Last updated: October 14, 2022

Article

Piecing together the Atlantic Empire of Peter Faneuil

Invoice book, 1725-1737. Hancock family papers, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234. Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School. Accessed March 18. 2021.

As one of the largest port cities in colonial America, Boston relied on a complex economy built around various transatlantic trade networks. Local merchants played a vital role in forming these networks. These Boston merchants used their extensive business connections to exchange goods—including human cargo—that originated from ports in Britain, southern Europe, the West Indies, and North American colonies. During the 1720s and 1730s, Peter Faneuil, a prominent Boston merchant of French Huguenot descent, played a critical role in expanding that transatlantic trade in Boston. His surviving business records, including a day book and invoice book, enable historians to piece together his standing in this colonial merchant class. These surviving records indicate the wide range of items in which he dealt, and the comprehensive control he possessed over certain trade networks.

The Origins of Colonial Boston's Merchant Class

Beginning in the 1600s, financiers in Great Britain acted as the primary agents in the British Atlantic economy. They sold goods consigned from planters and merchants in British North America on commission. In return, these agents sent out manufactured goods to their colonial producers and provided them with financial services.1 By 1700, however, a significant number of merchants in New England and the Middle Colonies operated independently from London agents. They built and owned their own ships and created multilateral trade routes throughout the Atlantic. This local control over maritime trade allowed individual merchants to purchase goods on their own accounts and offer more complex financial services, such as insurance on ships and cargoes.2

Merchants in Boston emerged as independent entrepreneurs as early as the 1680s. Using the sale of fish, lumber, and other provisions, they grew a large shipbuilding industry.3 In particular, the sale of dried cod fish as a bulk staple good provided prominent merchants with a large amount of liquid assets that they used to purchase valuable imported foodstuffs and manufactured items in demand in New England. Merchants, in turn, stimulated the agricultural sector of the local economy by trading manufactured goods for grain and livestock. This relationship enabled the merchant class of New England to dominate all commercial activities in the region.4

Invoice book, 1725-1737. Hancock family papers, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234. Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School. Accessed March 18. 2021.

Peter Faneuil: the King of the Merchant Princes

Peter Faneuil emerged as one of the most well-known and successful merchants in colonial-era Boston. He initially worked in maritime trade under the guidance of his uncle, Andrew Faneuil. Slowly, Peter Faneuil began to trade on his own accounts and make his own profits. As a descendent of Huguenot merchants based in the port of La Rochelle, France and other ports in Europe, Peter Faneuil used close business connections in England and Holland to capitalize on the expansion of Anglo-American trade throughout the Atlantic.5 After his uncle Andrew’s death in 1738, Peter Faneuil inherited the bulk of his uncle's wealth and became perhaps the wealthiest merchant in Boston.

An invoice book containing records of merchandise imported by Faneuil between July 15, 1725 and April 21, 1737 outlines the wide range of commodities that he traded. Invoices of shipments traveling from London, Rotterdam, and other large cities in Europe, document Faneuil’s purchases of fabrics, pottery, and other manufactured items. His transactions with merchants from ports in the West Indies, namely Cape Francois, Martinique, Guadeloupe, Eustatius, Antigua, St. Allouse, and St. Lucia, included the produce of enslaved labor, namely molasses, rum, sugar, dry goods, and other high-value staple goods like cocoa. In addition to these shipments of manufactured items from Europe and bulk staple goods from the West Indies, Faneuil also imported a variety of foodstuffs (flour, salt, grain, wheat, pork, duck, bread) and provisions from locations in the Middle Colonies, such as New York, Philadelphia, and Maryland.6 His business activities reflect Boston’s role within the Atlantic: a central clearing-house of transatlantic trade.

Daybook (accounts), 1731-1796 (bulk 1731-1732). Hancock family papers, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234. Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School.

In addition, a day book documenting accounts and transactions made by Faneuil between March 7, 1731 and December 6, 1732 further illustrates the broad scope of his business activities. Containing references to many invoices of merchandise shipped and consigned to Peter and his brother Andrew Faneuil, the daybook listed many of the same goods and locations found in the invoice book. The book also listed many prominent merchants, ship masters, and customers who participated in these transactions, including Ebenezar Storer, a wholesale Boston merchant who founded a firm that sold textiles, and Alice Quick, a local retail shopkeeper.7 Along with presenting the wide range of commodities that he purchased, this daybook outlines how Faneuil financed the transportation of these goods himself, as evident by expenses such as crew wages, portenage, and wharfage listed in a number of entries. These records, therefore, depict the control that Faneuil possessed over various trade networks that was independent of British financiers.8

Faneuil’s expansive business endeavors also included various connections to the transatlantic slave trade. As illustrated in the invoice book, he engaged in trade with a number of ports for goods mostly produced by a mass labor force of enslaved individuals, mainly rum, sugar, and molasses from the West Indies. Faneuil, in return, often supplied these colonies with foodstuffs and provisions needed to sustain these immensely profitable staple industries, such as dried fish and timber. His daybook also exhibited Faneuil’s business connections to merchants based in English port cities, such as London, that exported large quantities of enslaved Africans to colonies throughout British North America and the West Indies.9

Invoice book, 1725-1737. Hancock family papers, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234. Baker Library Special Collections, Harvard Business School. Accessed March 18. 2021.

In addition, Faneuil’s career as a merchant corresponded with a period in which almost all industries within Boston’s urban economy expanded their use of slave labor to varying degrees, with the number of enslaved individuals in Boston increasing from roughly 3 to 10 percent of the total population between 1720 and 1740.10 This expansion of slavery in colonial-era Massachusetts occurred during an increase in economic activity within the region overall, in which Faneuil and other merchants played integral roles in stimulating the growth of local industries through an assortment of maritime trade networks. His business records, therefore, underscore the centrality of the transatlantic slave trade to his exploits as one of the most prominent merchants in the colony.

The Legacy Today

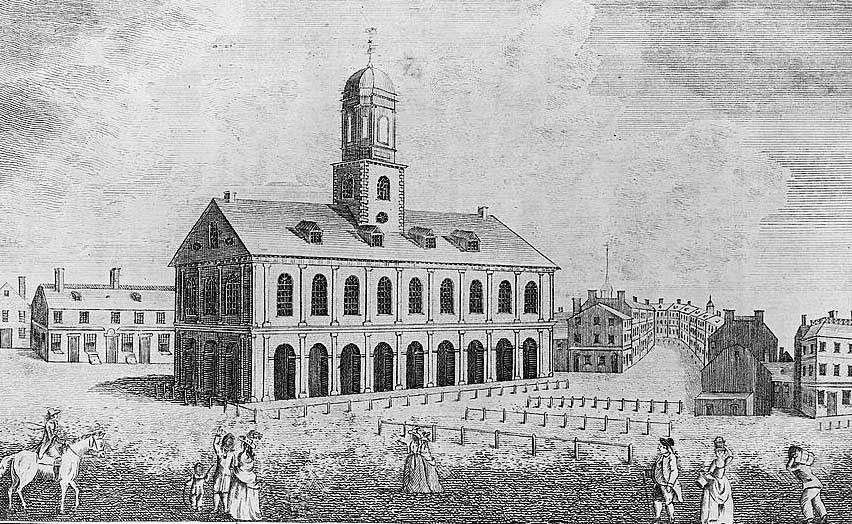

Following the death of his uncle, Andrew, Peter Faneuil worked alongside other leading merchants in Boston to introduce fixed, regulated marketplaces to the town. In 1740 and 41, Faneuil sought to achieve this goal by personally funding the construction of a new public marketplace. The completion of this project in 1742 became the original structure of today's Faneuil Hall.11 This new marketplace supplemented traditional marketing practices by providing a more centralized space for tradesmen to sell their goods. Faneuil and other merchants’ efforts to organize commercial life in Boston were some of the most decisive factors in developing the city as a center of production, exchange, and consumption.12

In eighteenth-century Boston a number of merchants helped organize and stimulate the regional economy through their individual efforts to expand transatlantic trade networks tied to the port. Peter Faneuil’s financial records demonstrate his status as a member of the mercantile class that organized commercial life in New England through their documentation of the wide variety of goods Faneuil imported and exported and his extensive control within specific trade networks. Therefore, these business papers offer a useful lens for which to view the development of transatlantic maritime trade in colonial-era Boston.

Footnotes

- R.C. Nash, “The Organization of Trade and Finance in the British Atlantic Economy, 1600-1830,” in The Atlantic Economy During the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Organization, Operation, Practice, and Personnel, ed. by Peter A. Coclanis (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 98.

- Stephen J. Hornsby, British Atlantic, American Frontier: Spaces of Power in Early Modern British America (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2005), 194-195.

- Nash, “The Organization of Trade and Finance in the British Atlantic Economy, 1600-1830,” 102-103, 108-109.

- British Atlantic, American Frontier, 135.

- J.F. Bosher, “Huguenot Merchants and the Protestant International in the Seventeenth Century,” William and Mary Quarterly 52, no. 1 (1995): 78, 90-93.

- Hancock family, Hancock family papers, 1664-1854 (inclusive), Peter Faneuil papers 1716-1739, invoice book, 1725-1729, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234, Volume F-3, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School, https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HBS.Baker.GEN:27257254-2016, seq. 60-95.

- Ebenezer Storer & Son records 1763-1788 (inclusive),” Colonial North America at Harvard Library, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Harvard University, https://colonialnorthamerica.library.harvard.edu/spotlight/cna/catalog/990147138070203941; Jacqueline Baker Carr, “Marketing Gentility: Boston's Businesswomen, 1780-1830,” The New England Quarterly 82, no. 1 (2009): 29.

- Hancock family, Hancock family papers, 1664-1854 (inclusive), Peter Faneuil papers 1716-1739, invoice book, 1725-1729, Mss:766 1712-1854 H234, Volume F-3, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School. https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HBS.Baker.GEN:27257254-2016, 71-133.

- Hornsby, British Atlantic, American Frontier, 50-54.

- Robert E. Desrochers Jr, “Slave-for-Sale Advertisements and Slavery in Massachusetts, 1704-1781,” The William and Mary Quarterly 55, no. 3 (2002): 643-644.

- Jonathan M. Beagle, “Remembering Peter Faneuil: Yankees, Huguenots, and Ethnicity in Boston, 1743-1900,” New England Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002): 393-395.

- Kenneth Morgan, “Port Location and Development in the British Atlantic World in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries,” in The Sea in History-The Early Modern World, ed. by Christian Buchet and Gérard Le Bouedec (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer, 2017), 166-167.