Last updated: March 30, 2023

Article

Paterson, New Jersey: America's Silk City (Teaching with Historic Places)

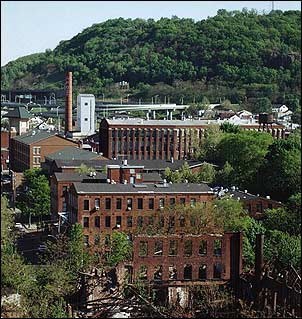

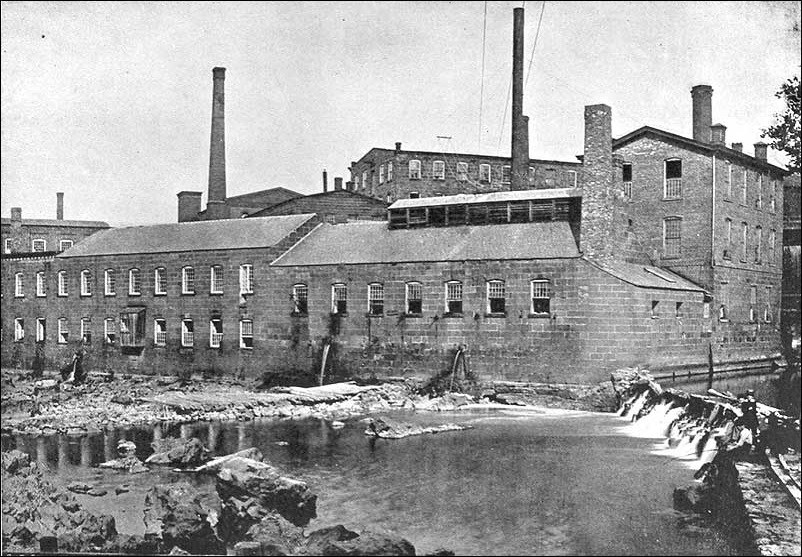

The water cascades over rugged cliffs, drops 77 feet, and rushes through the Passaic River Gorge. Paterson, New Jersey was established in the 1790s to utilize the power of these falls. Massive brick mill buildings lined the canals that transformed the power of the falls into energy to drive machines. These mills manufactured many things during the long history of this industrial city--cotton textiles, steam locomotives, Colt revolvers, and aircraft engines. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, they produced silk fabrics in such quantities that Paterson was known as "Silk City." In 1913, however, the mills stood silent for five months as workers joined in a bitter strike that brought the city national attention.

The suburban house where leaders of the radical Industrial Workers of the World rallied thousands of workers on Sunday afternoons still stands. The elaborate home of one of the mill owners still looks down over the city from its prominent position on the side of Garret Mountain. Many of the mill buildings also survive, mute witnesses to a turbulent history.

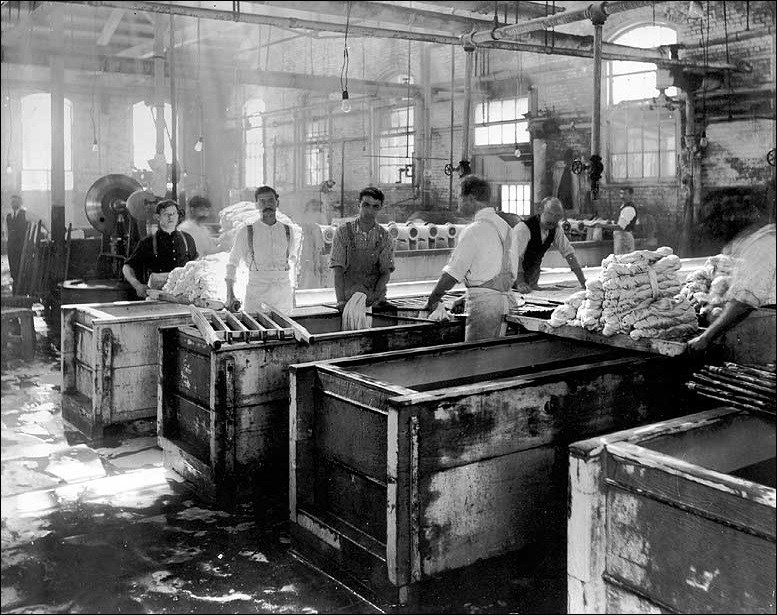

What type of work do you think is being performed in this photo?

Setting the Stage

The early 20th century was a time of increased conflict between labor and management throughout the United States. From the textile mills of the Northeast, to the steel mills and factories of the Midwest, to the mines and lumber camps of the Rocky Mountain West, thousands of workers all over the country walked picket lines. According to one source, there were at least 1,800 work stoppages a year at the turn of the century and as many as 2,000 a year in 1910.¹ One of the most famous strikes occurred in Paterson, New Jersey, in 1913, when more than 20,000 silk workers joined in an industry-wide strike that lasted more than five months.

Silk was a relative latecomer in Paterson's long industrial history. The city had been established during the great debate of the 1790s between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson and their allies about industrial development. Hamilton encouraged the creation of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (S.U.M.), a private corporation that selected the Great Falls of the Passaic as the location for an industrial city in 1792. By 1794 the S.U.M. had completed the first of a series of canals to harness the power of the falls for industrial use. When the first "manufactory" failed in 1796, the S.U.M. abandoned manufacturing to become a real estate and energy broker, leasing water power and land to private entrepreneurs, inventors, and industrialists into the post World War II era.

Silk was first manufactured in Paterson in 1840, but did not prosper until after the Civil War, when high tariffs on imported silk products helped American producers compete with their European rivals. Silk manufacturing was a big business before the days of synthetics. Silk, the "queen of fibers," dominated high fashion and the luxury trade, but women at all economic levels wanted their "best dresses" to be silk. Paterson had many advantages for the silk trade. It had abundant water supplies for power and processing and good transportation facilities. It also was close to New York City, the center of the fashion industry. Most importantly, Paterson had a supply of workers who understood the peculiar characteristics of the delicate silk fiber. By the 1880s, the city was producing almost half of the silk manufactured in the United States and had earned a nationwide reputation as "Silk City."

¹Bernard Bailyn, Robert Dallek, et al. The Great Republic (D.C. Heath and Company, 1981), 611.

|

|

Questions for Map 1

1. Identify the Passaic River. Paterson is located at the Great Falls of the Passaic, where the river cuts through the edge of the Wachung Mountains and drops almost 80 feet. Why would this location have appealed to men looking for an industrial site at the end of the 18th century?

2. Note the distance between New York City and Paterson. New York was the center of the fashion industry, the port of entry for imported raw silk, the nation's leading capital market, and the embarkation point for thousands of immigrants. How do you think Paterson's proximity to New York affected its success as a silk manufacturing center?

(Published with permission of Department of Community Development, Paterson, NJ)

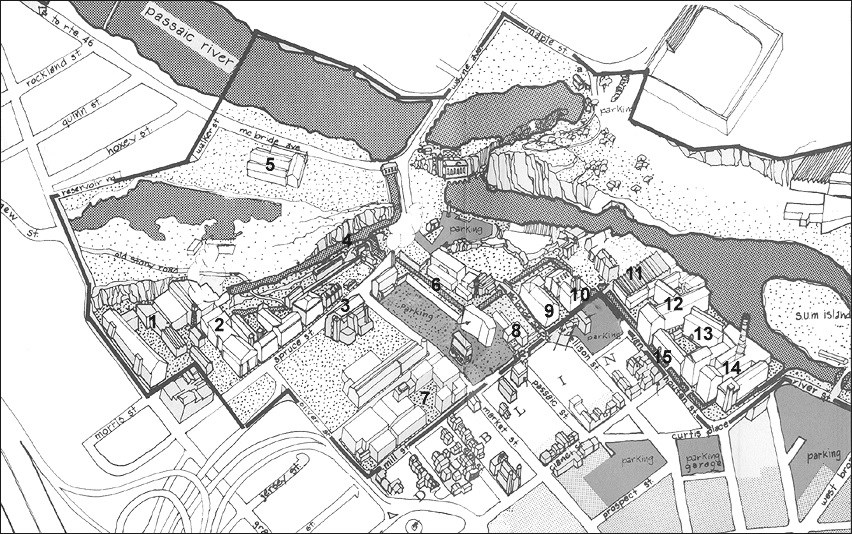

Key to Map 2:

1. Barbour Flax Spinning Company Complex, 1860-1881. One of the largest linen works in the U.S. in the late 19th century.

2. Dolphin Mill Complex, 1844, 1869. Initially spun hemp into rope, later produced jute carpeting.

3. Rogers Locomotive Company Complex, 1871-1881. The largest of three locomotive plants in Paterson in the late 19th century. Continued in operation until 1926.

4. S.U.M. Upper Raceway, 1827-1846.

5. Casper Silk Mill, 1900-1915.

6. S.U.M. Middle Raceway, 1792-1802.

7. Cooke Locomotive Company Complex, 1830s, 1881.

8. Hamilton Mill, includes remains of first S.U.M. cotton mill. Used for silk weaving and throwing in the 1910s. Damaged by fire.

9. Franklin Mill, ca. 1870, ca. 1920. Built as a cotton mill, later used to produce machinery, steam fire engines, locomotives. Housed a foundry and silk weaving in the 1910s.

10. Essex Mill, 1850s, 1870s. Incorporates portion of 1803 Old Yellow Mill used for experiments in manufacturing paper in continuous sheets. Later produced silk mosquito netting. Used for silk weaving in the 1910s.

11. Allied Textile Printers Complex, 1836 with many later additions. The first Colt revolver was manufactured in the 1836 Gun Mill building. Experiments in producing silk were begun here in 1838. John Ryle, the first to manufacture silk successfully, operated a silk works in the building from 1840 to his death in 1887. In the 1910s, most of the complex housed one of Paterson's largest silk dye works. Other buildings were used for silk weaving. The complex was seriously damaged by fire in the 1980s.

12. Congdon Mill, ca. 1915. Used by various silk manufacturers.

13. Phoenix Mill, ca. 1813, 1826-27, 1880. Originally a cotton mill, was used for silk beginning in the 1860s. Also manufactured silk-processing equipment. Used for silk weaving in 1910s.

14. Harmony and Industry Mills, 1876, 1878-79. Harmony Mill initially used for cotton. Both mills owned by William Adams and Co., silk manufacturers. Used for silk dyeing and weaving in 1910s.

15. S.U.M. Lower Raceway, 1807.

Questions for Map 2

1. Using the key, examine Map 2 carefully. Locate the upper, middle, and lower raceways. These canals carried water from the falls to the mills. Turbines and gears converted it into power to operate machinery. The S.U.M. expanded the raceways as the needs of manufacturers for land and water rights grew. The mills along the raceways continued to use water power until the early 20th century. Why might they have used water power after steam, electricity, and other sources of power became available? Why would this have been a profitable operation for the S.U.M.?

2. How many different industries were located in the mills in the historic district? How many of the mills were used for silk?

3. Locate the area marked "Dublin." Many of the houses in this area date from the early 19th century. Both owners and workers lived in Dublin during that period. Why do you think that was the case? By the early 20th century, those who could afford to had moved out to the suburbs, which could now be reached by streetcar. Why do you think people would have wanted to move out of the city if they had the opportunity?

Determining the Facts

Reading 1: Working "In the Silk"

Silk is a natural fiber taken from the cocoons of the silk worm. The silk fibers are so fine that a single pound might measure 1,000 to 1,500 miles or even more. All raw silk used in Paterson was imported, principally from China, Japan, and Italy. The process of producing silk fabrics was divided into four stages: throwing (twisting the silk fibers into threads strong enough to be used in the looms), dyeing, weaving, and finishing. In 1913, Paterson dominated the weaving of high quality broad silk and ribbon.¹

Paterson's share in the silk dyeing industry was expanding. In the dye houses, workers dipped skeins (length of thread wound in a loose long coil) of silk thread and pieces of fabric into large vats of hot chemicals. Almost all of the workers were men. Master dyers, many from traditional silk centers like Lyons, France, or Como, Italy, were highly skilled craftsmen. Dyers' helpers were generally unskilled and low paid. Italian dye house workers had a reputation for being political radicals.

In Paterson's ribbon and broad silk weaving factories, the delicacy and high cost of the fiber and the value of the end product defined the work, the working conditions, and the relations between the workers and the owners. Weavers were skilled workers. Most were immigrants, often from traditional silk textile areas in England, Germany, and Italy. Nearly half were women, but men dominated the best paying jobs. Children began work at about age 14 and might spend the rest of their working lives "in the silk." They could expect to move up to skilled jobs like weaver or loom fixer or even, in rare cases, independent manufacturer. Workers who wanted to set up in business for themselves did not need much money to rent space in the old mills along the S.U.M. raceways. Plenty of skilled labor was available, and the new owners themselves could provide the necessary experience and expertise.

The working day was 10 hours long by 1913, with a half day on Saturday. Wages were well below the average for industry as a whole. Many workers preferred working in the silk mills to other employment, however. Because the products were so valuable, the mills were generally clean. The silk threads had to be watched carefully to detect and correct problems, so good lighting was critical. New mills, located all over Paterson by the early 20th century, were carefully designed to provide the necessary natural light. Their machinery was well protected and spaced to allow the workers to move around in safety.

In spite of the owners' efforts to reduce silk weaving to a series of simple tasks that could be performed by unskilled workers, many operations involved a high proportion of hand work that depended on the skill of the individual worker. In testimony submitted to a Congressional committee, a silk manufacturer from Connecticut reported:

The hands of the silk worker are one of his most important assets. . . . Machinery does not do away with the use of hands in silk manufacture. The hands still remain, and will always remain, in my opinion, a very important factor in the operation. A man with clumsy, awkward hands handling silk warp is a very different factor from the man whose grandfather before him handled the silk fabric.²

Conflict between labor and management was common in Paterson's silk industry. Between 1881 and 1900 there were nearly 140 strikes. Many silk workers came from countries with long traditions of commitment to the working class and willingness to confront management to improve working conditions. Although they did not form permanent unions, they organized effectively at the factory level to defend themselves against changes in traditional work practices, to resist wage reductions in hard times, and to demand raises when sales were up. In most early strikes the workers enjoyed support throughout the community. It was the workers who elected the city officials and who were friends or relatives of the police, customers of the merchants, and members of the churches.

By the first decade of the 20th century, practically every broad-silk and ribbon-silk mill had one or more labor organizations. A 1911 government survey of the silk industry credited organized labor in Paterson with achieving the 55-hour week and delaying the introduction of the four-loom system that was already common in new mills elsewhere in the country.

Beginning in the 1880s, Paterson's owners began moving some of their operations to Pennsylvania, in part to avoid labor disputes. Reacting to increased competition, they tried to change work rules that had been accepted for a generation. They used differences of gender, ethnicity, skill, and ideology to keep workers divided. An enlarged and strengthened police force began to see labor protest as a threat to established society. Violence, discrimination against Italians and other recent immigrants, and repression of radicals increased. By 1913, the old ways of settling disputes between the workers and the owners were no longer working.

Questions for Reading 1

1. What were the major steps in silk production? Why would the mill owners want to break the process down into so many separate steps? How might that have affected the workers?

2. How would you describe working conditions in the silk industry? In what ways was working in a silk mill better than working in other industries?

3. What did the workers hope to gain from their frequent strikes?

Reading 1 was adapted from John A. Herbst and Catherine Keene, Life and Times in Silk City (Haledon, NJ: The American Labor Museum, 1984); Philip Scranton, ed., Silk City, Studies on the Paterson Silk Industry, 1860-1940 (Newark: New Jersey Historical Society, 1985); U.S. Senate, Report on Condition of Woman and Child Wage-Earners in the United States, Vol. IV: The Silk Industry (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1911); National Industrial Conference Board, Hours of Work as Related to Output and Health of Workers: Silk Manufacturing, Research Report No. 16 (Boston, Mass.: 1919); and James Sheire, "Pietro Botto House" (Passaic County, NJ) National Historic Landmark Documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982.

¹ Fabrics 12" or more in width were classified as broad silk, used primarily for clothing and home decoration. Fabrics under 12" wide were classed as ribbon goods and were used for trim in hats, clothing, and decorating.

² National Industrial Conference Board, Hours of Work as Related to Output and Health in Workers: Silk Manufacturing, Research Report No. 16 (Boston, MA: 1919), 20.

Determining the Facts

Reading 2: Strike!

On January 27, 1913, 800 broad silk weavers walked off the job at the Henry Doherty plant, one of Paterson's largest and most modern silk mills. Their grievance centered on Doherty's extension of the four-loom system in broad silk throughout the mill. Doherty's new looms were equipped with automatic controls that stopped the machinery whenever a thread broke. This technological improvement made it possible for one weaver to tend three or four looms, instead of the customary two. Claiming competition from low wage silk mills in Pennsylvania and the South, Doherty said he had turned to the four-loom system to increase productivity and thus save jobs. He refused to discontinue the system for which he invested a great deal of money.

The broad silk weavers were soon joined by the ribbon weavers and the dye house workers. Soon after the strike started, the local representative of the Industrial Workers of the World union sent out a call to national headquarters requesting help in organizing the strike. The IWW, usually called the "Wobblies," advocated the formation of unions that included all workers in an industry, whether skilled or unskilled, and openly rejected the capitalist system. The union had earned a reputation for militant radicalism, even among other union organizers. "Big Bill" Hayward, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Carlo Tresca, and other famous IWW leaders arrived in Paterson in mid-February. They helped organize a central strike committee to unite the various craft and ethnic groups.

Committees were established to handle communications, to manage a strike relief fund, to provide legal help for arrested strikers, and to organize mass meetings. By the end of February, nearly 300 mills and dye houses were closed, as 24,000 men, women, and children joined in an industry-wide strike.

The strike immediately divided the Paterson community. On the one side were the mill owners and managers, the mayor, the chief-of-police, the judiciary, the clergy, the local press, and most of Paterson's middle class professionals and merchants. On the other side were the workers led both by their own people and by the IWW militants. The battle lines were drawn. This polarization was a major factor in the extraordinary length of the strike.

The strikers' demands were radical for the times. They included the abolition of the three- and four-loom system in broad silk and the two-loom system in ribbon weaving; wage increases for broad and ribbon weavers, dyers' helpers, and other workers; and the eight hour day. To achieve these demands, the workers relied on maintaining industry-wide unity. They agreed that no one would return to work until all of the owners accepted their terms. Picket lines kept strike breakers out of the mills and intimidated those who did go back to work. More than 2,000 workers allowed themselves to be arrested, flooding the jails. Mass meetings informed the workers of strike developments, quelled rumors, and boosted morale. Dramatizing the arrests of prominent IWW leaders and the funeral of a bystander shot by one of the private security guards hired by the owners helped maintain the solidarity of the strike, the commitment of all the workers to the common cause. A pageant in Madison Square Garden in New York City, organized by workers, IWW organizers, and sympathetic Greenwich Village intellectuals, attracted national attention.

The strike was remarkably free of violence. "Your power is in your folded arms," Haywood said. "You have killed the mills; you have stopped production; you have broken off the profits. Any other violence you may commit is less than this, and it will only react upon yourselves."¹

The mill owners refused to talk to the union. They tried to set old and new immigrants against each other and worked with police and the courts to forbid speeches and rallies by the strikers. "Solidarity, unconquered, unconquerable," the IWW's battle cry, also became the mill owners' primary tactic. They formed a manufacturers' association whose purpose was clear; the mill owners would stand united. The owners agreed that the best way to break the strike was to hold out until the harsh reality of empty stomachs and crying children forced the workers to answer the mill whistle. They farmed out what work they could to their Pennsylvania mills and waited.

By the end of May 1913, the workers' solidarity began to crack. The English-speaking and better paid workers were the first to break. They instructed their representatives on the central strike committee to vote to accept settlements with individual mill owners. At the same time workers started to cross the picket lines, despite the pleas of the IWW leaders. In July the central strike committee voted to endorse shop-by-shop settlements. The Paterson silk strike was over. The owners had conceded nothing. According to some estimates, the workers lost $5 million in unpaid wages during the strike and the mill owners lost $10 million in profits.

There is still debate about the effects of the strike. Although the owners agreed to none of the strikers' demands, the two-loom system was still the standard in Paterson in 1919. The strike certainly accelerated the transfer of Paterson's large-scale silk manufacturing to Pennsylvania that had begun in the 1880s. There is no debate on the effect of the strike on the IWW. The defeat in Paterson marked the end of the union's effectiveness in the East.

Paterson's silk industry did not stop growing after the strike, although its share of national silk production fell. Stimulated by wartime demand, it reached peak employment in 1919. Although hard hit by the Great Depression, a 1939 guide to New Jersey could still report that Paterson was the largest single silk-producing center in the country. By this time, the whole silk industry was in decline. The reasons given in the report were antiquated mills, the replacement of large mills with small family-operated shops, and the introduction of artificial silk (rayon).²

Questions for Reading 2

1. What role did the IWW play in the strike?

2. What was the immediate cause of the strike? What changes did the workers demand?

3. Who do you think "won" the strike? What were its effects?

4. What factors contributed to the decline of the silk industry in Paterson? Do you think the decline might have been prevented if the outcome of the strike had been different? Why or why not?

Reading 2 was adapted from James Sheire, "Pietro Botto House" (Passaic County, NJ) National Historic Landmark Documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982.

¹ Frederick S. Boyd, "The General Strike in the Silk Industry," in The Pageant of the Paterson Strike (New York: The Success Press, 1913), 5.

² Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of New Jersey, New Jersey: A Guide to Its Present and Past (New York: Hastings House, 1939 [1959 reprint]), 354.

Determining the Facts

Reading 3: Owners and Workers

Catholina Lamber, Owner

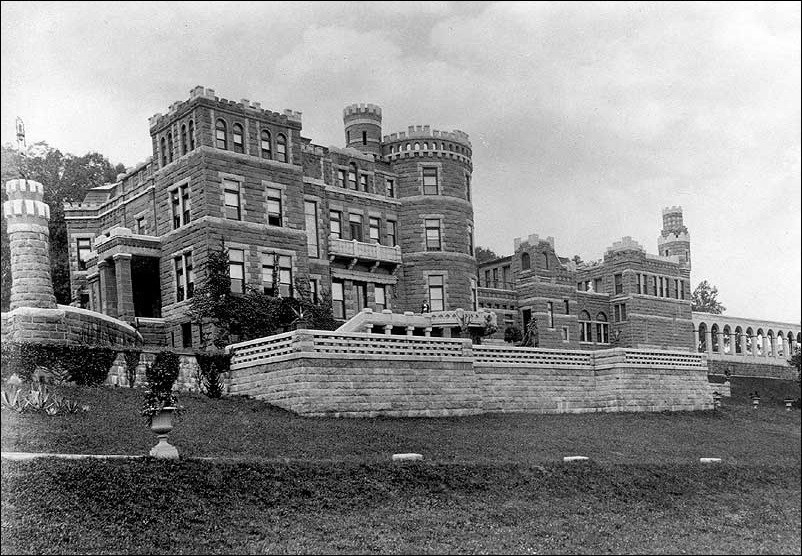

Most people regarded Catholina Lambert as one of the leaders of the manufacturers in the 1913 strike. The son of paper mill workers in Yorkshire, England, Lambert began work in a cotton mill at the age of 10. As a young boy, he reportedly read somewhere that "one out of 10 succeeds in England, nine out of 10 in America."¹ In 1851, at the age of 17, Lambert left England and found work as a bookkeeper in a Boston textile firm. Four years later he became a partner in the firm; within another three years he was head of the company and relocated many of its interests to Paterson. During the 1860s and 1870s, Dexter, Lambert & Co. prospered, growing into one of Paterson's most important silk manufacturers. In 1880 Lambert was one of the first to move some of his operations to an "annex" in Pennsylvania. Lambert also developed connections with suppliers of raw silk in Italy, increasing his control of the entire process of silk manufacture.

In 1892, Lambert built a new house high on the side of Paterson's Garret Mountain. The house was called Belle Vista, "Belle" in honor of his wife Isabelle and "Vista" for the spectacular view of the Manhattan skyline from its terrace. He gradually filled the mansion with more than 400 paintings, including works by Renoir, Monet, and Rembrandt. As his business grew and prospered, Lambert added a greenhouse and opulent gardens and built an observatory tower on the top of the mountain. In 1896 he added a new gallery to display his art collection.

Lambert was adamantly opposed to dealing with the strikers. When Henry Doherty, in whose mill the strike had started, was prepared to agree to a settlement with the workers, the 79-year-old Lambert confronted him angrily at a manufacturers' meeting and reportedly had to be restrained from physically attacking him.²

Despite his large income, Lambert had spent so lavishly that he could not recover from the strike. He suffered a further blow when the outbreak of World War I disrupted the businesses he owned in Italy. Lambert was forced to mortgage his property, auction off his art collection, and eventually sell one of his mills. He refused to retire, although he cut back his usual working day from 16 hours to 12. Proudly reporting that he had paid all of his debts, he lived at Belle Vista until his death in 1923. By that time, Dexter, Lambert, and Company was out of business.

Pietro Botto and Other Mill Workers

Pietro Botto's role in the strike was very different. Botto and his wife Maria, northern Italian immigrants, arrived in Union City, New Jersey, in 1892 where Pietro, a weaver, quickly found work in the silk mills. Maria Botto worked at home as a "picker," a skilled worker who examined finished fabric for flaws. By 1907 the family had saved and borrowed enough money to buy land and build a house in Haledon, a new suburb north of Paterson where many of their fellow Italians had settled. The family lived in the six first-floor rooms of the house and rented out two three-room apartments upstairs. During the week, Maria Botto cooked for boarders whose families were still in Italy. When Haledon became a popular resort area, the Botto house served as an informal inn. The backyard contained a bocci (and Italian game similar to lawn bowling) court and card tables for paying guests, and Maria and her four daughters cooked for as many as 100 visitors on a typical Sunday.

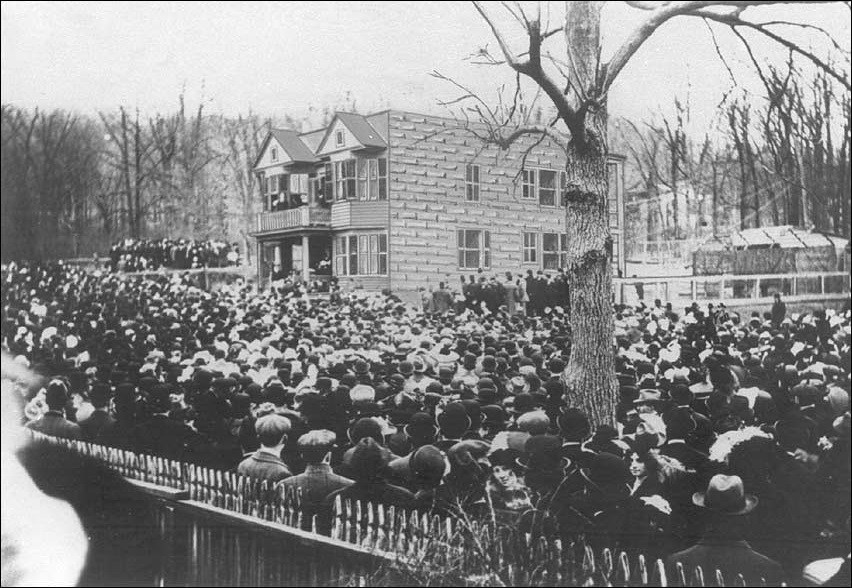

From April to June, 1913, the house played an important part in the silk strike. The socialist mayor of Haledon invited the strikers to the suburb. Although Pietro Botto was not a member of the IWW, he offered his home as a meeting place for the strikers and the Wobblies' leadership. IWW leaders Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Big Bill Haywood, and Carlo Tresca addressed the strikers from the home's second-story balcony. Perched on a hillside and surrounded by open land, the Botto House was a perfect location for the Sunday rallies that were so important in maintaining morale through the long months of the strike. Looking back many years later, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn remembered the Haledon meetings vividly:

There was a balcony on the second floor, facing the street, opposite a large green field. It was a natural platform and amphitheater. Sunday after Sunday, as the days became pleasanter, we spoke to enormous crowds of thousands of people--the strikers and their families, workers from other Paterson industries, people from New Jersey cities, delegations from New York, trade unionists, students and others. Visitors came from all over America and from foreign countries. People who saw those Haledon meetings never forgot them.³

Pietro Botto never again worked in the silk industry. One of his daughters even had to change her name to get a job.

We know about Pietro Botto's life because of his role in the 1913 silk strike. It is more difficult to reconstruct the lives of anonymous unskilled workers in the silk mills and dye houses. We know that unskilled workers in Paterson earned about half what weavers earned. Few families owned their own homes. Renters' quarters were generally smaller than the Bottos' and often housed boarders and roomers in addition to family members. Finally, most of Paterson's silk workers still lived in old, crowded, increasingly dilapidated residential areas like Dublin. The support of these ordinary workers was critical to the effectiveness of the strike and their willingness to endure five months without pay testified to their commitment.

Questions for Reading 3

1. In what ways is Catholina Lambert's life a "rags to riches" story?

2. Why do you think Lambert built a house like Belle Vista?

3. What role did Lambert play in the strike of 1913? Why do you think he was so opposed to Henry Doherty's reaching a settlement with the workers? Lambert had gone to work in the mills as a 10-year-old boy. How might that have affected his position?

4. How did the Bottos support themselves?

5. Why do you think Pietro Botto offered his house to the strike leaders, even though he was not a member of the IWW?

Reading 3 was adapted from D. Stanton Hammond, "Belle Vista" (Passaic County, New Jersey) National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973-74; Flavia Alaya, Silk and Sandstone: The Story of Catholina Lambert and His Castle (Paterson, NJ: Passaic County Historical Society, 1984); James Sheire, "Pietro Botto House" (Passaic County, New Jersey) National Historic Landmark Documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982; John A. Herbst and Catherine Keene, Life and Times in Silk City (Haledon, NJ: The American Labor Museum, 1984); and U.S. Senate, Report on Condition of Woman and Child Wage-Earners in the United States, Vol. IV: The Silk Industry (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1911).

¹ Flavia Alaya, Silk and Sandstone: The Story of Catholina Lambert and His Castle (Paterson, NJ: Passaic County Historical Society, 1984), 3.

² Alaya, Silk and Sandstone, 21.

³ Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, The Rebel Girl, My First Life: 1906-1926 (New York: International Publishers, 1973), 165; cited in James Sheire, "Pietro Botto House" (Passaic County, New Jersey) National Historic Landmark Documentation, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1982, Section 8, p. 15.

Visual Evidence

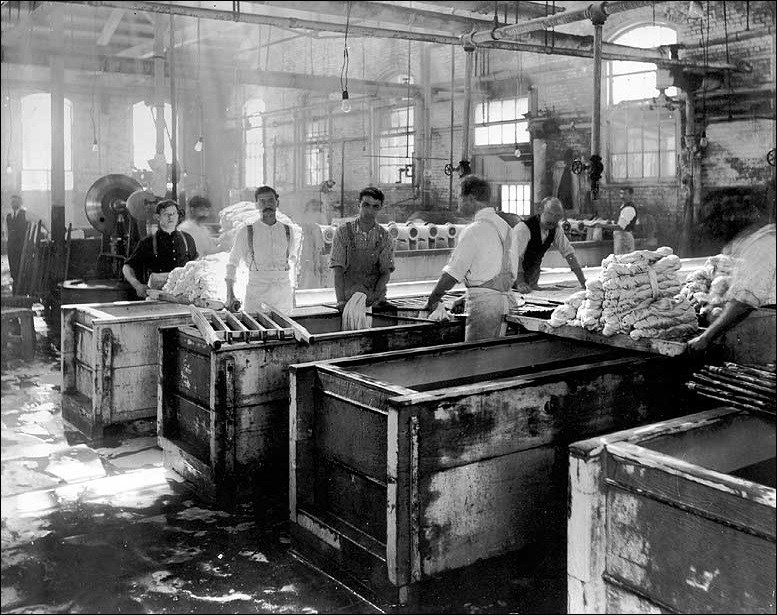

Photo 1: Dye House in the Great Falls/S.U.M. Historic District, ca. 1910.

(National Park Service, Reid Studios, photographer)

Photo 1 shows one of Paterson's large dye houses. Notice the water running out of drains in the building. The soft water of the Passaic River was supposed to be particularly good for dyeing.

Photo 2: Dye house workers, ca. 1900.

Photo 2 shows the interior of a dye house. The vats contained hot water and chemicals into which the skeins of silk thread were dipped.

Questions for Photos 1 and 2

1. Study Photo 1. How much light do you think the windows would provide to the interior of the building? Why was this important?

2. Based on Photos 1 and 2, what do you think working in a dye house would have been like?

3. What can you learn about the time period by studying Photo 2?

Visual Evidence

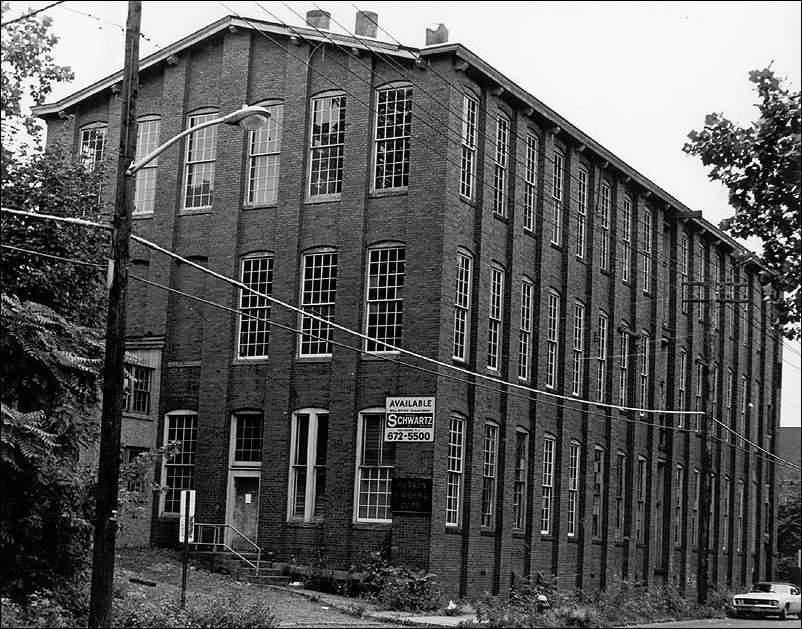

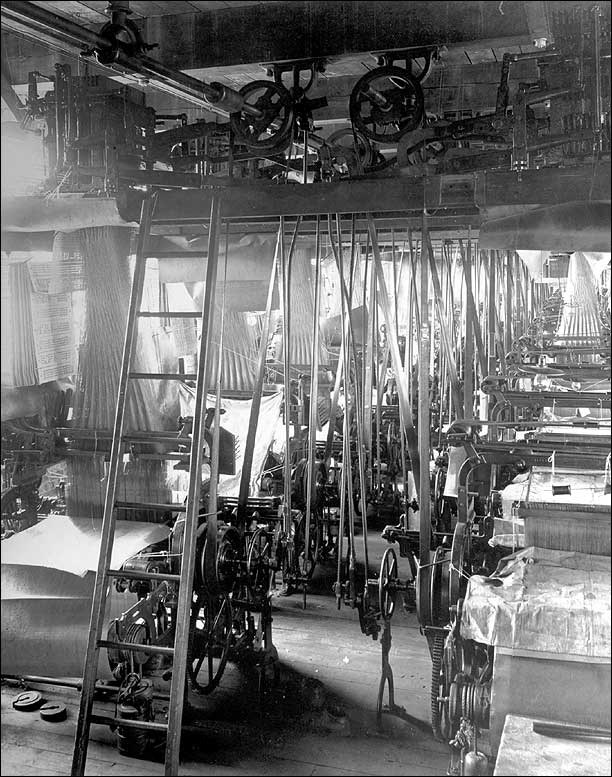

Photo 3: Silk weaving mill in the Great Falls/S.U.M. Historic District.

Photo 4: Jacquard silk looms, ca. 1900.

(Courtesy of the Passaic County Historical Society)

Photo 4 shows rows of Jacquard looms. The large punched cards hanging on the left programmed the looms to produce the elaborate and colorful silk fabrics demanded by the New York fashion industry. Although the looms were usually well spaced and protected in newer mills, government inspectors reported that machinery in the older mills was often packed so closely that it was difficult to move about without being struck by moving parts of the equipment.

Questions for Photos 3 and 4

1. Compare Photo 3 with Photo 1. Why do you think the windows on the weaving mill are so large?

2. According to a 1919 government report, the chief source of fatigue in silk weaving was not the physical work involved but the "tension of continued watching, of being constantly on the alert."¹ What do you think working in a mill like this would have been like? How difficult do you think it would have been to tend four of these looms at a time? How much difference would it have made if the looms stopped automatically when a thread broke?

3. Based on Photos 1 through 4, how do you think working conditions in the dye houses compared with those in the weaving mills? Where would you have preferred to work? Review Reading 1. What do you think the dye house workers and the weavers had in common? How did they differ? What problems do you think they would have had working together to seek improvements in their working conditions?

¹ National Industrial Conference Board, Hours of Work as Related to Output and Health of Workers: Silk Manufacturing (Boston, MA: National Industrial Conference Board, 1919), 14.

Visual Evidence

Photo 5: Belle Vista (Lambert Castle), 1896.

Questions for Photo 5

1. Photo 5 shows Belle Vista in 1896. The house is located on the side of Garret Mountain and is one of Paterson's most visible landmarks. Why do you think most people in Paterson called this house "Lambert Castle"?

2. Why do you think Catholina Lambert would have built such a house in Paterson? What does it reveal about his financial and social status?

3. According to a government survey of the silk industry published in 1911, "the silk manufacturers of to-day were the skilled operatives of yesterday."¹ What do you think someone just setting up his own business in Paterson might have thought when he looked at Lambert's house? What do you think one of the strikers might have thought?

¹ U.S. Senate, Report on Condition of Woman and Child Wage-Earners in the United States, Vol. IV: The Silk Industry (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), 198-99.

Visual Evidence

Photo 6: Strike rally at the Botto House, 1913.

Questions for Photo 6

1. What does this house reveal about Pietro Botto's financial and social status?

2. Review Reading 2. Can you find the features that Elizabeth Gurley Flynn describes in her reminiscences?

3. This photo shows one of the Sunday rallies that were held at the Botto House during the silk strike. Why were these rallies held? Why do you think thousands of striking workers came to them?

4. How do you think a worker who had received no pay for three or four months would have felt coming out to Haledon to hear one of the famous leaders of the IWW, such as Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, "Big Bill" Haywood, or Carlo Tresca?

Putting It All Together

Although the silk industry in Paterson had its own special characteristics, the factors that contributed to its rise and fall can be found in cities and towns all over the United States. The following activities will help students understand how industries and the communities that depend on them change over time.

Activity 1: Working and Workers

Remind students that the issue that triggered the silk strike of 1913 was a change in worker responsibilities. The new looms Harry Doherty installed made it possible for one worker to tend four looms at a time. For the mill owners the new equipment represented progress--expanding production, reducing costs, and benefiting everyone. For the workers, the new looms and the change in responsibilities represented a stretch out--a way to get more work without paying more money. They did not think that they would benefit from any increases in productivity, and they were sure that the changes would inevitably lead to increased unemployment and decreased wages.

Ask students to discuss as a class the introduction of modern machinery and the question of who should benefit from it. Why do they think a question of work assignments, rather than disputes about issues like wages or working conditions, led to the strike? Who do the students think should make decisions about the introduction of new technologies? Do they think the effects on workers and their lives should be taken into account? Do they think the workers should play a role in decision-making? The new machinery represented a substantial capital investment for the owners. How much of the increase in productivity could be considered a return on that investment? Ask them to defend their answers.

Activity 2: Labor Unions and Strikes

The silk strike in Paterson occurred during a period when there were major strikes in many parts of the United States. Divide students into groups and have each group research the story of one major union in America--the Knights of Labor, Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), American Federation of Labor (AFL), Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), and United Mine Workers of America (UMW). American history textbooks will provide some of the needed data; library references will provide more of the story. Who did each union represent? Ask the groups to identify major strikes in which each union was involved, which workers participated in the strike, what the issues were, and how the strike ended. Have each group of students present the information they found to the class. Hold a general class discussion of what the unions accomplished in these strikes and how our lives might be different today if organized labor had not existed.

Local union members or representatives might be willing to speak to the class. If so, have the students prepare a list of questions to ask the speaker about how unions operate today. Ask students to compare the current concerns of unions with the issues important to the silk workers at Paterson.

Activity 3: Local Industry

Working in groups, have students research their community to determine what industries were important in its history. Remind them that industries do not necessarily have to be in factories. Even small towns had flour mills, saw mills, cotton gins, or lime kilns. For the late 19th and early 20th centuries, published directories and telephone books, often available at local public libraries, list and frequently have advertisements for local businesses. Between 1880 and about 1910, many towns published books celebrating their history and giving brief biographies of leading businessmen; these, too, are often available at local libraries or historical societies. Have each group choose a different year and determine what seem to have been the most important industries in their community in that selected year. Then have the groups find comparable data for two or three additional years between the first year and the present. As a class, discuss the findings of each group and try to determine why certain industries disappeared, while others remained successful. Finally, ask groups to find out whether any buildings remain that were associated with early industries. If so, how are they being used today? If industries that were once important in the community have closed, what effect has that had on the community?

Paterson, New Jersey: America's Silk City--

Supplementary Resources

After reading Paterson, New Jersey: America's Silk City, students will know more about the causes and effects of a famous strike and how it affected those who were involved in it. Students and educators who want to know more will find much useful information on the World Wide Web.

Paterson Friends of Great Falls

Visit the Paterson Friends of Great Falls website as it contains a great deal of information on the history of industry in Paterson, the Great Falls/S.U.M. Historic District, and the silk strike. It also includes historic and current photos and links to related sites. The site was created to encourage the preservation of the National Historic Landmark District against unsympathetic development.

Library of Congress: American Memory Collection

Search the American Memory Collection for various primary documents relating to labor history, labor unions, the IWW, and more. Of particular interest is an oral history with the Schagens about working in Paterson.

LABOR ARTS

LABOR ARTS is a virtual museum that gathers, identifies, and displays images of the cultural artifacts of working people and their organizations. Included on this website is called Solidarity Forever: A Look at Wobbly Culture which includes cartoons, graphic art, songs and poetry, evoking the vibrant folk culture of the IWW of the early 20th century.

A Short History of American Labor

The State University of New York at Albany website includes a useful overview of labor history that helps put the Paterson strike in a national context.

Tags

- industrial history

- industry

- workers

- unions

- labor history

- industrial workers of the world

- immigration

- new jersey

- new jersey history

- silk mills

- strike

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- science

- migration and immigration

- early 20th century

- gilded age

- twhplp