Following the American Revolution, hostility grew between native tribes and white settlers on the western frontier. The U.S. government sent officials and soldiers to try and maintain an awkward peace, but aggressive policies threatened native peoples’ autonomy and independence. Native resistance turned into an alliance with the British.

“A breach of faith, is with them an utter abomination, & never forgotten” Lieutenant Colonel George McDonall describing relations with native tribes, May 1815

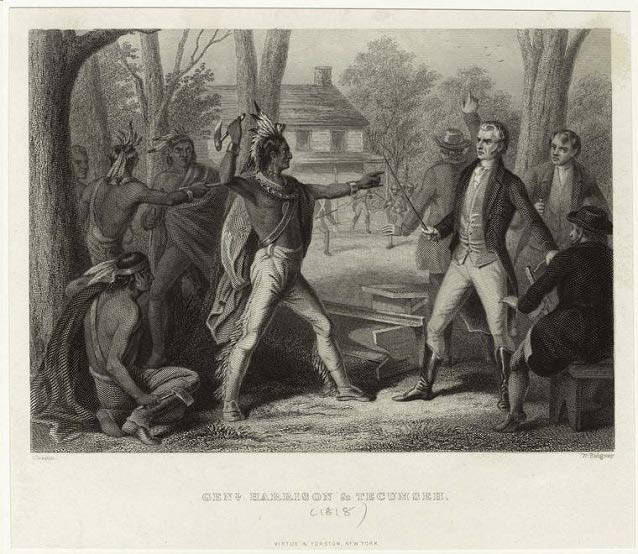

Art and Picture Collection, New York Public Library

To many whites, both Americans and British, the War of 1812 appeared principally as a struggle between a European power and its former colony. But the war looked different to the tens of thousands of Native Americans living in North America, who would play a decisive role in shaping the course of the conflict.

Indigenous peoples throughout North America had been coping with an increasing European presence since the early seventeenth century. But tensions between Native Nations and encroaching white settlers mounted rapidly following the American Revolution. While some tribes managed to secure their position through land deals with the U.S. government, other tribes claimed that the treaties were void. Native mounted ongoing resistance against westward expansion of white settlers from the east.

They found the British a valuable ally in that resistance. Because the British government was more interested in alliance and trade than settlement, they offered weapons and supplies to northwestern tribes, and promised that native land would remain untouched in lands still controlled by the Crown.

Despite near-constant conflict between Americans and natives along the frontier in the early years of the nineteenth century, not all tribes were committed to fighting in a war between Britain and the U.S. As late as June 1812, the Buffalo Gazette reported that local chiefs in New York State had “a general understanding among them to take no part” if hostilities broke out.

On the far western border, however, conflict between the U.S. government and native tribes escalated. Between 1800 and 1811, in the newly created Indiana Territory, Shawnee leader Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa gathered supporters to resist white expansion. In am 1810 speech, they warned Governor William H. Harrison that they would defend their land if the settlers continued to push westward.

In November 1811, Harrison sent an army to wipe out the natives’ headquarters in Prophetstown, near the Tippecanoe River. Although the native warriors inflicted numerous casualties, they finally retreated. The Americans burned the town and the food supply.

The remaining warriors fled north to seek support from the British government. Although many tribes still hoped to negotiate a settlement with the U.S. government, the Battle of Tippecanoe showed that Harrison was no longer willing to negotiate a deal. The constant threat of white expansion and military action by the United States pushed many northwestern tribes into an alliance with the British.

The native warriors who moved north were invaluable to the British, nearly doubling their force. At the Battle of Fort Detroit, Tecumseh and his warriors proved that the British and native alliance would help shape the outcome of the war.

Last updated: August 14, 2017