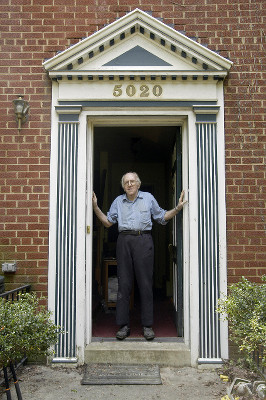

Photo by and courtesy of Patsy Lynch, 2007.

Start here. We exist.

We, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer people (LGBTQ), all the subdivisions of the sexual and gender minority community, exist in America. The places we remember and hold dear, those places that have become part of our identity, also exist. Still. Many of them.

In the 1960s no lesbian, gay man, bisexual, transgender person, or queer gave a thought to their sites and actions being historic. They were struggling for their basic rights, explicitly denied them by their government and the larger society around them. As Dr. Franklin E. Kameny, often called the “father” of LGBTQ civil rights, asserted with some asperity in his 1960 petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court “Probably [homosexuals] most dominant characteristic is their utter heterogeneity. Despite [the] common popular stereotype of a homosexual which would have him discernible at once by appearance, mannerisms and other characteristics, these people run the gamut of physical type, of intellectual ability and inclination and of emotional make-up … ”[1].

In making his case for tolerance and an end to restrictions on homosexuals’ rights, Kameny was in this instance most focused on discrimination in employment, though in addressing his own particular case, he noted that those rights were the equal of every American’s rights and should not be legally, logically, constitutionally, or on any other basis diminished. The depth of Kameny’s asperity was plumbed in his outraged summary of the government’s case for oppressing homosexuals’ employment in a resonant indictment of federal oppression:

“Respondents’ [US Civil Service Commission, Army Mapping Service, the US Army] case is rotten to the core. Respondents’ case had been shown to fail factually and to be defective procedurally; the regulations upon which they base their case have been shown to be legally faulty, invalid, and unconstitutional; their policies have been shown to be improperly discriminatory, irrational and unreasonable, inconsistent and against the general welfare, and unconstitutional. …

The government’s regulations, policies, practices and procedures, as applied in the instant case to petitioner specifically, and as applied to homosexuals generally, are a stench in the nostrils of decent people, an offense against morality, an abandonment of reason, an affront to human dignity, an improper restraint upon proper freedom and liberty, a disgrace to any civilized society, and a violation of all that this nation stands for. These policies, practices, procedures, and regulation have gone too long unquestioned, and too long unexamined by the courts.”[2] Read more » [PDF 2.0 MB]

[1] Franklin Edward Kameny v. Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army et al., Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, no. 676, US Supreme Court, 1960, 36. Kameny’s writ was intended to win him a Supreme Court review of his appeal against dismissal from the Army Mapping Service on grounds of homosexuality in 1957. It did not. However, in articulating his arguments against US government repression of homosexuals and its ban on employment of homosexuals, Kameny set forth clearly many of the arguments and goals that would characterize his activism over the next fifty-one years. The Dr. Franklin E. Kameny Residence is located in the northwestern quadrant of Washington, DC. It was listed on the NRHP on November 2, 2011.

The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Part of a series of articles titled LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History.

Last updated: October 10, 2016