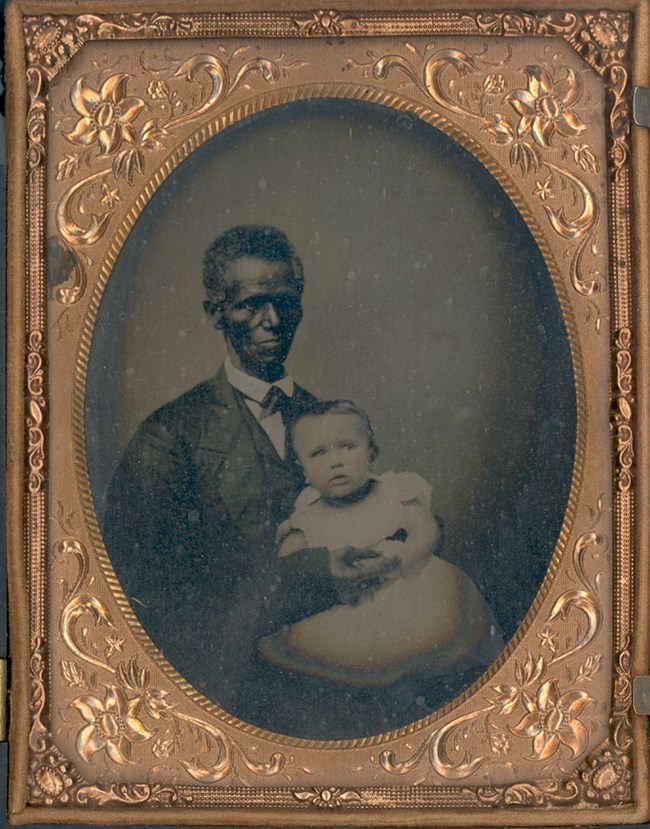

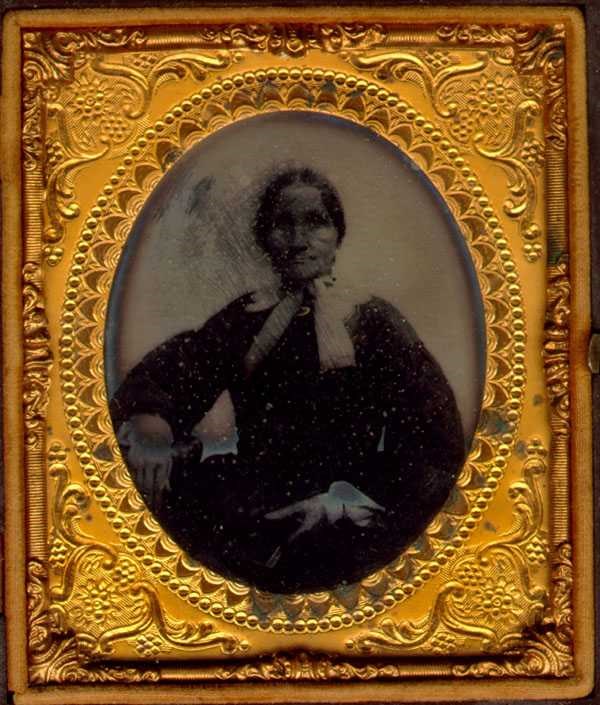

NPS Maria Syphax was the daughter of an enslaved woman named Arianna Carter, and George Washington Parke Custis who was born in 1803 at an undetermined location. This may have been at Mount Vernon where Carter may have been enslaved, Arlington Plantation, or somewhere else. Maria may not have been Custis’s only child from an enslaved woman, but she seemed to receive special, paternal attention from him.

In 1821, Custis permitted her to marry Charles Syphax, an enslaved house servant, in the parlor of Arlington House, ten years before Custis’s white daughter, Mary, would wed Lt. Robert E. Lee in the same room. Charles Syphax was the son of a free black itinerant Alexandria street preacher and an enslaved woman from Mount Vernon. He was enslaved at the Mount Vernon estate and was transferred to Arlington House when Martha Washington died, one of fifty-seven enslaved people who came to Arlington from Mount Vernon with George Washington Parke Custis in 1802. He was about 9 years old. The enslaved people owned by the Custis family ended up moving not only to Arlington House, but also Tudor Place and Woodlawn. The separation at Mount Vernon was a heart-wrenching time; enslaved people who were emancipated in George Washington’s will were separated sometimes from family and friends who were enslaved to Martha Washington’s estate – the majority of the people enslaved at Mount Vernon. At Arlington House, Charles Syphax oversaw the dining room and was the unofficial leader of the Arlington enslaved community.

Custis permitting Maria and Charles to marry was not unusual. Many slaveholders allowed it though it was not legally recognized. Marriage between enslaved individuals was not explicitly prohibited by law, but they did not receive any legal recognition because the individuals were considered property. The slaveholder still retained ultimate control of the individuals, and their relationship, and could, at any moment, separate them by selling one or both away. They also benefited from the ‘increase’, or the children that were born to enslaved individuals. In some cases, these weddings included the vow, “until death or distance do you part.”

After Maria and Charles were married, they were forced to continue working in the house, Charles in the dining room, and Maria as maid to her half-sister Mary Custis and had two children during their first years of marriage. In 1825, Custis sold Maria and the children, but not Charles, to Edward Stabler, a Quaker apothecary in Alexandria. Being a Quaker, Stabler was against slavery and often purchased enslaved individuals to free them, and it is assumed Stabler freed Maria and her two children, but it does not appear on record until 1845, twenty years later.

NPS Soon after gaining her freedom, Maria acquired seventeen acres on the southwest portion of Custis’ Arlington property to live on as a free person. She and Charles had eight more children, all born free since a child’s condition of servitude was dependent on the mother. Charles Syphax would remain enslaved until December 29, 1862, when the terms of Custis’ 1857 will stated all of the Arlington enslaved people were to be freed.

In 1863, a Freedman’s Village was established on the grounds of Arlington. Over a thousand recently emancipated people settled on the property. Maria and her family were involved in the activities of the Freedman’s Village, teaching skills such as sewing, and acting as advocates on behalf of individuals to petition the government for assistance. Freedman’s Village was closed and its' residents were required to evacuate before 1900.

In 1863, tax laws were changed in part to raise money to support the expanding Civil War. Local jurisdictions had the ability to establish to craft the local tax law and mandated that taxes be paid in person by the legal owner of the property being taxed. Mary Anna Lee attempted to pay the tax through a surrgoate, but was rebuffed because she did not appear in person. The Custis property was confiscated. Along with that action the 17-acre Syphax property also was confiscated because they had no proof or ownership. Maria’s eldest son, William, used relationships he had built working as a messenger in the Interior Department. He wrote an argument defending the rights of his mother to ownership of the property that was given to her by her father even though there was no definitive documentation to prove the gift occurred. William Syphax used his connections within the government to get a bill introduced in Congress, the “Bill for the Relief of Maria Syphax.” On May 18, 1866, Sen. Ira Harris (R-NY) explained to the Committee on Private Lands Claims that it was for a woman who had once been enslaved by George Washington Parke Custis. The bill was voted on, passed, and signed by President Andrew Johnson. The property was returned to Maria Syphax. Sen. Harris later told The Congressional Globe that the committee’s decision had been “just.” Syphax property ownership was reaffirmed by Congress in 1884 during a period when the Lee descendants sued the Federal government for inappropriately confiscating the 1,100-acre property that was inherited by Mary Lee from her father prior to the war.

Maria Syphax died in 1886 leaving the 17 acres to be divided among the surviving children. Families grew and with the exception of Ennis Syphax dispersed into the wider Washington, DC, area and beyond. In 1944, the 17 acres were condemned and for the second time the remaining Syphaxes were expelled from the property they were given by George Washington Parke Custis and returned by Congress.

Maria Syphax’s story is one of perseverance and dedication. It is forever intertwined in the history of the Arlington plantation. In addition, the legacy the Syphax family continues to be felt today. Maria Syphax’s son William was appointed the first chairman of the DC Board of Trustees of Colored Public Schools and established Dunbar High School, the first black high school in the District of Columbia; and his brother John Syphax served as justice of the peace of the Arlington Magisterial Board and later was elected delegate to the Virginia General Assembly. Over the years, dozens of Syphax descendants have served honorably in the military, many attended and taught at Howard University and other prestigious universities, been elected to congress and advocated for social justice reform. |

Last updated: August 19, 2025