Americans remember the War of 1812 as a second war of independence, as a war to force the British to give up practices that violated American rights and undermined US sovereignty. But this war was a byproduct of a much larger conflict in Europe.

The only way France and England could wage war was by targeting one another’s trade. As the leading neutral with a large and far-flung overseas commerce, the United States got caught in the middle of this trade war.

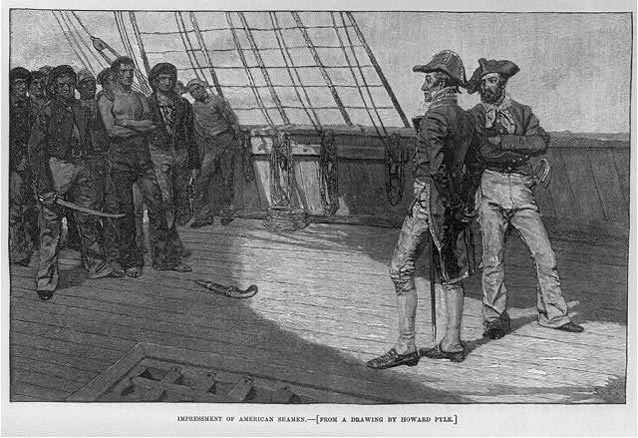

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

In what is sometimes called the Second Hundred Years War (1689–1815), Great Britain and France fought off and on for more than a century to determine which nation would dominate Europe and the wider world. In the final round of this contest—the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815)—Great Britain adopted maritime practices that caused the War of 1812. Far from being isolated from events in Europe, the War of 1812 was a direct outgrowth of the Napoleonic Wars.

After Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson’s great victory over the French and Spanish fleets off the coast of Portugal in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), Great Britain was undisputed “Mistress of the Seas.” But because Napoleon won an equally decisive battle six weeks later at Austerlitz (in the modern Czech Republic), France was now master of the Continent. With each belligerent supreme in its element, the only way they could wage war was by targeting one another’s trade. As the leading neutral with a large and far-flung overseas commerce, the United States got caught in the middle of this trade war.

Because Great Britain controlled the seas, her encroachments on American rights were considered more serious. The two leading causes of the War of 1812 were the Orders-in-Council, which sharply curtailed American trade with the European Continent, and impressment, which was the British practice of conscripting seamen from American merchant vessels. Although the Royal Navy sought to confine impressment to British subjects, many Americans—probably around 6,000 between 1803 and 1812—were caught in the dragnet. These maritime policies had a direct and significant impact on the United States, but their primary purpose was to further Britain’s war effort against Napoleonic France.

Part of a series of articles titled The Global Context of the War of 1812 .

Last updated: March 6, 2015