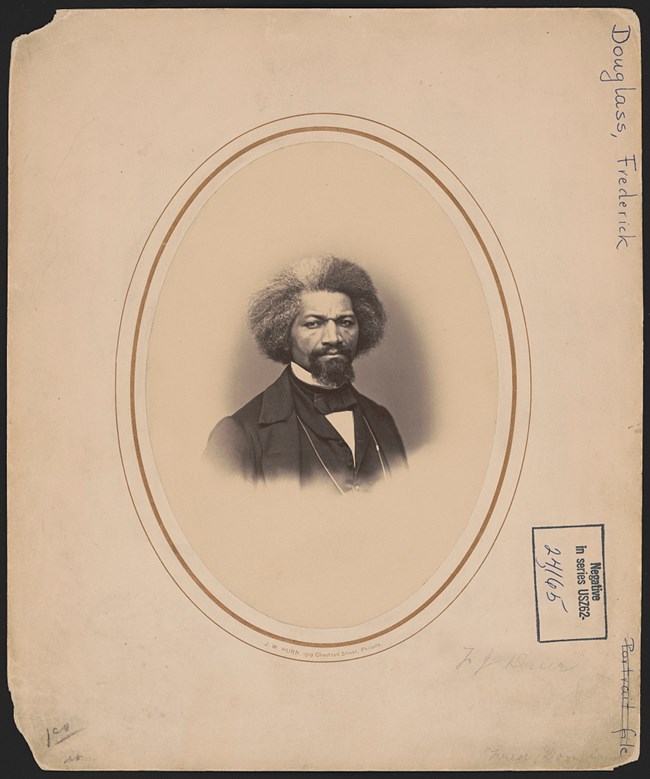

Library of Congress The following is an exerpt from a letter sent by Frederick Douglass to a friend in Leeds, England, dated Dec. 29th, 1863. “I never was listened to with such attention as now. My leading idea now before the people is, “No war but an abolition war; no peace but an abolition peace.” The government and people still need line upon line, and precept upon precept. At Washington, a few evenings ago, where I went to deliver two lectures in aid of the contrabands or freedmen, and where I raised more than one hundred dollars for them, the house was densely packed with white and coloured people, and the papers say that two thousand went away unable to gain admission. Now, think of me in Washington, where three years ago, I should have been murdered in ten minutes had I dared to open my mouth for my enslaved people. While in Washington I was taken by Mr. James Wormley over to the Virginia side, to visit the contraband villages on the estate of the rebel General Lee, known as Arlington Heights. All around were striking proofs of retribution. Here we see the proud mansion of the rebel slaveholder occupied by common soldiers and by his former slaves; his fences in ruins; his noble ancestral trees, the pride of generations, cut down; his once beautifully winding lane, over which he rolled in pride and splendour, all cut up by the wheels of army wagons; his formerly richly furnished parlours are now occupied by soldiers, and the whole premises bear marks of desolation. I should have been deeply sad over the ruin but for the thought that this was the reward of iniquity—a righteous retribution—a wise and necessary chastisement of crimes unrepented, perpetrated against the weak, the ignorant, and the defenseless. I went to the gentlemen’s ‘Smoke House,’ there I saw dear little children, some of them nearly white, and possibly more nearly related to the General than he would be willing to own. They were too small to be taken south in his flight, and had been left on the place with a few old slaves, who were too old to be taken, and not wanted. The little children in the “Smoke House” were being taught to read. The “Smoke House” had become the school house, and the property of the pupils. Taking a book in my hand, I said to one little fellow, “Can you spell where your book is opened?” “Yes, sir,” he answered. I pronounced ‘abandon,’ which was the first word in the column. He spelt it off with such ease. Had the past participle been added, the word might be the crying word of the slave system at Arlington Heights. I tried to make a few encouraging remarks to these dear little children and their teachers, and left for the ‘freedmen’s village,’ about a mile from the mansion of General Lee, situated on the south part of this plantation. This place is the temporary home for slave women, children, and old slaves, who were abandoned and deserted by their masters on the approach of the loyal army. Others, too, are here who have made good their escape, after having endured untold hardships and perils in their efforts to reach our lines. More than a thousand here have thus gained their freedom and are beginning life with nothing but the few rags upon their persons with which they made their escape. Of course they are in great destitution; much has been done for them, but they need much more. Regular religious exercises are held among them every Sunday, and now they have a day school establish, from which much good may be expected. I wish you could see this school. When I was there there were a hundred children in it, the descendants of slaves, who held for many generations, going back more than two hundred years. The sight of these poor little children brought tears of joy, sadness, hope, and fear, and I know not what else. Three years ago to have taught these children in Virginia would have subjected the teacher to a heavy fine and to imprisonment. Now teachers and pupils are alike safe. I thought and felt much as I looked upon and listened to those black children. I thought of the generations of the race which had preceded them, sent from time to eternity in the dark, and not even allowed to learn to read the name of Heaven; I thought how much further these children might have been advanced had their ancestors enjoyed the privileges now opening (Heaven grant that they be not shut) before them. The teachers (Mr. and Mrs. Simmons) kindly asked me to address the children. I complied, and sang two or three hymns with them. I enjoyed the interview more than I can express, and am soon to visit them again, also those at Alexandria. But I am filling my letter with “contrabands,” and indeed I might write a volume about them, if I had time, and you required it to deepen your interest in my long-enslaved people." Source: Printed in the Leeds Mercury, January 21, 1864 |

Last updated: February 14, 2021