriated $50,000 and established a board of commissioners to plan a building similar to the old State House, but larger as well as fireproof. The commissioners selected the New York architectural firm of Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis to design the structure. The Town-Davis firm was famous for designing buildings in the Greek Revival Style, which was closely identified with the monumental public buildings of the nation's capital city, Washington, D.C., and the government buildings of several states. The firm already had completed the Connecticut State Capitol in New Haven and was at work on Indiana's capitol building. Town presented a plan for North Carolina's capitol, but the legislators felt the design looked too much like a Greek temple. William Nichols, Jr. was then asked to submit a plan for a capitol that would more closely resemble the remodeled building his father had executed.

Construction began on July 4, 1833, but Nichols's involvement in the project soon ended. The legislature then reappointed Town and Davis to continue construction. Although the walls already had been begun, Town modified the design to reflect the Greek Revival Style. This time, the legislature approved the design. In the fall of 1834, David Paton, a young architect from Scotland, took charge of construction. He brought in several skilled stonemasons, and with some of his own changes, completed the North Carolina Capitol in 1840. A festive celebration lasting from June 10-12, marked its completion.

The commissioners had asked for a "structure that would be an object of pride and admiration for the people of a State that had little in the way of man-made splendor."1 In fact, it was reported early in the project by a legislative committee that the commissioners had sacrificed "much of convenience and comfort" to the desire to build "a noble monument to...the people of North Carolina."2 The committee's desire for such a noble monument had cost almost $533,000—more than three and one-half times the state's total revenue in 1840. The results seemed to justify the expense. When the building was completed, the commissioners reported proudly that "the State possesses a building which for solidity & beauty of material, uniform faithfulness of execution, and for Architectural design, is not surpassed, if indeed equaled, by any building in the Union....And to North Carolinians it will remain for Centuries, an object of just & becoming pride, as a noble monument of the taste & liberality of the present generation."3 A contemporary report stated: "this political Temple, the Capitol of North Carolina, will vie with any legislative building in the Union, if not the world, and presents one of the finest specimens extant of classic taste in Architecture."4

Questions for Reading 2

1. Why was the first State House of North Carolina remodeled? What happened to the building in 1831?

2. Why do you think the building commissioners wanted a grand and elegant capitol?

3. Do you think a building can boost citizens' pride in their state? Why or why not?

Reading 2 compiled from Catherine Bishir, North Carolina Architecture (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1990); Henry Russell Hitchcock and William Seale, Temples of Democracy: The State Capitols of the U.S.A. (New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1976); North Carolina State Capitol Education Staff, "A Tour of the Capitol," 1994; John L. Sanders, "The North Carolina State House and Capitol, 1792-1972," unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State House Archives, 1972; John L. Sanders, "This Political Temple, the Capitol of North Carolina" (Popular Government, Fall 1977); Harry L. Watson, "'Old Rip' and a New Era" in Lindley S. Butler and Alan D. Watson, The North Carolina Experience: An Interpretive and Documentary History (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1984).

1John L. Sanders,"The North Carolina State House and Capitol, 1792-1972," unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State House Archives, 1972.

2 Ibid.

3 John L. Sanders, "This Political Temple, the Capitol of North Carolina" (Popular Government, Fall 1977), 1.

4Senate Reports of the Joint Select Committee on Public Buildings and Rebuilding the Capitol (Raleigh: State of North Carolina, 1841).

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Classical Precedents

Why did Americans of the early national period so admire the classical buildings of the ancient Romans and Greeks? In essence, they believed they were shaping a form of government which had not been seen since the time of the great Roman Republic when power resided with the Senate. By today's definition, a republic refers to a form of government in which the power resides with the voting citizens and is exercised by their chosen representatives. When the nation was first founded, however, republicanism meant much more: it rejected the idea of a monarchy, the form of government of Great Britain and most other nations of the time; and it held to the belief that liberty was more important than political power. The nation's founders believed a republic would balance liberty and power to the benefit of citizens. They saw close parallels between republican Rome and the United States. The buildings constructed by the Romans served as useful models for the architects of the new republic. These new buildings reflected what they believed to be Rome's greatness.

In 1762, Englishmen James Stuart and Nicholas Revett published The Antiquities of Athens, a book of sketches that eventually greatly influenced architecture in the United States. The authors had traveled to Greece and studied many of its ancient buildings. For many years, their sketches made little impact, however, because it was believed that Greece was just one of several imitators of the classical style created by Romans. However, new research demonstrated that classical forms actually had originated in Greece. Greece also was where the concepts of liberty and democracy had flourished. The Roman Republic, on the other hand, had given way to the brutal Roman Empire. Many people now began to accept the idea that ancient Greek architecture, with its emphasis on simplicity, symmetry, and balance, represented Greek ideas of government and, therefore, was appropriate for a nation that believed power belonged to the people, not to an individual ruler. The Neoclassical or Greek Revival Style based on the buildings of ancient Greece now was adopted by architects across the country for use in public buildings such as State Houses and courthouses. The Greek Revival Style dominated American architecture between 1820 and 1840.

As state governments became more confident in their abilities to manage public affairs, they wanted impressive buildings in which to govern. North Carolina was not to escape this wave of patriotic emotion spreading across the country. The main designers of the existing North Carolina capitol, Ithiel Town and Alexander Jackson Davis, used drawings found in Stuart and Revett's Antiquities of Athens. Most of the capitol's architectural details--columns, moldings, ornamental plasterwork, and anthemion (honeysuckle) crown on the dome--were carefully patterned after features of particular ancient Greek temples.

The North Carolina State Capitol in Raleigh has been a source of pride to North Carolinians for more than 150 years. Its attractive architectural style and high quality construction testified to the ambitions of a state that saw itself as somewhat of a backwater region. One view published in The Raleigh Star claimed that: "Henceforth our youth may never need to roam The arts to study, better seen at home."1

Questions for Reading 3

1. What publication influenced the popularity of Greek Revival architecture in America?

2. Do you think Greek Revival architecture was an appropriate style for public buildings in North Carolina and the rest of America? Why or why not?

3. Do you think many people in 1840 or today know of the specific Greek structures from which many design elements of the North Carolina State House were borrowed? Do you think knowledge of the Greek styles is necessary to appreciate the building? Why or why not?

Reading 3 was compiled from Russel Blaine Nye, The Cultural Life of a New Nation, 1776-1830 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960); John L. Sanders, "The North Carolina State House and Capitol, 1792-1972," unpublished manuscript, North Carolina State House Archives, 1972; and Jack Zehmer and Sherry Ingram, "Capitol" (Wake County, North Carolina) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1970.

1The Raleigh Star, 3 April, 1839.

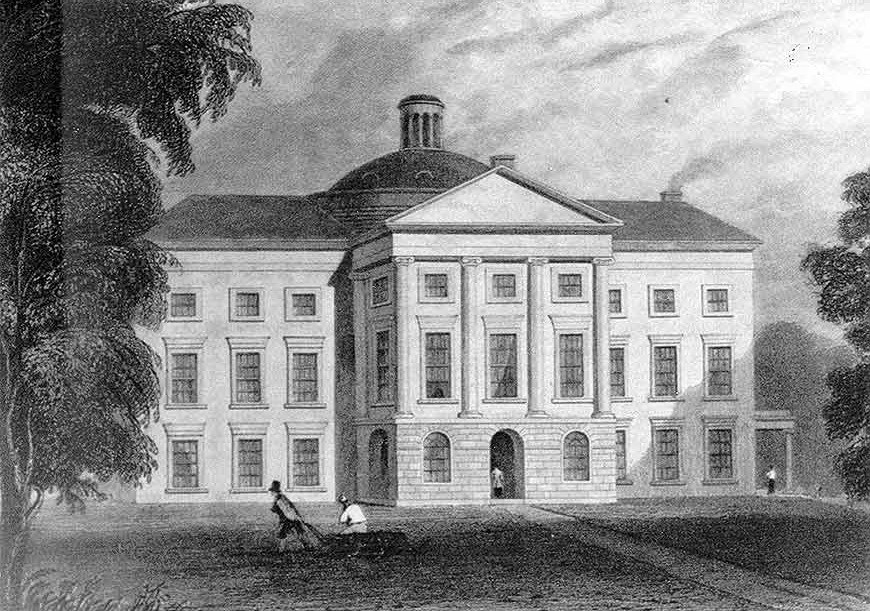

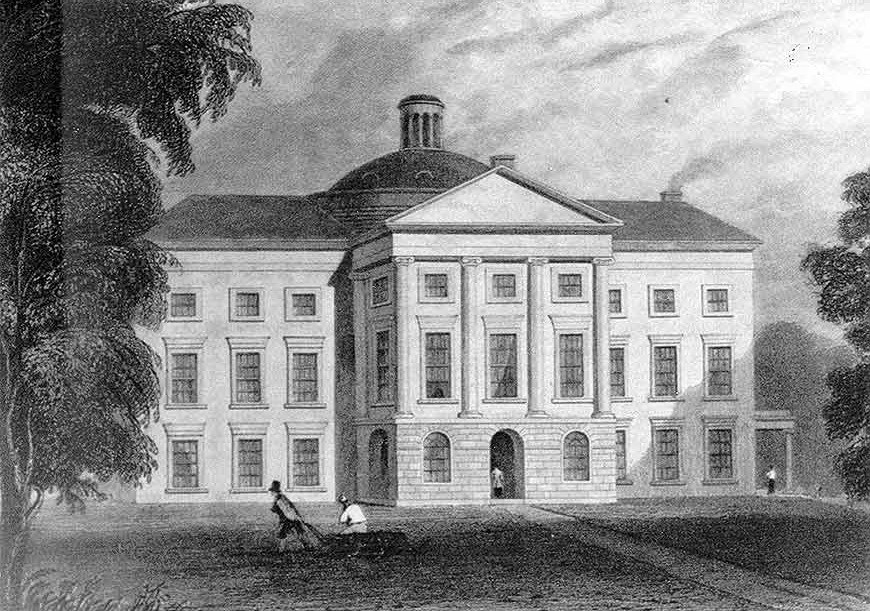

Drawing 1: The remodeled North Carolina State House by W. Goodacre.

Photo 1: The North Carolina State Capitol today.

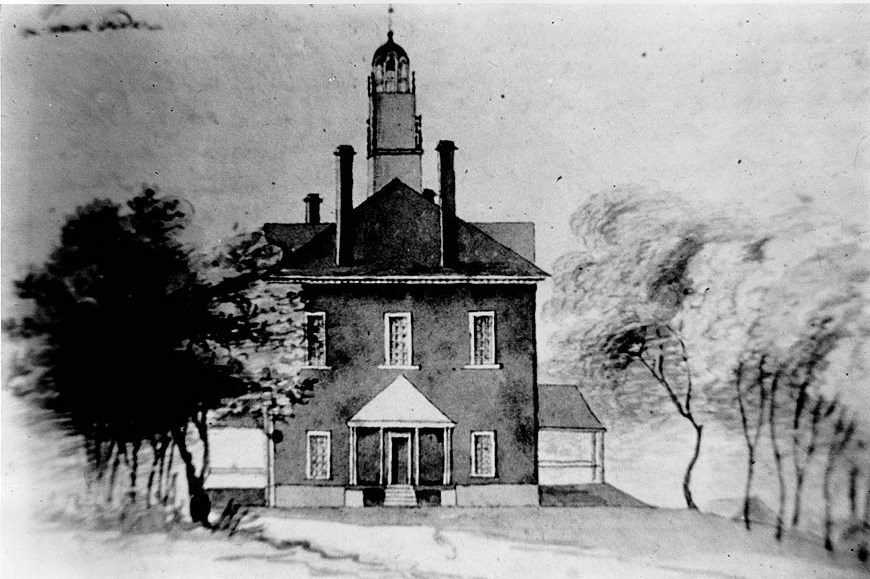

Questions for Painting 1, Drawing 1, and Photo 1

1. Compare the three versions of the North Carolina capitol. How would you describe each building?

2. What are some similarities and differences among the designs? Which building looks most like a State House to you? Why?

Visual Evidence

Photo 2: North Carolina State Capitol, House of Representatives.

Photo 3: North Carolina State Capitol, Senate Chamber.

Drawing 2: North Carolina State Capitol, second and third floor plans.

Visual Evidence

Photo 4: Statue of George Washington in North Carolina State Capitol.

(North Carolina Division of Archives and History, State Captiol)

Members of the North Carolina legislature appropriated $10,000 to hire Antonio Canova, then recognized as the world's best sculptor, to create a marble statue of George Washington for the State House. Sculpted in Italy and placed in the rotunda of the State House in 1821, this classical Washington, dressed in a tunic like a Roman soldier, was at first detested by many who thought the general should have been clothed in his military uniform. The statue soon came to be a source of pride for the citizens of the state, however. When the statue was destroyed in the fire of 1831, plans were immediately made to replace it and to have it placed in the new Capitol. However, not until 1970 was a copy made and placed in the Rotunda, where it stands today, a reminder of the Capitol's early classical influence.

Questions for Photo 4

1. Why might some people have found the statue offensive when it first was placed in the North Carolina State House in 1821?

2. Why do you think the sculptor thought it was appropriate to present George Washington in classical dress?

3. What do you think would be the reaction to a sculpture of a present-day politician in Roman or Greek attire?

Putting It All Together

The following activities will help students discover the history of their own state capitol as well as how architecture can reflect civic pride.

Activity 1: Locating a Capital

Working in small groups, have students research the towns in their state that seemed to have had a good chance to become the capital. (In some states, a better research topic would be competitions for particular county seats.) Ask the groups to pretend that they are responsible for locating the capital of the state (or the county seat). Using their research, have them present the group's findings to the class. After all suggestions have been offered, have the full class arrive at a decision as to where the capital (or county seat) will be located. If the class's choice is a place other than the current capital (or county seat), have student volunteers try to change the minds of the rest of the class.

Activity 2: A Proud Symbol

Have students work in groups to conduct research on the history of their state capitol building. They should try to discover who designed the building and when; what other designs were considered at the time; how and why the site was chosen; what architectural style the building represents; how citizens reacted to the design; and what changes have taken place to the building since it was completed. Next, have each group choose a capitol building from another state and compare it to their state capitol.

Activity 3: Classical Architecture in the Local Community

Arrange for students to take a walking tour in the community to see if they can find examples of the different features of Greek Revival architecture such as columns, friezes, pediments, etc. They may need to refer to a dictionary, encyclopedia, or other reference source to help them visualize these terms. When they find one of the features, students should sketch it as it appears on the building, write down the address of the building and, if possible, identify the building, its original use, and the year of construction. Some public buildings will have cornerstones that give the date of construction. To find the dates for other buildings, have students check with the Building Departments of local and county governments or work with the reference department of the public library. Hold a classroom discussion on why they think the buildings they found were designed in the Greek Revival Style.