North and South divided. A country torn apart. We all know what followed the tumultuous break-up of the nation in 1860, but what did Abraham Lincoln, only just beginning his role as America's 16th president, have to say about the actions of the South and what the consequences could mean for the world?

"Secession would destroy the only democracy in existence and prove for all time - to both future Americans and the world - that a government of the people could not survive." Abraham Lincoln

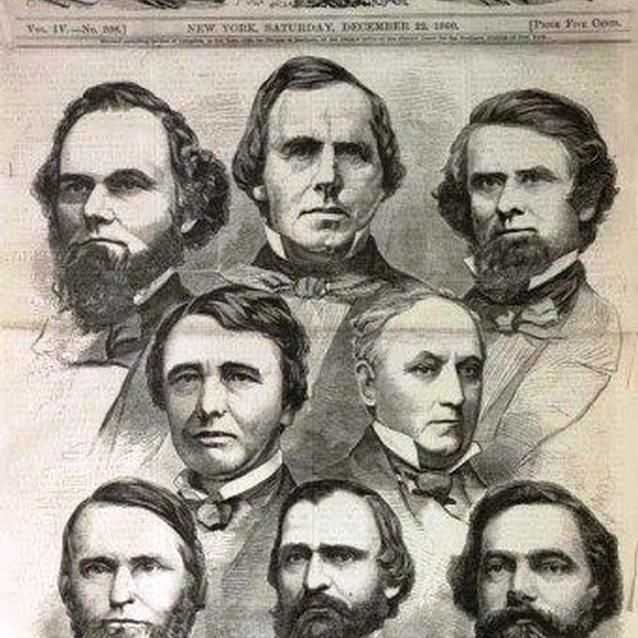

Library of Congress

It was just a month after Abraham Lincoln's winning of the White House in November 1860 when the frayed ties holding the country together finally broke loose. On December 20, increasingly angered by the fight over slavery and incensed over the election of an anti-slavery president, South Carolina defiantly declared that it was leaving the Union. Six more states followed a month later and, by June, a total of 11 southern states were no longer part of the country. The secessionists claimed that - according to the Constitution - they had every right to leave the Union, but Lincoln vehemently refuted that assertion.

He gave several reasons, among them his belief that secession was unlawful, the fact that states were physically unable to separate, his fears that secession would cause the weakened government to descend into anarchy, and his steadfast conviction that all Americans should be friends towards one another, rather than enemies. But it may have been the last point that he considered the most important to his argument: Secession would destroy the only democracy in existence and prove for all time - to both future Americans and the world - that a government of the people could not survive.

"Is there, in all republics, this inherent and fatal weakness? Must a government, of necessity, be too strong for the liberties of its own people, or too weak to maintain its own existence?" asked Lincoln of Congress on July 4, 1861.

He had good reason to raise the question, for if you traveled the earth in 1860 and visited every continent and nation, you would have found many examples of monarchies, dictatorships, and other types of authoritarian rule. But all of the world over, you would have found only one major democracy: the United States of America. Democracy had been attempted in only one other nation during the 18th century - France - and the results not been successful.

With its citizens fonder of voting through the guillotine than the ballot box, France's radical experiment in self-government did not last long, and when Napoleon rose from the ashes of the disaster and went on a quest to conquer all of Europe, monarchy supporters felt thoroughly vindicated. Yet the United States' seemingly successful democratic rule remained a pesky thorn in their side. After all, those wishing for more political freedom could still point across the ocean and say, "It works there. Why can't we try it here"?

With the dissolution of the United States in 1860, however, it appeared that the thorn was finally being removed. Monarchists were thrilled and many even held parties celebrating the end of democracy. Lincoln understood this well, so when he described America as "the world's last best hope," the words were not idle ones. Lincoln truly believed that if the Civil War was lost, it would not only have been the end of his political career, that of his party, or even that of his nation - it would have forever ended the hope of humankind everywhere for a "government of the people, by the people, for the people."

Last updated: February 3, 2015