The most effective beaver dam that has come to my attention was built at the outlet of Wonder Lake in 1960; it raised the water level ... over 2 feet, [holding back] well over 100 million cubic feet ... of water. Adolph Murie, in "The Mammals of Denali"

NPS Photo / Kent Miller

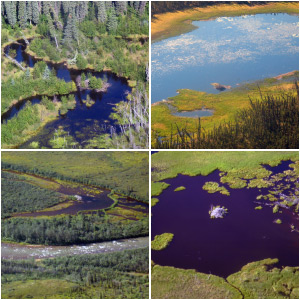

Visitors to Denali National Park and Preserve can easily observe beavers (Castor canadensis), or at least the results of their activities (dams and lodges)—also known as beaver works—at Horseshoe Lake, in the small tundra streams and ponds between Eielson Visitor Center and Wonder Lake, at Wonder Lake and its inflowing creek, and along Moose Creek.

During the early 1800s, beavers were trapped and hunted to local extinction in many part of the U.S. and Canada, mainly because of the popularity of beaver felt hats in Europe. Contemporary beaver populations are still very low, numbering 6 to 12 million individuals, compared to population estimates of 60 to 400 million beavers prior to European settlement.

Patterns of beaver harvest in Alaska lagged those in the lower 48 by several decades, but beavers also became locally extinct in some Alaska areas in the early 1900s. Beaver trapping was banned for nearly a decade starting in 1910, but continues legally today in many parts of Alaska, including the preserve portions of Denali.

Beavers Modify the Hydrologic Landscape

Known for their busy-ness, these large rodents change their environment by building dams and cutting trees. In doing so, they modify the hydrology (water movement and distribution) of nearby ecosystems. But beavers don’t stay active in one place forever. As beavers modify one area and then die out or move on as they deplete food supplies, they create a shifting mosaic of active wetlands, abandoned beaver-dam wetlands, and interspersed uplands. Such mosaics can be thought of as hydrologic landscapes, a term coined by a USGS hydrologist (Tom Winter) to help conceptualize how parts of the water cycle like ground-water, surface-water (lakes and streams), and atmospheric water interact with the land.

NPS Photo / Kent Miller

Studying Beaver Habitats in Denali

How do shifts in beaver occupation affect Denali’s hydrologic landscape? Addressing this question in Denali provides an opportunity to study beaver populations and their habitat use in a setting similar to what existed in boreal North America prior to European settlement. In many areas of the park, beaver populations likely have been relatively undisturbed by humans for decades. The fact that beaver populations are generally uninfluenced by human activities in the park portion of Denali presents an interesting opportunity to study how beavers have influenced or are infl uencing water storage patterns and water movement through the landscape. Such studies may help develop models of past hydrologic landscapes, and of future ones as beaver populations continue to rebound.

As a starting point to understanding beaver populations in Denali, scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey, Alaska Science Center initiated a two-part study in 2007: (1) a ground-based survey to learn how to recognize active versus inactive beaver works, and (2) an aerial survey, along a fl ightline through habitats suitable for beavers, to map locations of active and abandoned beaver works in Denali’s hydrologic landscape.

USGS photo

Active and Abandoned Beaver Works

Because beaver use of a habitat is temporary, researchers wanted to know what percentage of beaver works are currently inhabited by beaver families. They spent several days working at a large beaver complex on Lake Creek near the Wonder Lake Ranger Station with both active and abandoned dams and lodges, including one abandoned in 2005, as dated by park rangers.

Researchers conducted a topographic survey of this area to develop a detailed map and locate even very old beaver works covered by dense vegetation. They were able to later compare this map to the aerial photograph of the same location taken a few days later. This comparison was designed to help them interpret other beaver works they observed along the flightline—to determine the relative number that was active versus abandoned.

USGS photo

Aerial survey of Denali’s hydrologic landscape

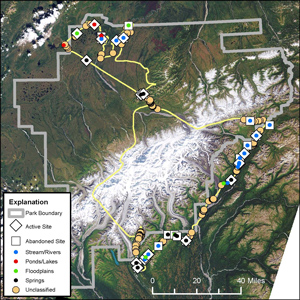

On August 10, 2007, with the help of pilot Jim Webster flying a Cessna 185 float plane, researchers conducted an aerial survey to locate beaver works. The flight took off from Summit Lake south of Cantwell, crossed the Alaska Range northeast of Denali, proceded over the Muldrow Glacier and Wonder Lake, continued to Lakes Minchumina and Chilchukabena, and returned to Summit Lake flying south around the Alaska Range.

Because it was sunny, researchers sitting on both sides of the plane, with GPS and cameras in hand, had clear views of many beaver works along this flight path. Based on the low-altitude flight and good visibility, researchers estimated that they could adequately spot beaver works within 0.6 miles (1 km) of the plane, and thus surveyed approximately 6 percent of the park’s land area.

If the flight route had been chosen randomly or along a systematic grid, researchers could have estimated the total population of beaver works in Denali. However, this estimate cannot be made because researchers purposely surveyed particular habitats within the park where beavers were hypothesized to occur.

Results of flightline survey

After reviewing each surveyor’s photograph, which was time-linked to GPS points, researchers determined that 239 individual beaver works were observed along this 440-mile (708-km) flightline in the park.

The most interesting initial finding was that a few areas in the park had very high beaver work densities (particularly along the mountain front south of the Alaska Range, around Wonder Lake and Moose Creek in the Kantishna Hills, and between Lakes Minchumina and Chilchukabena), while other areas that appeared to be similar to the beaver-rich ones had no active or abandoned beaver works. It should be noted here that some beavers use bank dens (rather than lodges) that would be very hard to locate from a plane.

From the previous ground reconnaissance to distinguish active and inactive beaver works, researchers classifi ed the aerial sightings as 47 percent sites active and 53 percent sites abandoned. However the comparison at Wonder Lake of the aerial and ground surveys suggested that dams were underestimated from the air by about 60 percent and lodges by about 30 percent. Thus, the number of beaver works viewed from a plane, particularly abandoned sites, was likely underestimated.

Management Implications

This preliminary study gathered data about how beavers are distributed among the habitats in Denali’s hydrologic landscape. The study helps confirm for Denali, as scientists have described in greater detail for other places, e.g., boreal forests, that the influence of beavers and their modification of the hydrologic landscape are significant and can persist long after the beavers are gone.

Part of a series of articles titled Denali Fact Sheets: Biology.

Last updated: June 7, 2016