Last updated: May 22, 2023

Article

The Road to Chancellorsville

- Duration:

- 5 minutes, 12 seconds

By the winter of 1862 into 1863, the escalating pressure of two years of war was taking its toll on the fledgling Confederacy. Join Ranger Maddie to discuss how supply shortages and internal turmoil impacted the Army of Northern Virginia in the months before the Battle of Chancellorsville. This program was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.

Library of Congress

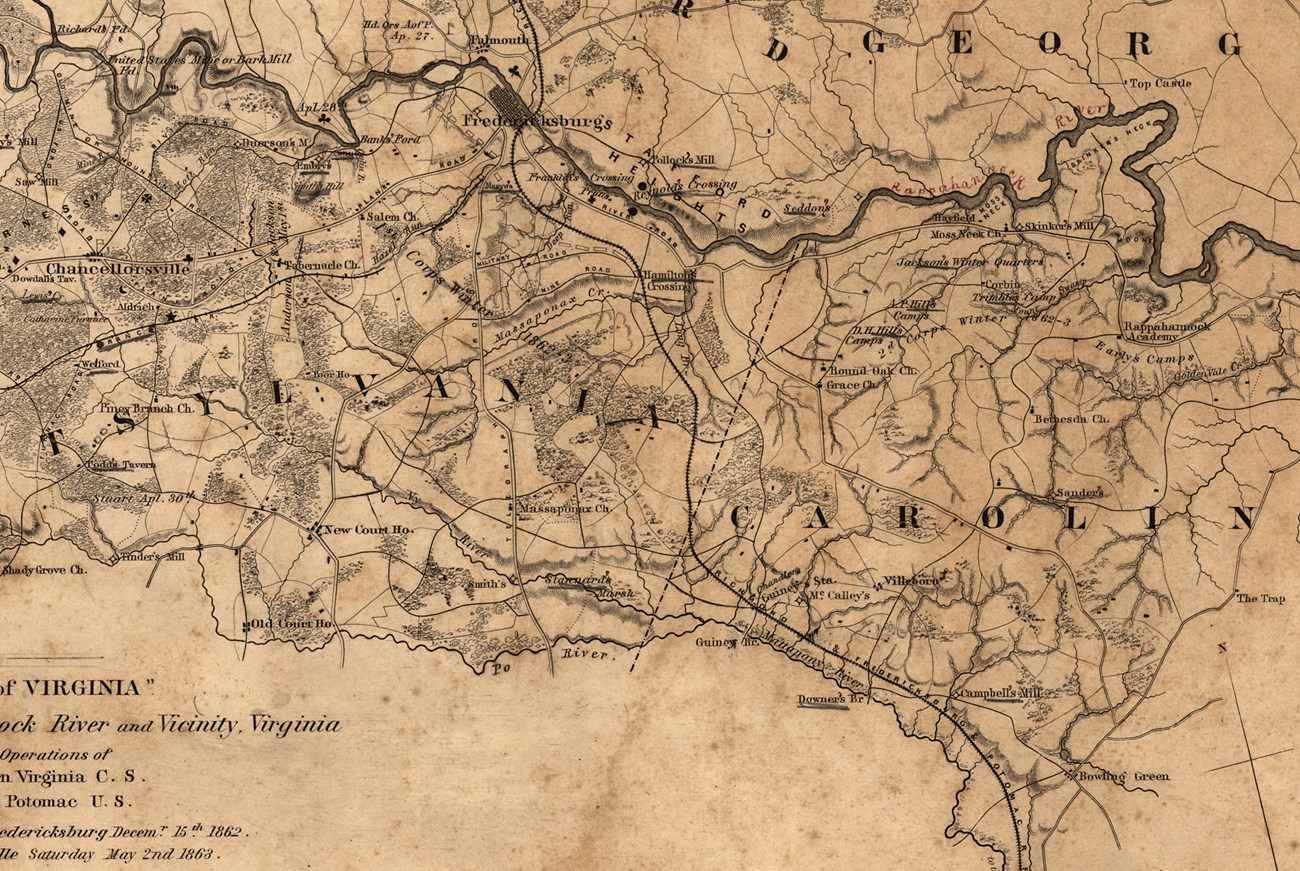

Guinea Station served as the main supply depot for Lee’s army at the time. Soldiers, as well as enslaved men impressed by the Confederate army, unloaded thousands of pounds of supplies each day and transported them to Lee’s soldiers in the field. By the spring of 1863, the state of Virginia suffered from major supply shortages. A combination of factors produced these shortages, such as a lack of agricultural production during the winter, the U.S. blockade of Southern ports, and severe inflation.

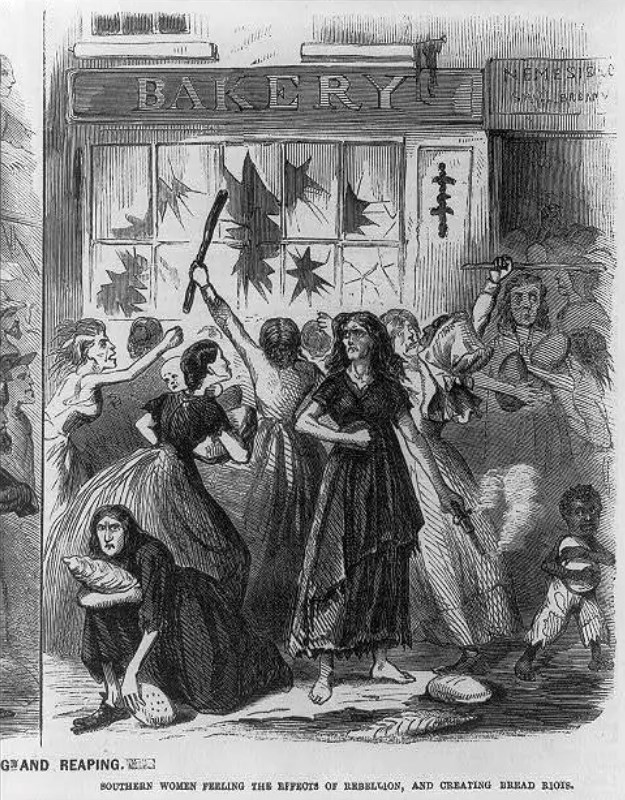

Civilians in Virginia were hit hard by food shortages, especially women left behind to support themselves. Adding more economic stress, in March of 1863, the Confederate Congress passed the Impressment Act, which authorized the government to take food, supplies, and enslaved people from civilians to support soldiers in the field.

Published in Harpers Weekly

On April 2, 1863, hundreds of women in and around Richmond took to the streets in what is known as the Richmond Bread Riot. Confederate officials arrested roughly 60 people for their involvement. The Confederate government and Southern press made a concerted effort to keep word of the riot from spreading. John Beauchamp Jones, a clerk working in the Confederate government, recorded in his diary on April 3 that “no account of yesterday’s riot appeared in the papers to-day, for obvious reasons.”1

Based on the diaries and letters of soldiers in Lee’s army, little to no information about the riot made its way into the ranks. Few Confederate soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia are known to have written about the riot. On April 2, Charles Minor Blackford of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry Regiment recorded in his diary: “Rumors of a bread riot in Richmond. Lee has enjoined the editors to say nothing about it, and of course there a thousand wild rumors.”2 Days later on April 6, William White of the Richmond Howitzers wrote, “The Richmond papers are teeming with an account of a ‘Bread Riot’ that took place there a few days since. . . . It will undoubtedly have an injurious effect upon our cause abroad and will give new impetus to our enemies.”3

In early April, most soldiers in Lee’s army wrote about daily activities, high prices, and weather, either paying no mind to news of a riot in the Confederate capitol or unaware that it took place. Private Richard Henry Brooks of the 51st Georgia Infantry Regiment wrote to his wife who was struggling to provide for herself: “you will have to do the best you can for I do not know what is best for you to do . . . I will say to you that our fair is very bad here we can Live on what we get to eat by spending about all that we make.”4 Some soldiers resorted to buying oysters from locals to make do.

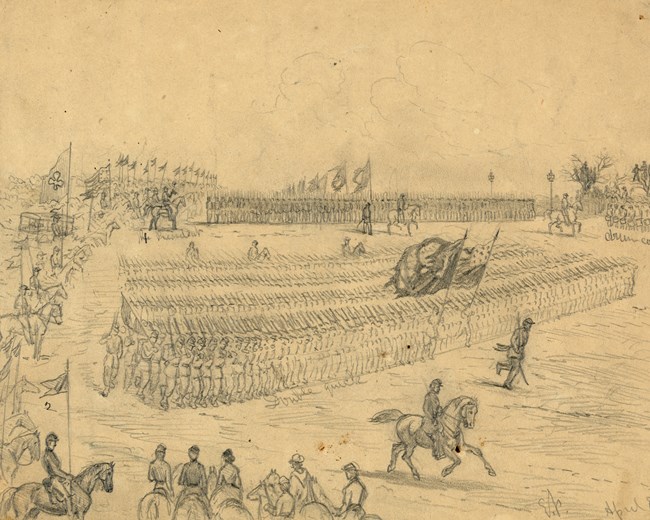

In an attempt to alleviate supply issues, General Lee sent 15,000 soldiers under General James Longstreet south to Suffolk, Virginia. Longstreet was instructed to forage for supplies and protect the Confederate capitol. In preparation for the upcoming battle, General Lee made further changes on April 15, ordering his soldiers to reduce their supplies to only what was necessary and to remove all horses that could be spared. Lee’s chief of artillery, General William Pendleton, told his troops: “General Jackson takes no trunk himself, and allows none in his corps. The clerks on Gen. Lee’s office are not mounted . . . Examples so significant may well be followed throughout the army.”5

Sketch by Alfred Waud, Library of Congress

The US Army of the Potomac, encamped in the town of Falmouth just north of Fredericksburg, quickly learned about the issues that the Confederate Army faced. Back in January 1863, General Joseph Hooker took command of the army and created a new intelligence unit, the Bureau of Military Information. During the winter, the BMI paid close attention to the state of Lee’s army and reported its findings to General Hooker. They learned that Lee had sent Longstreet south and that Confederate soldiers were underfed.

The US Army had outside help as well. The superintendent of the RF&P Railroad, Samuel Ruth, doubled as a Unionist spy. Ruth shared information about supply trains coming up from Richmond and sabotaged railroad operations whenever possible.

Using this intel, Hooker planned to cut Lee’s supply lines and maneuver around his defenses in Fredericksburg, drawing the Confederates into a battle.

Despite their victory at Fredericksburg in December, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army did not go into the Chancellorsville Campaign absent of major setbacks. While soldiers in Lee’s army suffered the negative consequences of shortages and inflation, civilians were impacted on a much larger scale. Lee’s army was left with few options in the spring of 1863.

While former Confederates remembered the battle as Lee’s “greatest victory,” the battle did not alleviate ongoing issues within the Confederacy at large. More bread riots followed later on in the war, as civilians continued to respond to policies that affected their daily lives. By considering the background events that led to the Battle of Chancellorsville, it allows us to complicate common understandings about the battle’s significance.