Hungry Horse Dam, on Montana’s Flathead River, has a name as charming as the timbered high country in which it stands. Just 15 miles from the west entrance of Glacier National Park and 44 miles from the Canadian border, Hungry Horse Dam knows the kind of winters that fur trappers experienced in the region in the early 1800s. When the snow flies in Montana, it can be a dangerous situation for man or beast, including horses. That’s what happened to Jerry and Tex, two freight horses working the Montana oil rush in the winter of 1900-01. They wandered away and weren’t found until a month later, belly-deep in snow and skinny as lodgepole pines. Nursed back to health, Jerry later pulled a fire wagon in Kalispell, and Tex did the same for a mercantile company. And so the name Hungry Horse stuck.

In 1953, Hungry Horse Dam was completed on the South Fork of the Flathead River, in a scenic spot surrounded by more than 25 mountain peaks. The dam took five years to build as construction shut down every winter, and crews labored to clear thousands of trees from the site, a job accomplished by chaining a huge, 4½-ton steel ball to a couple of tractors and pulling it through dead timber and over stumps left by loggers. One contractor built an iron drag shaped like an umbrella to gather the timber into a pile for burning. When Hungry Horse Reservoir inundated a fire lookout tower, the Bureau of Reclamation rebuilt it elsewhere, along with U.S. Forest Service roads, bridges, and buildings.

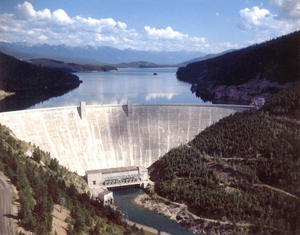

At 564 feet high, Hungry Horse is one of the largest concrete arch dams in the United States, and its morning-glory spillway, with water cascading over the rim and dropping 490 feet, is the highest in the world. Hungry Horse was built not for irrigation, as were so many other Reclamation dams, but to provide water storage that could be used to increase hydroelectric power production at Grand Coulee and Bonneville dams, downstream on the Columbia River. Hungry Horse, its reservoir, and the four generators in its powerplant (which produce about one billion kilowatt hours of power a year) also provide flood control and electricity to the surrounding area, including the towns of Kalispell, Whitefish, and Columbia Falls.

As early as 1921, the U.S. Geological Survey began studies of the Hungry Horse Dam site, but it wasn’t until 1943, with the nation in need of all the power it could find for war production plants, that organized support materialized. The Corps of Engineers initially proposed raising the level of Flathead Lake to store more water for downstream powerplants, but local opposition to damming the pristine lake, the largest freshwater lake in the American West, turned the focus to the nearby South Fork of the Flathead River.

On June 5, 1944, Congress authorized the project and, despite its link to wartime production, pre-construction work did not begin until August 1945, just as World War II was ending. Two outfits were hired to clear more than 20,000 acres of trees from the reservoir site in what the workers dubbed “Operation Highball,” named for the heavy steel balls, eight-feet in diameter, used to clear timber. The General-Shea-Morrison Company of Seattle won the contract to build the dam and powerplant, and set to work in April 1948. The company, as Eric A. Stene writes, erected a construction camp, complete with houses and dormitories for workers, a warehouse, schoolhouse, grocery store, and hospital. To permit nighttime work, General-Shea-Morrison strung floodlights across the steep, narrow canyon where Hungry Horse Dam took shape.

As Boyles Brothers Drilling Company constructed the morning-glory spillway, which acts like a giant drain in the reservoir, work on the dam proceeded simultaneously, with General-Shea-Morrison pouring the first concrete on September 7, 1949. When November arrived, work on the dam shut down for the winter, as it would again in the winter of 1950-51 and again in 1951-52. When spring came round, work resumed until the final block was finished on October 4, 1952. Three days earlier, President Harry S. Truman threw the switch to begin operating the Hungry Horse Powerplant, then attended a dedication ceremony at Flathead County High School in Kalispell.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017