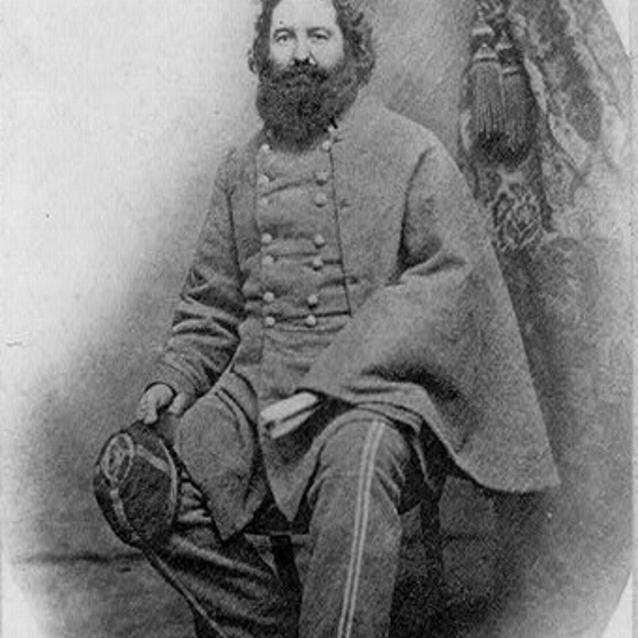

Special Orders 191 called for a three sided attack on the Federal garrison at Harpers Ferry. Gen. Walker commanding one wing of Jackson's three-pronged advance, crossed the Potomac and advanced across the northern Virginia countryside to the eastern slope of Loudoun Heights. Col. Dixon Miles, commander of the Federal garrison, had neglected to post any men or artillery on these heights, considering them to be well within the range of Federal gunners on nearby Maryland Heights. Walker, facing no Union opposition, moved a battery of artillery up onto Loudoun Heights and, on September 14th, exchanged the first artillery fire with Union guns at Harpers Ferry.

Divide and Conquer

Library of Congress

Gen. McLaws commanded the second wing of the Confederate advance. McLaws understood the topography around Harpers Ferry well. Maryland Heights was the highest ridge overlooking Harpers Ferry. On September 13th, the Confederates drove 4,600 Union defenders off the mountain despite "a most obstinate and determined resistance." One day later, McLaws opened fire on Harpers Ferry with four guns.

Jackson commanded the third Confederate wing. Advancing from Frederick, he swept across western Maryland, crossed the Potomac at Williamsport, captured Martinsburg, and came up behind Harpers Ferry - marching over 50 miles in less than two days. Jackson's 14,000 man column occupied School House Ridge, sealing the trap on the surrounded Federal garrison and winning a great victory.

Jackson did not have long to rest on his laurels, though. Lee had expected the mission to be completed on the 12th, and by the 15th, word came of dangerous movements by McClellan. He needed Jackson back with him as soon as possible. Leaving Gen. A. P. Hill to parole the Federals and make arrangements for the spoils they took, Jackson was on the march again. This time, he was headed for a rendezvous with Lee around the town of Sharpsburg, on the banks of the Antietam creek.

When did Lee know the orders were lost?

Library of Congress

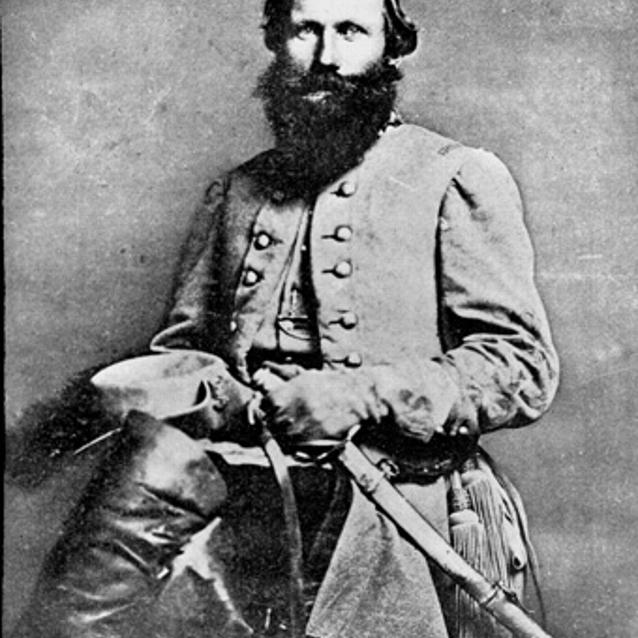

When exactly Lee knew McClellan had a copy of his orders is also a difficult issue. A popular story circulated that when McClellan received the orders he was meeting with a delegation of men from Frederick. Among these men was a sympathizer who told Confederate Major General Jeb Stuart that McClellan had the orders. Perhaps a civilian was present who saw that there was excitement and movement in the Union camp; however, there is no conclusive evidence that Confederate's were alerted to the fact that the Union had the orders.

Lee contributed to some of the misinformation on this matter. In an 1868 letter to D.H. Hill, Lee said he knew on September 14 that McClellan had the orders directing the movement of his army, but it is clear from Lee's wartime correspondence that he did not know a copy of Orders 191 was in Union hands. In a September 16, 1862 letter to Davis, Lee gave no indication that he knew about the lost orders. There was also no mention in any wartime reports of Longstreet, D.H. Hill, or Stuart. Lee's aid-de-camp, Colonel Charles Marshall noted in 1867, in a letter to Hill, "I remember perfectly that until we saw that report (by McClellan) General Lee frequently expressed his inability to understand the sudden change in McClellan's tactics which took place after we left Frederick." The New York Herald did report on September 14 that Union officers had Lee's orders, and the same was reported in a Washington newspaper on the 15th, but it seems that Lee did not know about it until either January 1863 from an article in Journal of Commerce, a weekly magazine out of New York, or in March 1863 when McClellan testified about the finding of the orders before the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of War.

Part of a series of articles titled The Lost Orders.

Previous: The Special Orders are Written

Next: The Mystery

Tags

Last updated: February 4, 2015