When the Civil War began in 1861, there were over 4 million African Americans held in slavery. President Abraham Lincoln, sworn to uphold the Constitution which guaranteed slavery, carried out the war for the expressed purpose of saving the Union and preventing the fracturing of the nation. The issue of abolishing slavery was not something he readily embraced.

"If I could save the Union with the freeing of any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it. " Horace Greeley to President Lincoln

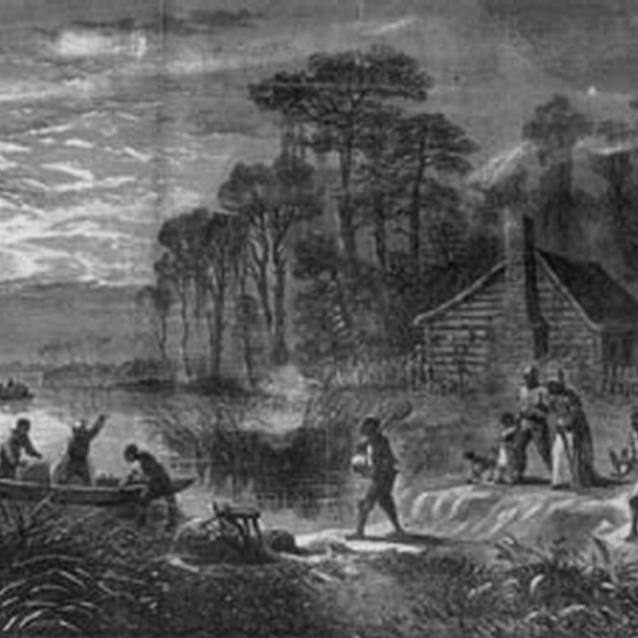

Running from Bondage

Library of Congress

As the war continued, increasing numbers of enslaved people began to flee from bondage; some escaping north, others seeking refuge with the Union army. Escaped slaves entering Federal lines were classified as "contraband of war" and kept in Union camps. Many were assigned jobs as cooks and laborers for the army. With no other plan prepared, Lincoln allowed the Contraband policy to go into effect.

After the failure of the Peninsula Campaign in the summer of 1862, Union morale was low. The northern economy was shaky, optimism for victory had faded, and Lincoln's Cabinet feared growing Confederate strength would encourage foreign intervention. Something needed to be done to rejuvenate northern enthusiasm. Having done little in the way of forming an emancipation policy, Lincoln began to see freeing slaves not as a constitutional dilemma or a moral choice, but as a way of regaining an advantage in the war. Great Britain and France could not join in an effort to preserve slavery in the South. Many northerners opposed emancipation unless it was done to deny the Confederacy the labor and support the slaves provided. Was this the time to make a stand, change the course of the war, and proclaim freedom for the slaves of the South?

Start of Political Action

Library of Congress

On August 19th, 1862, Horace Greeley, the influential editor of the New York Tribune, wrote an open letter to President Lincoln entitled "The Prayer of the Twenty Millions." In the letter, he chastised Lincoln, writing that he and his readers were, "sorely disappointed and deeply pained by the policy you seem to be pursuing with regard to the slaves of the Rebels."

Lincoln, already privately supportive of emancipation, had to respond to Greeley. His stern rebuke offered little insight into what the President was planning, but made clear that he was confident and determined to proceed on a path of his choosing. A year of war and strife had erased the timidity that marked Lincoln's first months in office. Here was a Commander-in-Chief ready with strong words and bold actions:

"My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union with the freeing of any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it. And if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about slavery and the colored race I do because I believe it helps to save the Union. And what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union."

Little did Greeley, or the rest of the country know, Lincoln had already been planning for a revolutionary change in his war policy.

Beginning in July, Lincoln drafted and edited an proclamation of emancipation. Convinced that new energy was needed to win the war and finally sure that the nation would support it, he shared the document with his Cabinet at a meeting on July 22nd. After a few minutes of shocked silence, the Secretaries gave their opinions. Most supported it, Secretary of Treasury Salmon Chase going so far as saying that it was not forceful enough and it did not mention arming the freed slaves. Only Postmaster General Montgomery Blair was against it; fearing what it would cost the administration politically. Secretary of State William Seward brought up a point Lincoln had not considered:

"Mr. President, I approve of the proclamation, but I question the expediency of its issue at this juncture. The depression of the public mind, consequent upon our repeated reverses, is so great that I fear the effect of so important a step. It may be viewed as the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help."

President Lincoln put aside his draft and waited for the right time to make his proclamation. With Union Gen. John Pope's Army of Virginia maneuvering across northern Virginia looking for an opportunity to strike the Confederates, it seemed that a decisive battle was imminent.

Part of a series of articles titled Born of Earnest Struggle.

Tags

Last updated: February 3, 2015