Last updated: March 26, 2021

Article

Dr. McLoughlin's Garden

NPS Photo / Troy Wayrynen

The fertile soils of the Pacific Northwest that nurtured edible bulbs, berries, and tobacco cultivated by Indigenous peoples, also nourished seeds and plants from Britain and other far away places around the globe. The garden planted by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) at Fort Vancouver provided nutrition, medicinal remedies, and an emotional connection to employees' homes in the British Isles. Even as the garden impressed both locals and visitors with the power of the British Empire, it also provided for them in the form of seeds and cuttings offered by Chief Factor Dr. John McLoughlin.

The Garden Grows in Significance

The first references to a garden at Fort Vancouver were made in 1828. Referred to as "extensive," by HBC Governor George Simpson and including "some small apple trees and vines," according to American explorer Jedediah Smith, the size and location of the garden at that time is not documented. By the mid-1830s, the garden - located on the north side of the fort's stockade - was estimated to be five acres, and Company officers were enjoying apples, peaches, grapes, melons, and many variety of vegetables. Flowers from the garden decorated Dr. McLoughlin's dinner table. The garden was also an experimental nursery, containing seeds and plants from locales around the world: dahlias (grown in glass frames) and acacia from Hawai'i, peaches from South America, and seeds and possibly apricot, plumb, pear and cherry trees from the Royal Horticultural Society in Britain. Evidence is contradictory, but oranges and lemons may have been grown, possibly protected in greenhouses during the cold winters.

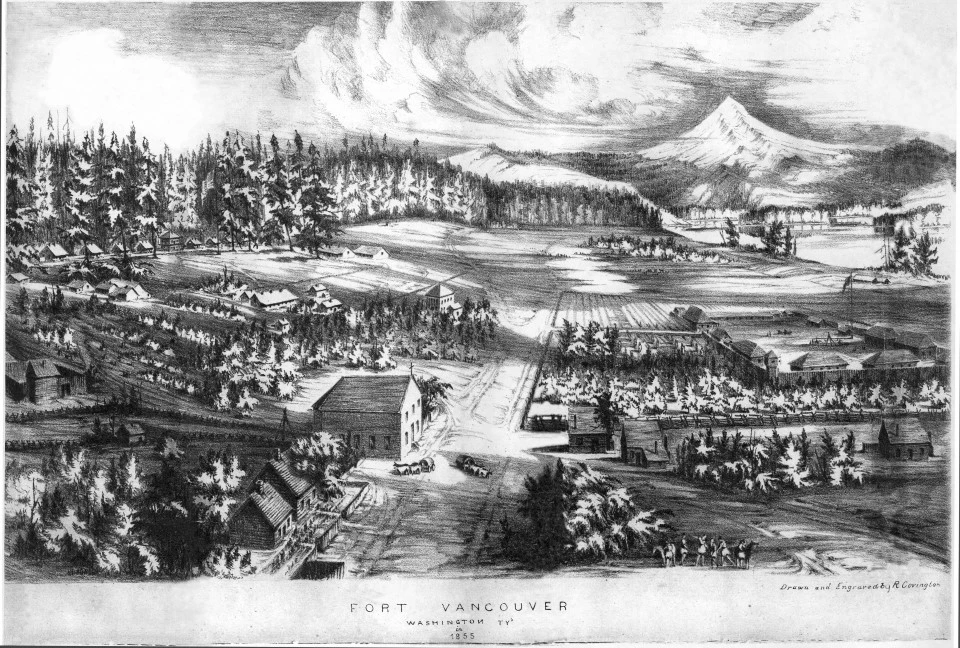

The scientifically and socially significant space eventually spread to more than eight acres, and just as at other gardens in Britain at the time, access to the garden was by invitation only, in this case by Dr. McLoughlin. Several visitors commented on the enjoyable hours spent strolling the 20 to 30 foot wide walks. A summerhouse, located on the northern edge, functioned as a shady respite in the summer and possibly a greenhouse in the winter. This painting in the Yale University Library collection shows a view to the southwest, with the Columbia River behind the fort Vancouver stockade, and a lone rider on Upper Mill Road (now East 5th Street). Dr. McLoughlin's garden can be seen between Upper Mill Road and the fort stockade, and west (right) of the stockade entrance road. The summerhouse is at the northern edge of the garden, just to the left of the large, dark building with a hipped roof.

Other than the head gardener, William Bruce, little is known about those who labored in the garden beyond names in the list of employees. Planting and harvesting was done by men, while weeding was a job assigned to women and boys. According to Eloisa McLoughlin, daughter of Dr. McLoughlin and his wife Marguerite, the head gardener previous to Mr. Bruce had been an "Indian." This is not surprising as generally about one-third of the Fort Vancouver work force was comprised of American Indians from nearby tribes.

While HBC employees and local American Indians labored in the garden, its bounty was not meant for them. The HBC used access to certain foods as a tool to reinforce the higher status of officers and their families, just as many cultural groups have done for centuries. The food produced in the garden, and the privilege of enjoying its pleasant surroundings, was enjoyed only by a select group of people living at Fort Vancouver, along with visitors Dr. McLoughlin chose to invite. This presents an interesting paradox. According to kitchen garden practice at the time, two acres would have provided those few people with ample food both during the growing season and through the long winter. Why, then, did the garden quickly grow to more than eight acres in size? This was one of several questions that were included in the research design for an archaeology project conducted by the National Park Service during the field seasons of 2005 and 2006.

Decline and Long-Term Effects

Gold was discovered in California in 1848, creating a constant shortage of laborers at Fort Vancouver. This undoubtedly effected agricultural activities, as did the boundary decision of 1846, which placed the boundary between Great Britain and the United States at the 49th parallel. Though they received official permission to continue business operations, Fort Vancouver sat well into American territory. Two significant things occurred: the HBC moved its administrative functions from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island, and the US Army arrived at the site in 1849. Initially, relations between the HBC and the Army were guardedly pleasant, and 70% of the garden was leased by the HBC to the Army in 1852. However, the HBC's activities and influence in the region continued to wane. In 1858, Army recruits devastated both the garden and the orchard to the west of the HBC fort stockade. In 1860, the HBC moved all operations to Fort Victoria, abandoning Fort Vancouver completely.

The effects of the HBC's agricultural operations in the region included the first introduction of non-native species in the Northwest as agricultural crops from Europe and "stowaway" seeds brought with ships' cargo. Agricultural activities allowed more people to live successfully in the area, but also brought exotic plant species to compete with the native flora.

The Garden Today

In the 1960s, the National Park Service began reconstructing the HBC's Fort Vancouver. This reconstruction includes smaller-scale replicas of the fort's garden and orchards. Today, the Garden at Fort Vancouver is maintained by a hardworking team of volunteer gardeners and national park staff. The Fort Vancouver Garden is a wonderful place to visit year-round. Learn more about visiting the Garden here.

NPS Photo / Junelle Lawry