Lincoln's primary goal as President was to save the Union. He viewed the secession of states as unconstitutional and a terrible end to the experiment of American democracy. Critical to his war strategy and his success as President was preventing more states from seceding.

"The value and utility of slavery in Maryland has already been destroyed by the war; the domestic institution can receive no further detriment here." October 1, 1862 The Frederick Examiner

The "Border State" Tug of War

Lirbray of Congress

Keeping the so-called "Border States" in Union control was of paramount importance. Maryland was one of these states, a slave state still in the Union. There were many southern sympathizers in the state, but the majority were loyal Unionists. Still, any hint of rebellion was quickly addressed by Lincoln's administration and the military. The issue of emancipation could ignite dangerous reactions from the people of Maryland. Lincoln proceeded cautiously and stayed informed about what Marylanders were thinking.

The people of Frederick remained divided in their loyalties before and after the Maryland Campaign. On December 28th, Maj. Peter Vredenburgh, of the 14th New Jersey stationed at Monocacy Junction, reflected local sentiment and reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation, when he wrote, "it will ruin us. Men here who were good Union sympathizers before are now on the other side."

The Frederick Examiner noted on October 1st that Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation would have no effect on Maryland as it did not apply to enslaved people in the state. However, it asserted that even if the proclamation were to apply, "the value and utility of slavery in Maryland has already been destroyed by the war; the domestic institution can receive no further detriment here." The editors proposed emancipation with some form of compensation for the loyal Maryland slave-owners. By the summer of 1862 slave advertisements in the Examiner had practically disappeared; replaced with advertisements such as the following: "Wanted to Hire, a middle age slave woman from the country, by the month or year, to cook, wash and iron for a small family. A comfortable home and good wages."

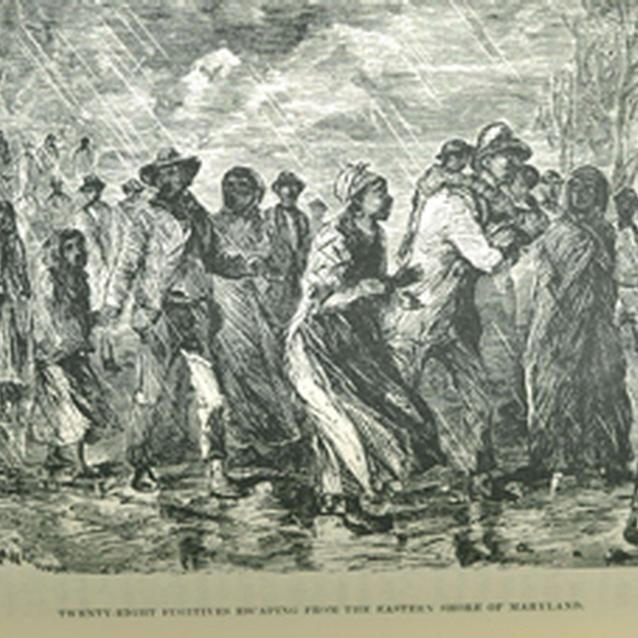

African Americans in Maryland, slave and free, were caught in the middle. Earning freedom by escaping slavery or avoiding Confederate patrols was important, but keeping freedom with Union victory and abolition was the real prize.

The Shadow of John Brown

Library of Congress

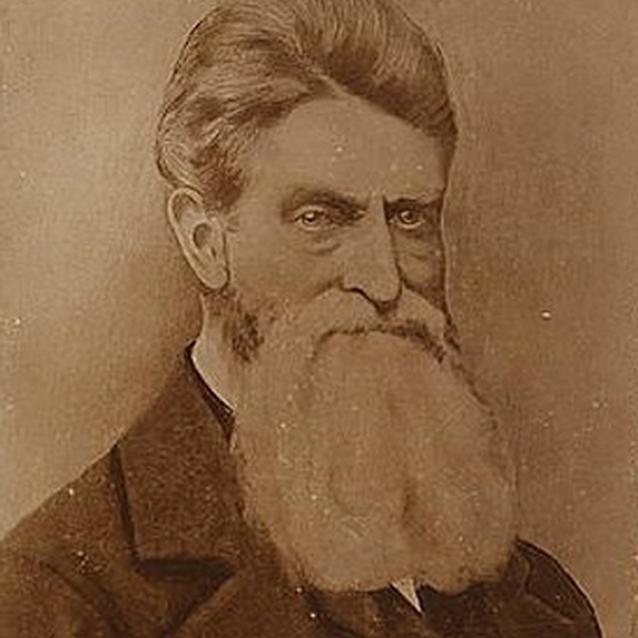

Just yards from the fire engine house where John Brown, a zealous abolitionist, made his final stand against slavery in 1859, a Union officer took his own stand defending a group of African American men.

Between September 13th and 15th, 1862, as part of Lee's Maryland Campaign, Confederate troops under Gen. "Stonewall" Jackson surrounded and captured the 12,500 man Union garrison at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. In addition to the captured artillery, wagons, mules, small arms, and thousands of pounds of food, Confederates were rounding up hundreds of Contrabands or runaway slaves who had sought refuge behind Union lines. Col. William Trimble of the 60th Ohio Volunteer Infantry was concerned. He had a number of free African Americans who had been working as servants and teamsters for his regiment since they enlisted in Ohio. These men were free and Trimble was determined they would stay free. Trimble received passes for his free workers from Confederate Gen. A.P. Hill, allowing them to stay with the regiment.

On the morning of September 16th, the 60th Ohio, now paroled prisoners, prepared to march across the Potomac River pontoon bridge into Maryland. The regiment was halted by a Confederate guard with crossed bayonets. The Confederate officer in charge refused to accept the passes for the freedmen and the rebels began "dragging the colored boys from their positions near the officers." Trimble reached into his holster and drew his revolver. "My men are unarmed--I am not!" he shouted. "I'll sell my life for these free boys. Unhand them! Guards, give way! Regiment, march!" The Confederates stepped aside, and the African Americans marched across the pontoon with the 60th Ohio.

A proclamation of emancipation would not be issued for another six days, but for Col. Trimble and the men of the 60th Ohio, the war was already about freedom.

Part of a series of articles titled Born of Earnest Struggle.

Previous: It Has To Start Somewhere

Next: A Chance at Freedom

Tags

Last updated: February 3, 2015