Last updated: February 24, 2023

Article

Patriotism and Prejudice: Japanese Americans and World War II

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Park Archives

One of the most poignant and sadly ironic home front stories of World War II has deep connections to the Presidio. Even as Presidio officers issued orders to relocate Americans of Japanese ancestry to concentration camps after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December, 1941, a secret military language school trained Japanese American soldiers only a half mile away. The loyalty, sacrifice, and triumphs of the Japanese American soldiers trained at the Presidio and elsewhere were recognized at the highest levels, but their families had to endure a very different sacrifice as the army moved them to camps far from home.

National Archives and Records Administration

Military Intelligence Service Language School at the Presidio

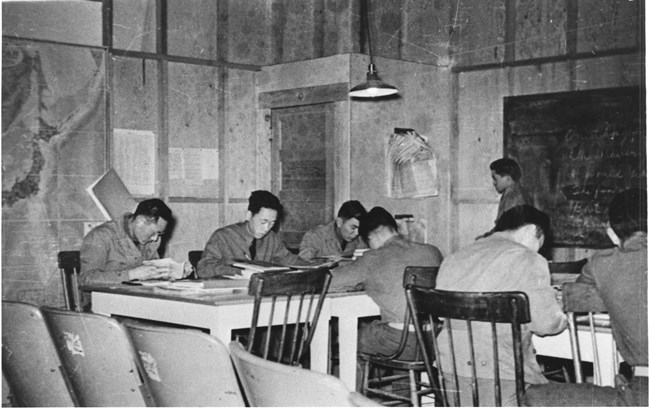

During the 1930s, the deterioration in the diplomatic relations between the United States and Japan signaled the possibility of war. As a result, the U.S. Army established the 4th Army Intelligence School at the Presidio of San Francisco in November of 1941. The army converted hangar Building 640, on Crissy Field, into classrooms and a barrack for a language school which trained Nisei – Japanese Americans born to parents who had come to the U.S. from Japan – to act as translators in the war against Japan. Although this secret training program was planned to last a year, the program was shortened to 6 months after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7.

The soldiers trained at the Presidio MIS were then sent to all the major battlefields in the Pacific. The MIS Language School moved to a more secure inland location in Minnesota after the first class graduated. The 6,000 graduates from the school went on to work with combat units interrogating prisoners, translate intercepted documents, and to use their knowledge of Japanese culture to assist the U.S. occupation after the war. General Douglas MacArthur’s chief of staff said, “The Nisei [graduates of the MIS Language School] saved countless Allied lives and shortened the war by two years.”

National Archives and Records Administration

Incarceration

While the Japanese American soldiers trained at the Presidio MIS Language School, anti-Japanese sentiment throughout the United States grew after the bombing of Pearl Harbor and war hysteria escalated. At the Presidio of San Francisco, Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, wrote to Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, referring to Japanese Americans as ‘potential enemies’ and requiring the exclusion of Japanese Americans on the West Coast out of ‘military necessity’. After Stimson relayed General DeWitt’s suggestions to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The order authorized the War Department to designate military zones where persons of ‘enemy’ ancestry would be excluded. At the Western Defense Command headquarters in the Presidio, General DeWitt signed the 108 Civilian Exclusion Orders and directives that enacted Roosevelt’s order across the West Coast. One of many detention camps was soon opened at Sharp Park near Mori Point, now part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

By the fall of 1942, all Japanese Americans had been evicted from California and relocated to one of ten concentration camps built to imprison them. Prohibited from taking more than they could carry into the camps, many people lost their property and assets as it was sold, confiscated or destroyed in government storage. As four or five families with their sparse possessions squeezed into and shared tar-papered barracks, life consisted of some familiar patterns of socializing and school. However, eating in common facilities and having limited work opportunities interrupted other social and cultural routines. Persons who were deemed ‘disloyal’ were sent to a segregation camp at Tule Lake, California. When World War II drew to a close, the camps were slowly evacuated and no person of Japanese ancestry living in the United States was ever convicted of any serious act of espionage or sabotage.

Library of Congress, Ansel Adams

The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco reported these citizens had suffered $400 million dollars in losses. The internment of persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II sparked great constitutional and political debate. Nearly 40 years later, the federal government formally acknowledged that “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership” motivated this mass incarceration—not “military necessity.” During the Reagan-Bush years Congress moved toward the passage of The Civil Liberties Act in 1988 which acknowledged the injustice of the internment, apologized for it, and provided $20,000 to each person surviving the incarceration camps as a means of reparations.

Tags

- presidio of san francisco

- japanese american

- world war ii

- presidio

- internment camps

- pearl harbor

- military language school

- japan

- soldiers

- crissy field

- nisei

- mis

- john l. dewitt

- fdr

- franklin d roosevelt

- executive order 9066

- the civil liberties act in 1988

- site of conscience

- japanese american incarceration

- wwii home front

- aapi

- aapi history

- california

- civil rights

- spies

- pacific

- us army