Last updated: August 8, 2025

Article

Women, Empire, and Commemoration in the North American West and Pacific

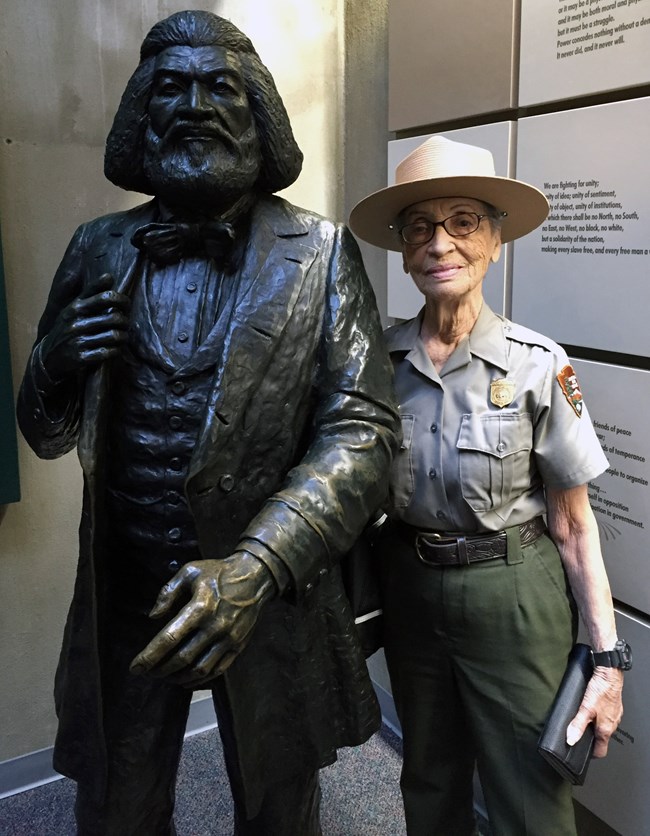

Photo courtesy of Betty Reid Soskin

Article written by Ellen Hartigan-O'Connor, Lisa G. Materson, Charlotte Hansen Terry

Reflecting on her own experiences as a civilian working for the US Air Force during World War II, Betty Reid Soskin wrote in her memoir, “I have such a love-hate relationship with Rosie!”1 In the California Bay Area, activist Betty Reid Soskin brought the stories of racial discrimination and segregation into the interpretation at the Rosie the Riveter WWII Home Front, a National Historical Park site that commemorates the work of women who took up industrial labor for the war production effort.2 The famous image of a white working woman—a Rosie—flexing her bicep circulates on magnets and potholders sold at the park and elsewhere, reinforcing a partial truth. Soskin’s interpretive work insists on commemorating the full truth, of expanded work opportunities contrasted with enduring racial hierarchy, both born of the region’s imperial legacies.

Commemoration always includes a struggle over whose interpretations and politics will prevail.3 Vigorous debate accompanied the 2020 centennial celebration of the Nineteenth Amendment, which created a vast electorate of new voters and removed sex as a bar to voting, but left in place barriers set by race, class, and colonial status. Just four years after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the United States passed the Immigration Act of 1924 that deemed Asian people “aliens ineligible for citizenship,” indicating ways that race and imperialism underlay “women’s suffrage.”4 The double edge of the amendment was sharpened by the legacy of US colonialism on the North American continent and overseas with implications for Soskin, “Rosies,” and the Asian-American women forcibly removed from the California Bay Area during World War II.5

National Parks, first created in the US West and later expanded further into the Pacific World, were part of the double edge of US empire, and they offer valuable contemporary sites from which to recover women’s lives in the past by looking at the women who created them, worked in them, and lived in and around them. In fact, diverse women have used park sites for their own political and historical purposes. Indigenous women have used parks that historically erased the history of their ancestors’ dispossession to call attention to it and to showcase their nations’ cultures. White women, deploying their own political power, led numerous efforts to preserve “from injury or spoliation” these same landscapes that were functioning homelands to Indigenous women and their families.6 To place women’s lives in time and physical space in the contemporary US West and Pacific expands interpretation of public monuments and memories to encompass a deep history of conquest, empire-building, and unequal citizenship that National Parks themselves facilitated and have often erased. In women’s family connections, working lives, and activism for rights and representation, we understand the richness of a story just beginning to be commemorated.

NPS Photo

Colonial Intimacies and Kinship

Nineteenth-century histories of American men who moved West often reported that they “died single” when in fact they had Mexican or Native wives and large extended families.7 This dominant narrative is still reflected in many National Parks, which commemorate white men’s lives as solo adventurers, while erasing the multi-racial, multi-cultural families that typified the area. Such stories also conceal the basis of white men’s political and economic power in the region, which rested on these same family connections. In fact, women played key roles in the “intimacies” of US conquest.8

Intimacies shaped economic mobility in the West and the Pacific. Kinship networks were the basis of the global fur trade from the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Strategic marriages between each wave of colonizers and the families already occupying the land were essential to the political and economic goals of first the Spanish and then the United States. Kinship histories are therefore essential to understanding a place such as the Point Loma Lighthouse in San Diego. In 1775, Juan Bautista de Anza recruited Mexican families to create a Spanish stronghold in what is now California on a journey that included widow María Feliciana Arballo. She settled and married in San Diego, and her children rose to prominence in Spanish colonial society.9 A century later, María Arcadia Alipás, born to a prominent Californio family, married Robert Israel, an Anglo veteran of the US-Mexican War who moved into the territory surrendered by Mexico to the United States. In the new US state of California, Israel was absorbed into the Alipás family, who helped establish the couple as ranchers and later as partners in keeping the Point Loma Lighthouse guiding trading ships into San Diego Bay.

Forced intimacies, through capture and sexual violence, put women into key roles as intermediaries.10 As a Nez Perce teenager, Wetxuwiis was kidnapped by Blackfeet or Atsinas in Montana and traded across North America as a captive and a wife before being sold to a white man in the Great Lakes region. When she escaped home to the Nez Perce, she carried with her a baby son born of her captivity. Some years later, in 1805, she convinced Chief Twisted Hair to aid the wandering, starving Lewis and Clark party when her people encountered them in camp, sharing critical information about the Columbia River and Pacific coast with them. The Corps of Discovery, as the US Army unit was called, depended on the Indigenous knowledge brokered by women such as Wetxuwiis and Sacajawea, the Lemhi Shoshone woman who accompanied them, also carrying a baby.

Indigenous intimacies shaped the warfare that was part of dispossession and forced removal at the hands of the US military, as Indigenous women and children traveled with warriors as a community, established camps, delivered food and horses to the battlefield, and nursed the wounded. During the Nez Perce War of 1877, Indigenous women and men suffered violent conflict together. Western military forts, established as part of US conquest, were places where Native and non-Native women worked as laundresses, nurses (see the Mary C. Lange biography), cooks, and sex workers serving US military men. When these forts became part of the National Park Service, they commemorated brutal warfare that should be understood both as symbols of Indian genocide and sites of Indigenous women’s persistence.

The Work of Empire

As the United States expanded its empire westward in the nineteenth century, women’s labor was essential to laying claim to territory. Anglo-American women established households by giving birth to and raising new generations of settlers supported by inheritance laws that converted hillsides into real estate.11 In many families, a gendered division of labor determined who would move to the West, or who would leave the West in search of work, and who remained behind to care for families and local communities.

Protestant missionary work in the West and Pacific depended on husband-and-wife pairs who embodied the working roles suitable to each gender, such as Marcus and Narcissa Whitman’s Anglo-led missionary efforts in Oregon Territory to convert the Cayuse to Christianity. The Whitmans, in turn, relied on Native Hawaiian working couples including Maria and Joseph Maki.12 Maria Maki and her husband Joseph were members of the Kawaiaha‘o Church in Honolulu, and through it became affiliated with the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). The Honolulu church assisted the Oregon Mission of the ABCFM, sending Native Hawaiian laborers to work on farms in the United States. While the white Whitmans praised the Hawaiian couple as “very useful to us & their good example among the [Cayuse] Indians,” Maria Maki was more than a “useful” wifely example of Indigenous Christianity.13 Native Hawaiians of her generation found in Christianity a way to explore the world, construct a global geography, and even contest colonialism.14 Connections between the Pacific Islands and the US mainland Pacific coast increased in the twentieth century, leading to continued migrations and tensions between various peoples in this region.

NPS Photo, Whiskeytown National Recreation Area

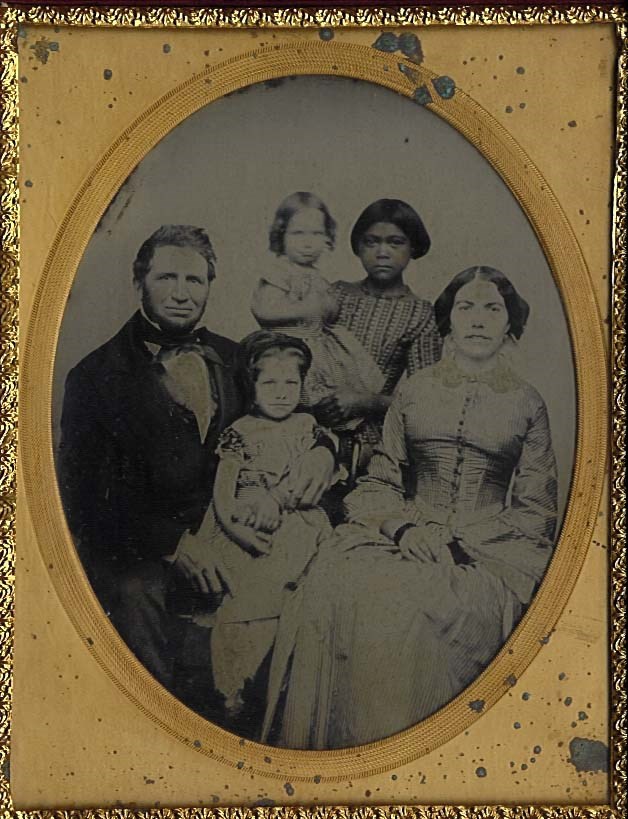

The discovery of gold in California in 1848 brought initial waves of male treasure-seekers, including those from Chile, Mexico, and China.15 Some women found opportunity in the absence of those men’s family members to do “women’s work,” such as the women who operated taverns and boarding houses in boomtowns like Cerro Gordo, in Death Valley (see Petra "Maggie Moore" Romero biography).16 But the mining-focused migration that these women supported with their washing, cooking, entertaining, and sex work also brought waves of violence against Indigenous people, pushing Native girls into servitude performing female labor. California’s 1850 Act for the Government and Protection of Indians legitimized taking Indigenous children from their parents to indenture them to white families.17 One such child, a young Wintu girl known as Kate Camden cared for the children of the Camden family and worked as a servant for others in Whiskeytown, California.18 A picture taken of the Camden family around the time of the Civil War depicts the white couple and their children, one in the arms of their Native servant, an image reminiscent of the family portraits common in slaveholding southern families at the time who sought to create a lasting record of their domestic success and intimate racial dominance.19

In the twentieth century, new labor opportunities and demands reshaped the gendered labor dynamics of the American West. Farmworkers in the region were overwhelmingly immigrants, making Mexican migrants and Asian migrants from China, Japan, and the Philippines a central part of the agricultural landscape of California.20 Faced with labor shortages during World War II, the US created a labor migration program that deliberately split families across its southern border with Mexico. The Bracero Program, which admitted Mexican men only, required them to return to their families in Mexico once their contract ended.21 Family formation, as centuries of empire-making had shown, meant racial and cultural transformations in the United States; in fact, western agriculture as it developed had depended on the labor of migrant families, Indigenous as well as those from Mexico and Asia. The bracero program was designed to stop family formation north of the US-Mexico border with these contract workers.22

Hawaii State Archives, General Photographic Collection, PP-98-13-019, Liliuokalani, Queen of Hawaii, 1838-1917

Rights and Power Structures

US conquest of Indigenous populations during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries disrupted high-ranking Indigenous women’s governing influence and leadership roles, a devastating blow apparent at the highest levels in Hawai‘i. Indigenous Hawaiian women ruled as queens and chiefs within the Kingdom of Hawai‘i’s rank-based governing system.23 Ka‘ōana‘eha and Queen Lili‘uokalani used their power within the royal family to oppose distinct European and American pressures decades apart. Yet both lost their formal governing influence because of their resistance. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Ka‘ōana‘eha’s royal family—internally split over political and religious upheavals of British imperialism—marginalized her because she opposed the Christian missionization that followed Liloliho’s (King Kamehameha II) 1819 abolishment of kapu, a religious and political system of rules governing everyday life (see article on Queen Ka‘ahumanu).24 At the end of the century, US businessmen with American federal government support deposed Queen Lili‘uokalani in order to undermine Native Hawaiians’ massive resistance to US annexation, which the United States ultimately achieved in 1898.25

White women contributed to the imperial forces that upended the governing power of women like Ka‘ōana‘eha and Queen Lili‘uokalani. They did so as missionaries, settlers, and reformers who invoked racial ideologies at the core of US expansionism to advance their goals. White reformers and suffragists, for instance, made gendered arguments about their supposed moral and domestic superiority in carrying out US “civilizing missions” among Indigenous populations in the West and Pacific. They then pointed to their missionizing work to demand formal governing power alongside white men.26 Far from exceptional, such suffrage strategies mirrored those of white Australian, New Zealander, and British women reformers’ embrace of settler and extractive colonialism to advance their own political rights and government involvement.27

White suffrage leaders such as Susan B. Anthony approached national debates over governing new island possessions as opportunities to advance their cause in Congress. Such federal level moments had dwindled by the 1870s after Congress excluded women’s votes from Reconstruction Era amendments. US territorial expansion opened those federal moments up again. In 1898, for instance, Anthony unsuccessfully urged Congress to include women’s political rights in the territorial constitution that legislators prepared for the newly annexed Hawaiian Islands.28 In 1902, she mobilized white women’s civilizing rhetoric before the Congressional Senate Select Committee on Woman Suffrage in her assertion that colonized men should not win political rights before white women in the United States. As Anthony told Senators:

“I think we are of as much importance as are the Filipinos, Porto Ricans, Hawaiians, Cubans, and all of the different sorts of men that you have before you…When you get those men, you have an ignorant and unlettered people, who know nothing about our institutions.”29

Such race-based arguments for the vote further reinforced exclusion of women of color from the national suffrage organization that Anthony previously headed.30

In 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment made it unconstitutional to deny voting on the basis of sex, but millions of women in the North American West and Pacific remained disfranchised alongside the men of their communities because of obstacles to their obtaining full citizenship. These obstacles were rooted in racial discrimination and colonial subjecthood. When the federal government finally conferred birthright citizenship to all Native Americans four years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, for example, approximately one-third of Indigenous women and men were still not US citizens.31 Until 1943, the Chinese Exclusion Act severely limited Chinese immigration and denied those women and men who were permitted entry the right to naturalize as citizens. 32

Courtesy of Japanese American Museum of Oregon.

Citizenship alone, moreover, failed to guarantee the voting rights of women and men who belonged to racial and ethnic minorities. US citizens of Indigenous, Mexican, and Asian descent have also had to mobilize to exercise their right to vote in the face of race and language-based disfranchising measures. Under these circumstances, the suspension of literacy requirements and the extension of provisions for bilingual election material through the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) and its subsequent amendments in the 1970s constituted more of a political rights watershed than the Nineteenth Amendment for many Mexican American, Native American, and Asian American women.33

Likewise, while the US nationals of American Samoa and the US citizens of Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands could access the ballot, it was only for local elections. Territorials were ineligible to vote for the US president, and they did not have a voting representative in Congress. That is still the case. Along with Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands in the Caribbean, the women and men of these United States’ territories in the Pacific remain colonial subjects politically and economically despite their US national or full US citizenship status.

The legacy of racial and colonial exclusion undermined the rights of US women citizens and their communities in multiple other ways beyond the ballot box. The US government’s incarceration of more than 100,000 US citizens of Japanese descent was one of the starkest of examples of the enduring racialization of US citizens as foreign and unassimilable.34 Hana Shimozumi Iki and Kimi Tambara were two of the thousands of Japanese American women who though full US citizens were treated as what historian Mai Ngai characterizes as “alien citizens.”35 Tambara spent the war years at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Oregon, where she edited the camp newspaper. Iki, a celebrated soprano, was incarcerated with her family at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, the largest of the ten US sites of confinement that held Japanese Americans primarily from western Washington, Oregon, and northern California.36

NPS Photo/Jason Hagin

Anticolonial Grassroots Activism

Voting rights was only one dimension of women’s activism in the US West and the Pacific. During the 1960s and 1970s, for instance, collective organizing among women of color focused on sovereignty movements and cultural revitalization.37 LaNada War Jack helped organize the nineteen-month Native American occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969, an important turning point in Native American self-determination that led to further actions to reclaim land and argue for Indigenous sovereignty. Advocating for Indigenous rights connected the environment to human rights, she wrote, “We want the government to pass laws to respect our Mother Earth, with real enforcement to protect the land, the water, the environment, and the people.”38

A new generation of women of color activists also engaged in multiracial solidarities to advance antiracist and anticolonial agendas. Alongside men in their communities, women of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Filipino descent forged pan-Asian and Third World identities in organizations such as the Asian American Political Alliance (AAPA). While a graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley, Emma Gee was a cofounder of this first organization to employ “Asian American” identity in its name and organizing. Penny Nakatsu was one of several women who founded the AAPA chapter at San Francisco State College that was part of the Third World Liberation Front. The TWLF brought in coalition Asian American, Latin American, Native American, and Black students to develop a shared consciousness as “Third World Students, as Third World people, as so-called minorities.”39

Photo by Jay Godwin, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library

Female migrants of color to the West and Pacific took up new forms of activism. The Great Migration in the first half of the twentieth century drew millions of African American families from the South to the West and other regions for job opportunities. Facing racism and discrimination in their new homes, Black women organized their communities to expand access to better jobs, fought red-lining and housing discrimination, and advocated for reproductive rights, better health care, and schooling for their children. Mexican American women helped to organize the 1970 Chicano Moratorium March Against the War in Vietnam, which drew 30,000 protestors to Los Angeles. Activists developed the idea of an “internal colony” of subordinated Black and Brown people within the United States, proposing opportunities for solidarity.40

Female agricultural laborers of California, drawn in search of work from migratory streams of diverse origins, mobilized with shared aims. Dolores Huerta, born in New Mexico and raised in California, became a champion of agricultural laborers and co-founded the United Farm Workers (UFW) union, which drew attention to the exploitative working conditions in California fields. Her organizing brought together migrant Mexicans, Filipinos, and their families in a broader vision of civil rights and social justice, knitting together subjects of US colonialism for workers’ rights.41

NPS Photo/Nez Perce NHP (NEPE-HI-0165)

Conclusion

Projects designed for the public commemoration of women in the past have frequently added women to existing historical narratives that tell a story of progress, such as the abolition movement in the nineteenth century or American military mobilization in the twentieth century.42 Recognizing new locations where women’s lives shaped the present and devising new ways to see the presence of women in existing sites will continue to be the shared project of researchers, educators, and organizers.43

Indigenous women have used their connections to National Park sites in the West and Pacific to reclaim community remains and artifacts and to reject historical erasure. In the mid-twentieth century, Ida Blackeagle, a Nimíipuu woman on the Nez Perce reservation in Idaho, became one of the first cultural demonstrators for the National Park Service, extending a practice of craftwork and cultural demonstration existing in places such as the Hubble Trading Post on the Navajo Reservation.44 In this role, she wove, completed beadwork projects, and constructed cornhusk baskets while visitors watched. Her art expressed enduring Nimíipuu identity and created pieces that visually linked the physical site of the reservation to a deep history of women’s craftwork in her community. Across the Pacific, Geraldine Kenui Bell, the first Native Hawaiian woman to be superintendent of a national park, worked with community members to secure repatriation of the iwi kupuna (sacred ancestral bones) in the Pu‘uhonua O Hōnaunau’s museum accessions records. Restoration connects Hawaiian past, present, and future.

Like Betty Reid Soskin’s interpretive work, Blackeagle and Bell’s approaches to the parks offer roadmaps for combatting intersecting erasures based on race, ethnicity, class, and sexuality in the national story. Their histories and those of the many other women whose lives intersected with contemporary park sites defy a rosy narrative that ignores histories of conquest, empire-building, and unequal citizenship. Just as the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment offered the chance to re-examine the long struggle over voting rights in the United States, uncovering the women of the parks is a vital step to insisting that the complexity of women’s lives mirrors the complexity of the nation’s history.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.

This project was conducted in Partnership with the University of California Davis History Department through the Californian Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit, CA# P20AC00946

Footnotes

1 Betty Reid Soskin, Sign My Name to Freedom: A Memoir of a Pioneering Life (Carlsbad, CA: Hay House, 2018), 154.

2 This article focuses on the “Pacific West Region,” which includes national park sites within the eight states of California, Hawai‘i, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Washington, portions of Arizona and Montana, and the territories of Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The article is part of a larger research project focused on parks in this region, which also includes biographical sketches on diverse women whose lives intersected with contemporary National Parks located in the US West and Pacific. Some of these women are mentioned in this article. The full collection is available through the National Park Service website.

3 Kirk Savage, “History, Memory, and Monuments: An Overview of the Scholarly Literature on Commemoration,” accessed Oct 8, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/resedu/savage.htm.

4 “Interchange: Women’s Suffrage, the Nineteenth Amendment, and the Right to Vote,” Journal of American History 106: 3 (December 2019): 662-94; Liette Gidlow, “Beyond 1920: The Legacies of Woman Suffrage,” accessed Oct 8, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/articles/beyond-1920-the-legacies-of-woman-suffrage.htm.

5 For examples of the outpouring of research connected to the centennial, see Martha S. Jones, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (New York: Basic Books, 2020); Cathleen D. Cahill, Recasting the Vote: How Women of Color Transformed the Suffrage Movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020); The Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Harvard’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, The Long Nineteenth Amendment https://long19.radcliffe.harvard.edu/; “Empire Suffrage Syllabus,” Women and Social Movements https://documents.alexanderstreet.com/empire-suffrage-syllabus/home.

6 Quotation from 1872 Yellowstone National Park Protection Act; see “Origin of the National Park Idea,” https://www.nps.gov/articles/npshistory-origins.htm.

7 Anne F. Hyde, Empires, Nations, and Families: A New History of the North American West, 1800–1860 (HarperCollins, 2011), 18.

8 Margaret D. Jacobs, White Mother to a Dark Race: Settler Colonialism, Maternalism, and the Removal of Indigenous Children in the American West and Australia, 1880-1940 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009), 10-11.

9 Louise Pubols, The Father of All: The de la Guerra Family, Power, and Patriarchy in Mexican California (University of California Press, 2009).

10 Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge: Harvard, 2006).

11 For an example of US settler colonialism, see Laurel Clark Shire, Threshold of Manifest Destiny: Gender and National Expansion in Florida (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016).

12 Jean Barman and Bruce McIntyre Watson, Leaving Paradise: Indigenous Hawaiians in the Pacific Northwest, 1787–1898 (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2006); “Pineapples and Rye Grass: The Role of Hawaiian Laborers at Whitman Mission,” accessed Sep 4, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/whmi/learn/historyculture/hawaiian-laborers-at-whitman-mission.htm.

13 Marcus Whitman, as quoted in Barman and Bruce Watson, Leaving Paradise,117.

14 David Chang, The World and All the Things Upon It: Native Hawaiian Geographies of Exploration (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016).

15 Gordon H. Chang and Shelly Fisher Fishkin, eds., The Chinese and the Iron Road: Building the Transcontinental Railroad (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2019). Migrations and intermixtures of peoples led to concepts of race, gender, and class becoming malleable for a short time, as depicted in Susan Johnson, Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush (New York: Norton, 2000).

16 Robert C. Likes, Looking Back at Cerro Gordo (Pittsburgh, PA: RoseDog Books, 2010) concerns Cerro Gordo specifically, but other works address female entrepreneurial labor in early western cities, including Edith Sparks, Capital Intentions: Female Proprietors in San Francisco, 1850-1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006).

17 Brendan C. Lindsay, Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846¬–1873 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 4, 147-48.

18 Charles Camden, The Autobiography of Charles Camden (San Francisco: Camden family, 1916); Laura Christman, “The Story of Kate Camden, Native American in a Gold Rush family,” National Park Service, accessed November 8, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/whis/kate-camden.html.

19 Matthew Fox-Amato, Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019), chapter 1.

20 For Asian immigrant family labor in the West, see Cecilia M. Tsu, Garden of the World: Asian Immigrants and the Making of Agriculture in California’s Santa Clara Valley (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013). For Indigenous labor, see William J. Bauer, We Were All Like Migrant Workers Here: Work, Community, and Memory on California’s Round Valley Reservation, 1850-1941 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

21 Ana Elizabeth Rosas, Abrazando el Espíritu: Bracero Families Confront the US-Mexico Broder (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Lorena Oropeza, “Women, Gender, Migration, and Modern US Imperialism,” in Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor and Lisa G. Materson, eds., The Oxford Handbook of American Women’s and Gender History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 99–100.

22 For more information and sources, see Bracero History Archive created by the Roy Rosenzweig center for History and New Media, http://braceroarchive.org/about.

23 Rumi Yasutake, “Re-Franchising Women of Hawai‘i, 1912–1920: The Politics of Gender, Sovereignty, Race, and Rank at the Crossroads of the Pacific,” in Catherine Ceniza Choy and Judy Tzu-Chun Wu, eds., Gendering the Trans-Pacific World (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2017), 117.

24 Russell A. Apple, Pahukanilua: Homestead of John Young, Kawaihae, Kohala, Island of Hawai‘i (National Park Service, Hawaii State Office, 1978), 73, 77; George S. Kanehele, Emma: Hawaii’s Remarkable Queen, A Biography (Honolulu, Hawaii: Queen Emma Foundation, 1999), 4; Noenoe K. Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 28–30.

25 Silva, Aloha Betrayed, 178, 182–184, 187.

26 Louise Newman, White Women’s Rights: The Racial Origins of Feminism in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Allison L. Sneider, Suffragists in an Imperial Age: US Expansion and the Woman Question, 1870-1929 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

27 Patricia Grimshaw, “Settler Anxieties, Indigenous Peoples, and Women’s Suffrage in the Colonies of Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i, 1888–1902,” in Louise Edwards and Mina Roces, Women’s Suffrage in Asia: Gender, Nationalism and Democracy (Abingdon, Oxon: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), 233–34; Peggy Pascoe, Relations of Rescue: The Search for Female Moral Authority in the American West, 1874–1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

28 Sneider, Suffragists in an Imperial Age; Rebecca J. Mead, How the Vote Was Won: Woman Suffrage in the Western United States, 1868–1914 (New York: New York University Press, 2004).

29 Susan B. Anthony, Senate Committee on Woman Suffrage, Woman Suffrage: Hearings on S. J. Res. 53, 57th Cong., 1st sess., 18 February 1902, 4 as quoted in Kristin L. Hoganson, “‘As Badly off as the Filipinos’: US Women’s Suffragists and the Imperial Issue at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Journal of Women’s History 13, no. 2 (2001): 17.

30 Sneider, Suffragists in an Imperial Age.

31 For further treatment of the complex history of Native American citizenship and voting rights, see Cathleen D. Cahill, “‘Our Democracy and the American Indian’: Citizenship, Sovereignty, and the Native Vote in the 1920s,” Journal of Women's History, 32, no. 1 (2020): 41-51; and Stephen Kantrowitz, “‘Not Quite Constitutionalized’: The Meanings of ‘Civilization’ and the Limits of Native American Citizenship,” in Gregory P. Downs and Kate Masur, The World the Civil War Made (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 75–105.

32 Erika Lee, At America’s Gates: Chinese Immigration during the Exclusion Era, 1882–1943 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003).

33 Celeste Montoya, “From Seneca to Shelby: Intersectionality and Women’s Voting Rights,” in Holly J. McCammon and Lee Ann Banaszak, 100 Years of the Nineteenth Amendment: An Appraisal of Women’s Political Activism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 113-115; Rosina Lozano, “Vote Aquí,” Modern American History 2, no. 3 (2019): 394, doi:10.1017/mah.2019.31; and James Thomas Tucker, The Battle over Bilingual Ballots: Language Minorities and Political Access under the Voting Rights Act (Burlington, VT, 2009), 27.

34 For a robust conversation about the distinctions between formal and substantive citizenship, see Evelyn Nakano Glenn, Unequal Freedom: How Race and Gender Shaped American Citizenship and Labor (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004).

35 Mae M. Ngai, Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), 4, 8.

36 Tule Lake Committee, “History,” 2012, text from Barbara Takei and Judy Tachibana, Tule Lake Revisited: A Brief History and Guide to the Tule Lake Concentration Camp Site, Second Edition (Tule Lake Committee, Inc, 2012), https://www.tulelake.org/history.

37 Noenoe K. Silva, Aloha Betrayed: Native Hawaiian Resistance to American Colonialism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004); Haunani-Kay Trask, From a Native Daughter: Colonialism and Sovereignty in Hawai‘i (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1999); Cutcha Risling Baldy, We Are Dancing for You: Native Feminisms and the Revitalizations of Women’s Coming-of-Age Ceremonies (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2018); William J. Bauer, Jr., California Through Native Eyes: Reclaiming History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016).

38 LaNada Boyer, “Reflections of Alcatraz,” reprinted in Susan Lobo and Steve Talbot, editors, Native American Voices: A Reader, second edition (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2001), 517.

39 "Statement of the Third World Liberation Front Philosophy and Goals," as quoted in Karen Umemoto, “‘On Strike!’ San Francisco State College Strike, 1968–69: The Role of Asian American Students,” Amerasia Journal 15, no. 1 (1989): 3-41; Shelly Sang-Hee Lee, “Politics and Activism in Asian America in the 1960s and 1970s,” in A New History of Asian America (New York: Routledge, 2014), 291–314; Daryl Joji Maeda, Rethinking the Asian American Movement (New York: Routledge, 2012), 9-12; and William Wei, The Asian American Movement, (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993), 19-34.

40 Lorena Oropeza, ¡Raza Si! ¡Guerra No!: Chicano Protest and Patriotism during the Viet Nam War Era (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2005), chapter 5. For activism and internal colonialism, see Cherríe Moraga, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Toni Cade Bambara, eds., This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (Watertown, MA: Persephone Press, 1981); Maylei Blackwell, ¡Chicana Power!: Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2015); and Dionne Espinoza, Maria Eugenia Cotera, and Maylei Blackwell, eds., Chicana Movidas: New Narratives of Activism and Feminism in the Movement Era (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018).

41 See Dayo Gore, “Gender, Civil Rights, and the US Global Cold War,” in Ellen Hartigan-O’Connor and Lisa G. Materson, eds., The Oxford Handbook of American Women’s and Gender History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 618–37.

42 Kirk Savage, “History, Memory, and Monuments: An Overview of the Scholarly Literature on Commemoration,” accessed Oct 8, 2020, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/resedu/savage.htm.

43 National Historic Landmarks Women’s History Initiative, Progress Report, 2011–2013 (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 2013); “Telling All Americans’ Stories: Publications on Diverse and Inclusive History,” National Park Service.

44 “Hubble Trading Post National Historic Site, Ganado, Arizona,” https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/american_latino_heritage/hubbell_trading_post_national_historic_site.html